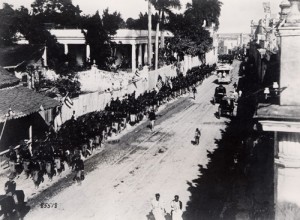

Soon after taking control, the occupation government used its powers to implement a massive public health program aimed at the eradication of yellow fever in Cuba. It passed strict sanitation and quarantine regulations, organized local street-sweeping forces, hired Cuban health inspectors, constructed hospitals, built sanitation systems, published public health reports in newspapers, and stationed non-immune U.S. soldiers in bases outside of the cities. [2] Leading medical authorities in the United States argued that yellow fever was most likely spread through fomites–objects infected by the blood and/or excrement of yellow fever victims. Although this theory had not been scientifically proven, the occupation government believed that through a strict sanitation and inspection system they could prevent the handling of fomites and stop the spread of yellow fever. [3]

By the summer of 1900, it was clear that the U.S. sanitation and inspection program had failed to control yellow fever in Cuba. In other ways the program had been a success. It enjoyed the support of much of the Cuban population and facilitated the decline of several other infectious diseases. [4] Initially, there was a significant decline in the yellow fever infection rate, but in 1900 the infection rate climbed again as the United States encouraged thousands of non-immune Spaniards to emigrate to Cuba and help rebuild the island. [5] Frustrated by the occupation government’s inability to control yellow fever, the U.S. Army wanted to gather more data about yellow fever in Cuba and ordered the formation of a new military commission charged with “pursuing scientific investigations with reference to the infectious diseases prevalent on the Island of Cuba.” [6]

”Sources“

[1] In her study on the relationship between yellow fever and Cuban independence, Mariola Espinosa argued that the U.S. Army occupation government’s efforts to control yellow fever in Cuba were largely motivated by a concern about the spread of the disease to the United States. See Espinosa, Mariola.

Epidemic invasions: and the limits of Cuban independence, 1878-1930. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009. This argument is in part supported by reports made by U.S. officials in Cuba. In 1899, officials introduced their annual report on sanitation in Havana with the following statements: “For a century Havana has been permitted to exist as a focus of yellow fever and a continuing menace to the rest of the world–in particular to the southern coasts of the United States–as a possible source of infection from epidemic disease involving enormous losses in lives and commercial interests. One of the most important results hoped for from the occupation of the Island by the American forces was therefore the sanitation of the city, both as a measure of safety to those who would be required to live in it, and as a mitigation of the dangers attendant upon the frequent interchange of shipments and passengers between Havana and other

ports; and it was doubtless with this object in view that the President’s order appointing a Military Governor for Havana imposed, among other serious requirements, the special duty and responsibility of its sanitation.” See Ludlow, William. (1899). “Annual report of the Department of Havana and Military Governorship of Havana, December 22, 1898 to June 30, 1899.” In

Annual Report of Major General John R. Brooke, U.S. Army, Commanding the Division of Cuba. Havana: United States Government.

p. 34

[2] Mariola Espinosa examined U.S. efforts to fight yellow fever in Cuba before 1901 in chapter 3 of Espinosa, Mariola.

Epidemic invasions: and the limits of Cuban independence, 1878-1930. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

[3] The occupation government recognized that the causes of yellow fever were unknown, but officials were nevertheless hopeful about their sanitation measures. In a report on the sanitation initiative in

Havana, officials in 1899 wrote: “It is distinctly recognized that for the future welfare of the city [Havana], the adoption, after full study and investigation, of a complete

sewer system, the rectification and adjustment of street grades, and the

paving of the city with [smooth, hard] impermeable pavements, are imperative, but pending the practicability of inaugurating these measures, it was of interest to determine to what extent the general health and death rate of the city could be favorably modified by the thorough cleansing and

disinfection of every accessible portion, public or private. The deep-seated sources of infection may not be reached by these means, and the habitat of yellow fever and the conditions of its communication are still too little known to enable a final opinion to be given as to the measures necessary to its complete extermination. The experience of the last six months has proved, however, that very valuable results can be attained by sheer force of a thorough and persistent cleansing of accessible surfaces and localities, and this demonstration is worth a hundred times the cost of making it.” See Ludlow, William. (1899). “Annual report of the Department of Havana and Military Governorship of Havana, December 22, 1898 to June 30, 1899.” In

Annual Report of Major General John R. Brooke, U.S. Army, Commanding the Division of Cuba. Havana: United States Government.

p. 38.

[4] See Ludlow, William. (1899). “Annual report of the Department of Havana and Military Governorship of Havana, December 22, 1898 to June 30, 1899.” In

Annual Report of Major General John R. Brooke, U.S. Army, Commanding the Division of Cuba. Havana: United States Government.

pp. 43-46.

[5] U.S. officials in Cuba recognized the connection between

immigration and the outbreak of yellow fever epidemics in Cuba. In February 1901, the chief surgeon of the occupation government, Major Valery Havard, in a report on sanitation and yellow fever in Havana, wrote the following: “During the years 1899 and 1900, 40,384 immigrants arrived at Havana, namely 16,260 in 1899 and 24,124 in 1900, a great majority of them non-immunes and at least 50 percent remaining in the city of Havana. They still continue to come at about the same rate. With these figures of the largest immigration on record in the same space of time, what happened was to be expected and unavoidable, namely, an unusually large number of cases of yellow fever in the summer and fall of 1900 and corresponding high mortality, although the deaths (310) did not reach the annual average of the past decade.” See Havard, V. (1901). “Sanitation and yellow fever in Havana, report of Major V. Havard, Surgeon U.S.A.” In

Civil Report of Major General Wood, Military Governor of Cuba 1900, Vol. 4. Havana: United States Government. p. 12-13.

[6] Military orders regarding the appointment of a board to study infectious diseases in Cuba, May 24, 1900.

Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995, Box-folder 20:19. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.