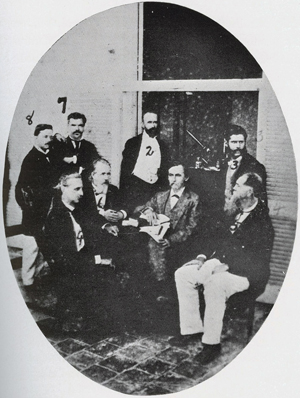

The Havana Yellow Fever Commission of the United States National Board of Health. This photograph was taken at the Commission’s laboratory in Havana’s Hotel San Carlos in August 1879. (Left to Right) Abraham Morejon, Assistant Medical Clerk; Colonel Thomas S. Hardee, Sanitary Engineer; Rudolph Matas, Medical Clerk; Henry C. Hall, U.S. Consul General at Havana; George M. Sternberg, Bacteriologist; Stanford E. Chaille, Chairman; Juan Guiteras y Gener, Pathologist; Daniel Burgess, U.S. Sanitary and Quarantine Inspector at Havana. Photograph taken from: Finlay, Carlos Eduardo. Carlos Finlay and Yellow Fever. New York: Oxford University Press, 1940. pg. 55.

In the decades leading up to the formation of the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission, revolutionary developments in science and medicine would lay a foundation for the Commission’s groundbreaking work. The rise of the germ theory of disease spurred important investigations into the biological causes of yellow fever and improvements in research methodologies would yield increasingly accurate data about the nature of the disease. While the U.S. Army Commission has been rightfully recognized for their role in proving that mosquitoes were the vector for yellow fever, their experiments would not have been possible without the insights of other pioneers working at the end of the 19th century.

The most significant discoveries of that era can be traced to the work of the Havana Yellow Fever Commission. This Commission was created in 1879 by the U.S. National Board of Health to study yellow fever in Cuba and to suggest methods for preventing the disease’s spread from the island. [1] Investigations of the 1878 Mississippi River Valley epidemic led the National Board to believe that the source of the outbreak, like so many others of that century, was Cuba. By studying the disease at its presumed source and understanding how it spread, the Board hoped it could help prevent future yellow fever epidemics in the United States. [2]

The National Board recruited George Miller Sternberg of the U.S. Army, Stanford E. Chaillé of Tulane University, Juan Guitéras y Gener (Juan Guiteras) of Cuba, and T.S. Hardie of New Orleans to serve on the Havana Commission. With the full approval of the Spanish government in Cuba, the Commission conducted epidemiological and scientific investigations on the island in the Summer of 1879. The American delegation also worked closely with another commission that the Spanish government had created for the express purpose of aiding the U.S.-led group and continuing its work after the Americans returned to the United States. [3]

Photomicrograph of the blood of a fatal case of yellow fever. From: Sternberg, George Miller, and Tayloe Gwathmey. Photomicrographs From Negatives of Yellow Fever Studies : Made In Havana for the Havana Commission for Investigation of Yellow Fever by Order of the National Board of Health. Havana: circa 1879.

The U.S. and Spanish Commissions did not discover the cause of yellow fever or how it was spread, but they did gather substantial data about the disease. Their scientific studies yielded new insights about the effects of yellow fever on the human body and confirmed that it does not affect most other species in the same way as it does humans. [4] Meanwhile, their epidemiological studies improved the scientific community’s understanding of the conditions in which yellow fever thrives.

The Havana Yellow Fever Commission Advises Quarantine and Sanitation

Based on their experimental and epidemiological data, the Havana Commission recommended improvements for the U.S. quarantine system and advised the development of an extensive sanitation program in Cuba to prevent the spread of yellow fever. While the quarantine recommendations were generally sound, the call for sanitation improvements was founded on an unverified assumption about the transmission of yellow fever. While the Commission admitted that “the whole truth has certainly not been fathomed” about the causes of yellow fever, they argued that there were significant correlations between the presence of unsanitary conditions and the prevalence of yellow fever in Cuba. [5] They incorrectly assumed that the elimination of these conditions through a large-scale public health program would likely halt the spread of yellow fever. This point was forcefully made in the Havana Commission’s report to the National Board of Health:

The people must be provided with means to become intelligent, enlightened, especially in hygiene, prosperous, and sufficiently numerous to eventually gain both the knowledge and the power necessary to correct their insanitary evils. This is not only the best, but the only means. Until their accomplishment (which the present generation will not live to witness) Havana will continue to be a source of constant danger to every vessel within its harbor, and to every southern port which these vessels may sail to during the warm season. [6]

Members of both the U.S. and Spanish commissions would continue their work after 1879 and emerge as important figures in yellow fever research. George Miller Sternberg, who was responsible for much of the biomedical research conducted by the U.S. commission, built upon his 1879 studies and continued the hunt for a biological cause of yellow fever. [7] At the same time in Cuba, a relatively-unknown physician from the Spanish commission, pursuing the vector for yellow fever, would recognize the critical link between yellow fever and the mosquito.

Carlos Finlay’s Mosquito Theory and Yellow Fever

Carlos J. Finlay and his wife, Adele (Shine) Finlay, in the late 1860s. From: Finlay, Carlos Eduardo. Carlos Finlay and Yellow Fever. New York: Oxford University Press, 1940. p. 19.

Carlos J. Finlay, a prominent Cuban physician who had served on Spain’s 1879 yellow fever commission, identified the link between yellow fever and the Aedes Aegypti mosquito long before the idea would become widely accepted in the world scientific community.

Finlay first recognized that mosquitoes may be the vector for yellow fever after studying the work of George Miller Sternberg. While serving on the Havana Yellow Fever Commission, Sternberg employed new technologies to capture microscopic images of blood extracted from yellow fever patients as they experienced the different stages of the disease. Finlay inferred from the Sternberg images, his own scientific research about mosquitoes, and a wealth of existing epidemiological data that three conditions were necessary for the spread of yellow fever:

1. The existence of a yellow fever patient into whose capillaries the mosquito is able to drive its sting and to impregnate it with the virulent particles, at an appropriate stage of the disease.

2. That the life of the mosquito be spared after its bite upon the patient until it has a chance of biting the person in whom the disease is to be reproduced.

3. The coincidence that some of the persons whom the same mosquito happens to bite thereafter shall be susceptible of contracting the disease. [8]

When Finlay presented his mosquito theory at an 1881 meeting of the Academia de Ciencias Médicas, Físicas y Naturales de la Habana, the global scientific community generally dismissed it. Few other scientists of the period were proposing that mosquitoes could spread disease and, as Finlay himself acknowledged in his presentation:

I understand too well that nothing less than an absolutely incontrovertible demonstration will be required before the generality of my colleagues accept a theory so entirely at variance with the ideas which have until now prevailed about yellow fever. [9]

From 1881 to 1900, Finlay pursued a campaign of experimental inoculations on human volunteers, with the aim of demonstrating both the truth of his hypothesis and the possibility of inducing immunity to the disease. Finlay believed that he had produced cases of yellow fever by mosquito inoculation, although the larger public health community remained skeptical. [10] George Miller Sternberg offered an essential critique of Finlay’s experiments: that the participants were never sufficiently isolated from the general population to eliminate the possibility of contracting fevers from sources other than Finlay’s mosquitoes. [11] This and the inconsistency with which fevers developed in the experimental participants kept the mosquito theory on the margins of medical research until political developments on the international stage would compel others to take it up.

”Sources“