A Girl Suffering from Yellow Fever, watercolour by an unknown artist, 1800s. Wellcome Library, London. images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org

In 1900, when the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission completed its landmark work, the scientific community was just beginning to understand the yellow fever virus. Today we know a great deal more about this deadly disease.

Yellow fever belongs to a group of illnesses called viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs). VHFs, which also include dengue fever and ebola, are viruses that affect multiples organ systems in the human body and cause severe bleeding. According to the World Health Organization:

Once contracted, the [yellow fever] virus incubates in the body for 3 to 6 days, followed by infection that can occur in one or two phases. The first, “acute,” phase usually causes fever, muscle pain with prominent backache, headache, shivers, loss of appetite, and nausea or vomiting. Most patients improve and their symptoms disappear after three to four days. [1]

However, 15% of patients enter a second, more toxic phase within 24 hours of the initial remission. High fever returns and several body symptoms are affected. The patient rapidly develops jaundice and complains of abdominal pain with vomiting. Bleeding can occur from the mouth, nose, eyes or stomach. Once this happens, blood appears in the vomit and feces. Kidney function deteriorates. Half of the patients who enter the toxic phase die within 10 to 14 days, the rest recover without significant organ damage.” [2]

Mosquito Transmission of Yellow Fever

Yellow fever, as the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission verified, is primarily transmitted to humans by mosquitoes. A mosquito either inherits the virus from its mother or contracts it when it bites another animal infected with the disease. After an incubation period, the mosquito may then transfer the virus to healthy subjects it bites. Those who survive infection of yellow fever acquire a lifelong immunity to it.

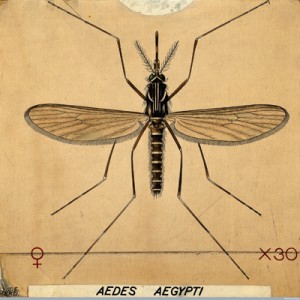

The Aedes Aegypti Mosquito, coloured drawing by Amedeo John Engel Terzi. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London, Wellcome Images: images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org/

Three epidemiological cycles, urban, intermediate, and sylvanic, characterize the spread of yellow fever. Major outbreaks of the disease are associated with urban cycles. In these kinds of outbreaks, female members of the mosquito species Aedes aegypti, which are well-adapted to built environments, spread the virus in dense populations. [3] Without human intervention, urban outbreaks end when cold weather kills the mosquitoes or when most of the host population acquires immunity to the virus.

The evolutionary origins of yellow fever are unknown, but the most popular theory is that the disease originated in West Africa and spread to the Americas and Europe in the 17th century. The proponents of this theory believe that ships participating in the trans-Atlantic slave trade carried infected mosquitoes and passengers from Africa to Europe and its colonies. [4] The disease soon became endemic in areas of the Western Hemisphere where there was a tropical climate and a steady flow of non-immune immigrants.

”Sources“