Before the U.S. Army Commission published its findings in 1901, yellow fever was a serious threat in the United States. While other diseases in the country were more prevalent and more deadly, no other could generate as much terror. It spread unpredictably and could kill 20% of a city’s population over the course of two to three months. The virus also unraveled the social fabric of the communities it struck—creating refugee populations, undermining trusted institutions, and dissolving familial bonds.

“The Exodus from Newport News Caused by the Yellow Fever Outbreak,” Harper’s Weekly, August 12, 1899.

Yellow Fever in Coastal Cities: Boston, Philadelphia, New York, New Orleans

In 1693, the first irrefutable outbreak of yellow fever in North America likely occurred in Boston, although there has been some evidence of earlier outbreaks. [1] For the next 200 years, the disease regularly visited Boston and other coastal cities in North America. Outbreaks generally followed a common and frightening progression. During the summer, a ship from a region where the disease was endemic, most often the Caribbean, arrived with infected passengers. Soon after, isolated cases of yellow fever occurred in the city. A week or two later, the disease rapidly spread through the whole population. Finally, without explanation, the outbreak quickly subsided as winter approached and temperatures dropped.

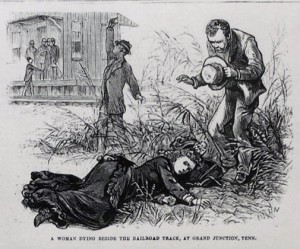

Excerpt “The Great Yellow Fever Scourge-Incidents of its Horrors in the Most Fatal Districts of the Southern States. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, September 28, 1878.

An especially deadly series of outbreaks in North American cities during the 1790s terrified the inhabitants of the newly-formed United States. During the U.S. War of Independence, disruption of commerce between the United States and the rest of the world discouraged the spread of yellow fever from endemic regions to the nation’s seaports. After the war, the formation of the federal government led to an expansion in international trade and encouraged the migration of large non-immune populations to the prospering coastal cities. These factors together facilitated the spread of yellow fever. Outbreaks occurred in nearly all the major coastal cities of the nation, with particularly deadly ones in Philadelphia and New York. In Philadelphia, the temporary capital of the nation, three outbreaks of yellow fever during this period shut down the new federal government, paralyzed commerce, and killed almost 10% of the city’s population. [2]

The outbreaks in Philadelphia and other northeastern ports during the 1790s spurred a modest public health movement in the northern United States. Although the cause of yellow fever and how it was transmitted was still a mystery, local and state governments implemented strict quarantine systems and sanitation ordinances hoping that they could prevent future outbreaks. [3] Researchers do not fully understand how effective these measures were in preventing the spread of yellow fever, but there is a strong correlation between public health reforms in the northern cities and the absence of major outbreaks in those communities after 1822.

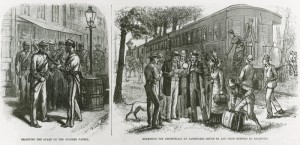

Scenes of Memphis, Tennessee under Quarantine for a Yellow Fever Outbreak. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, September 20, 1879.

Yellow fever continued to plague southern ports throughout the rest of the 19th century. The worst epidemic occurred in 1878, when an outbreak in New Orleans spread into the lower Mississippi Valley infecting at least 120,000 and killing between 13,000 and 20,000 Americans. [4] Similar to the outbreaks of the 1790s, the 1878 epidemic that started in Louisiana spurred a new public health campaign in the Southern United States and created a new urgency within the U.S. medical community to discover the cause of yellow fever. [5] ”Sources“