In May of 1900, George Miller Sternberg appointed four men to serve on the new U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission. The head of the Commission was Major Walter Reed, a career military officer who was widely recognized as one of the leading bacteriologists in the army. The other appointees were Dr. James Carroll, Reed’s research assistant in Washington, D.C.; Dr. Aristides Agramonte, a U.S. Army surgeon who had been researching yellow fever in Cuba for almost two years; and Dr. Jesse Lazear, a scientist from Johns Hopkins Hospital who had joined the army to study tropical diseases at their point of origin.

Experiments to Discover the Cause of Yellow Fever

Aristides Agramonte, Jesse Lazear, and James Carroll (l.-r.) in Cuba, August 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995, Box-folder 76:5. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

George Sternberg ordered the members of the Commission to report to the Columbia Barracks Hospital outside of Havana, Cuba, in June of 1900. Their first task was to determine if a species of bacteria called Bacillus icteroides was the cause of yellow fever, and in the event that it was not, then they were then to analyze blood and intestinal flora from yellow fever cases to determine other possible causes. [1] In 1897, Italian scientist Giuseppe Sanarelli argued that Bacillus icteroides was the cause of yellow fever, and soon after, researchers Eugene Wasdin and Henry D. Geddings claimed to have confirmed Sanarelli’s discovery in Cuba. Sternberg and Reed, who had both studied the relationship of the bacteria to yellow fever, disagreed with these claims and wanted to gather conclusive evidence to refute Sanarelli, Wasdin, and Geddings. [2]

Bacillus icteroides and other bacteriological sampling dominated the work of the Commission for the first months. “Reed and Carroll have been at that for a long time,” Lazear wrote with some impatience to his wife on August 23, “. . . I would rather try to find the germ without bothering about Sanarelli.” [3] Again and again, tests for the bacteria proved negative, and at the same time, perplexing cases of yellow fever were developing in the region. Agramonte and Reed investigated an epidemic at Pinar del Rio, 110 miles southwest of Havana; Lazear followed later to collect more specimens, and he also assessed the situation at Guanjay thirty miles southwest. To “my very great surprise,” Reed admitted, the specific circumstances of the appearance and development of these cases gave strong evidence against the widely-accepted notion that the excreta of patients spread the disease. The theory of fomites — infection from contaminated clothing and bedding — and indeed even infection from airborne particles seemed altogether untrue. “At this stage of our investigation,” Reed concluded, “. . . the time had arrived when the plan of our work should be radically changed.” [4] The fundamental question underwent a subtle but critical transformation: from what causes yellow fever to what transmits it. A clear and accurate understanding of how the disease was spread would open a new avenue to its specific cause.

A recent discovery made by Henry Rose Carter, of the U.S. Marine Hospital Service, provided the Commission with a critical lead in their new investigation. In 1898, Carter, while stationed in Mississippi, observed that it took approximately 10 to 17 days for yellow fever to spread from one person to another. This suggested to Carter that an intermediate host was the vector for yellow fever. [5] Shortly after he made this observation, Carter was reassigned to Cuba, where he came into contact with Jesse Lazear. Carter shared his unpublished observations with Jesse Lazear, and he argued that his findings suggested that Carlos Finlay’s theory could be correct and Finlay’s experiments may have been inconclusive because he did not take into account the possibility of an incubation period. [6]

Review of Troops at Camp Columbia, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995. Box-folder 90:6. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

Evidence gathering around them pointed strongly to an intermediate host, and the Commission resolved to test Carlos Finlay’s mosquito theory — then not generally accepted — on human volunteers. Nine times from August 11 to August 25, 1900, mosquitoes landed on the arms of volunteers and proceeded to feed. Nine times the results were negative. On August 27, Lazear placed a mosquito on the doubting Dr. Carroll, and four days later on William J. Dean, a soldier designated XY in the “Preliminary Note.” [7] Both promptly developed yellow fever. Significantly, their mosquitoes had fed on cases within the initial three days of an attack and had been allowed to ripen for at least twelve days before the inoculations. Carroll undermined the results of his experimental sickness by traveling away from the semi-secluded army post to Havana. Critics of the mosquito theory could argue that Carroll had been infected in the city, where the disease was endemic, by other means. Even so, Reed, ecstatic, wrote from Washington in a confidential letter: “Did the Mosquito do it?” [8] Dean’s case seemed to prove it, since he claimed not to have left the garrison before becoming ill. Lazear also developed a case of yellow fever, almost certainly experimental in origin, though he never revealed the actual circumstances of his inoculation. His severe bout of fever took a fatal turn on September 25, 1900.

Jesse W. Lazear, circa 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995. Box-folder 94:15. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

These results could not have been more dramatic or convincing for the Commission. Reed quickly assembled a “Preliminary Note,” which he presented to the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association in Indianapolis, Indiana on October 23, 1900. [9] After initial consultations in Cuba with General Leonard Wood, military governor of the island, and with Surgeon General Sternberg in Washington, Reed returned to Cuba with authorization and funding to design and carry forward a fully defensible series of experiments. His aim was confirmation of the mosquito theory and invalidation of the long-held belief in fomites. [10]

Mosquitoes and Blood Transmit Yellow Fever

On open terrain beyond the precincts of Columbia Barracks — the American military base just west of Havana near the adjacent suburban towns of Quemados and Marianao (also called Quemados de Marianao) — Reed established a quarantined experimental station. Camp Lazear, as the Commission dedicated it, took form in the rolling fields of the Finca San Jose, on the farm of Dr. Ignacio Rojas, who leased the land to the Americans. [11] Here the Army built two small wood-frame buildings for the experimental work, and nearby a group of tents was raised for the accommodation and support of the volunteers.

Camp Lazear went into quarantine the day of its completion, November 20, 1900, with a command of four immune and nine non-immune individuals, all save one, U.S. Army personnel. Soon a group of recent Spanish immigrants to Cuba augmented the non-immune numbers, bringing the resident total to about twenty. [12] Reed strictly controlled access to the camp and ordered regular temperature recording for each volunteer to eliminate any unanticipated source of infection and to identify the onset of any case of yellow fever as early as possible. As a result, non-immunes were barred from returning should they leave the precinct, and two of the Spaniards who developed intermittent fevers shortly after arrival were immediately transferred with their baggage to Columbia Barracks Hospital. [13] The immune members of the detachment oversaw medical treatments and drove the teams of mules that pulled supply wagons and the ambulance. Experimentation did not begin until each volunteer had passed the incubation period for yellow fever in perfect health. [14]

Composite Sketch of Camp Lazear, undated. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995. Box-folder 90:24. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

The Commission’s mosquito experiments proceeded in several series. First, Reed sought to demonstrate that mosquitoes of the variety Culex fasciata (later called Stegomyia fasciata, and later still Aedes aegypti) could in fact transmit yellow fever, as Carlos J. Finlay had argued and the initial experiments at Camp Columbia strongly suggested. Here the Commission members simply applied infected mosquitoes contained in test tubes or jars to the skin of several volunteers. The first inoculations of four volunteers over a period of two weeks proved disconcertingly negative each time. Then, on December 5, 1900, private John R. Kissinger presented his arm to the mosquitoes, and late in the evening on December 8, suffered the first chills of “a well-marked attack of yellow fever.” Three more men in rapid succession fell victim to the insects — Spanish volunteers Antonio Benigno, Nicanor Fernandez, and Vicente Presedo. [15]

“It can readily be imagined,” Reed empathetically and wryly described in his first presentation of the experiments, “that the concurrence of 4 cases of yellow fever in our small command of 12 nonimmunes within the space of 1 week, while giving rise to feelings of exultation in the hearts of the experimenters, in view of the vast importance attaching to these results, might inspire quite other sentiments in the bosoms of those who had previously consented to submit themselves to the mosquito’s bite. In fact, several of our good-natured Spanish friends who had jokingly compared our mosquitoes to ‘the little flies that buzzed harmlessly about their tables,’ suddenly appeared to lose all interest in the progress of science, and, forgetting for the moment even their own personal aggrandizement, incontinently severed their connection with Camp Lazear. Personally, while lamenting to some extent their departure, I could not but feel that in placing themselves beyond our control they were exercising the soundest judgment.” [16]

After establishing that yellow fever can be transmitted by a mosquito, the Yellow Fever Commission conducted another experiment to determine if the disease could be conveyed by blood injection and to conclusively show that Bacillus icteroides was not the cause of yellow fever. Four non-immune volunteers were given subcutaneous injections of blood taken from a patient suffering from yellow fever and then tested for Bacillus icteroides. Three of the volunteers caught yellow fever, suggesting to the Commission that yellow fever could be conveyed by either injection or mosquito. All of the volunteers tested negative for Bacillus icteroides, which conclusively invalidated Sanarelli’s claim about the bacteria. [17]

Yellow Fever Not Transmitted by Fomites

Building No. 1 (Fomites Building, at Camp Lazear, February 1901. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995. Box-folder 90:12. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

Next the Yellow Fever Commission wanted to conduct an experiment to determine if yellow fever could be transmitted by fomites. For this experiment, Walter Reed designed two wood frame buildings, each 14 by 20 feet in size. The buildings faced each other across a small swale, about 80 yards apart, and stood 75 yards from the tent encampment. Building Number One, called the Infected Clothing Building, was a single room tightly constructed to contain as much foul air as possible. A small stove kept the temperature and humidity at tropical levels, and carefully attached screening secured the pair of doorways in a vestibule against intrusion by mosquitoes. Wooden blinds on two small sealed windows shielded the room from direct sun. Building Number Two, the Infected Mosquito Building, contained a principal room, divided into two sections by a floor-to-ceiling wire mesh screen. A door direct to the exterior led into one section, while a vestibule with a solid exterior door and pair of successive screened doors opened to the other, so configured to keep infected mosquitoes inside that section alone. The spare furnishings in both sections — cots with bedding — were steam sterilized. Windows exposed the entire room to the clean, steady ocean breezes and to sunlight. Like the doorways, they were carefully screened. A secondary room attached to the building but not communicating with the experimental spaces sheltered the small, heated laboratory where the Commission members raised and stored the mosquitoes to be used. [18]

These two experimental buildings presented alternate environments — one conspicuously clean and well ventilated, the other filthy and fetid. Contemporary theories of disease held that yellow fever developed in unclean conditions, and consequently much time and money had been devoted to sanitation projects. Workers steamed clothing, burned sulphur in ships’ holds, and thoroughly scrubbed surfaces with disinfectant. In cases of severe epidemic, entire buildings presumed to be infected were set afire along with their contents. Thus the extraordinary — and intentional — paradox of the Commission’s experimental regime: Reed expected yellow fever to develop not in the unsanitary environment, but in the one thought to be most healthful.

Reed took as much care with the design of the experimental protocol as he had with the configuration of the buildings. Each evening, the occupants of the Infected Clothing Building unpacked trunks and boxes of bed linens and blankets, nightshirts and other clothing recently worn and soiled by cases from the wards of Columbia Barracks Hospital and Las Animas Hospital in Havana. These they shook out and spread around the room to permeate the atmosphere. [19] The stench was overpowering. Yellow fever causes severe internal hemorrhaging, and its unfortunate victims often suffer from black vomit and other bloody discharges. One routine delivery proved so putrid the volunteers “retreated from the house,” Reed stated. “They pluckily returned, however, within a short time, and spent the night as usual.” [20] In two succeeding trials the protocol became progressively more daring, as the volunteers then wore the clothing and slept on the mattresses used by yellow fever patients, and finally put towels on their bedding smeared with blood drawn from cases in the early stages of an attack. Each morning, the volunteers carefully repacked the rank, encrusted materials into boxes and emerged to an adjacent tent where they spent the day quarantined from the rest of the company. [21] Three trials of twenty days each involved seven men altogether, led by Robert P. Cooke, a physician in the Army Medical Corps. [22] None developed yellow fever.

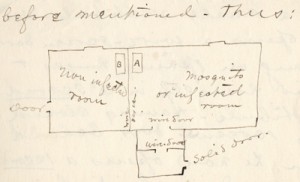

Walter Reed’s sketch of Building Number 2 at Camp Lazear (Mosquito Building), circa December 25, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995. Box-folder 22:57. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

The Infected Mosquito Building, Building Number Two, required two groups of volunteers, one to be inoculated and another to serve as controls. “Loaded” mosquitoes, as the men called them, were released into the screened section of Building Two — on the side with the protected vestibule entry. One or more non-immune men then entered the opposite section of the room through the direct exterior door, and lay down on bunks adjacent to the wire mesh screen in the center of the room. Then the young man to be inoculated walked through the vestibule into the mosquito side of the room and proceeded to lie on a bunk adjacent to the wire screen separating him from the controls. The inoculation volunteer remained in the building for about twenty minutes — enough time to suffer several mosquito bites — he then exited to a quarantine tent outside. The controls spent the remainder of the evening and night in the uninfected side of the room, and indeed returned to sleep in the room for as many as eighteen more nights. [23] As Reed stated, the continued absence of yellow fever in the controls showed “that the essential factor in the infection of a building with yellow fever is the presence therein of [infected] mosquitoes,” and nothing more. [24] The degree of sanitation, so long considered critical, was utterly irrelevant.

Mosquitoes Need Incubation Period to Infect Humans

The final experiment at Camp Lazear confirmed what Henry Rose Carter called the “period of extrinsic incubation,” [25] the length of time required for secondary cases of yellow fever to develop after an initial intrusion of the disease into a locality. In this series of experiments, a single volunteer underwent three successive inoculations by the same mosquitoes, each group of inoculations interrupted by a period of time equal in length to the typical incubation period of the disease in humans, about five days. [26] In this manner, the volunteer’s illness could be specifically attributed to a single inoculation group. The use of the same mosquitoes and the same volunteer concurrently demonstrated that no peculiar personal immunity was at play, since logic dictates that a person susceptible to yellow fever on day 17 of a mosquito’s contamination — as happened in the experiment — could not have been immune to yellow fever on day 11 or day 4. It was thus only the mosquito’s capacity to infect which changed, and that occurred no less than 11 days after contamination. [27]

The duration of time over which these “fully ripened” mosquitoes remained infective comprised the fourth series of experiments. For this series, the Commission kept alive a group of infected mosquitoes for as long as possible, and proceeded to inoculate three volunteers — on the 39th, 51st, and 57th day after contamination. Each developed yellow fever. A fourth volunteer declined to be bitten on day 65, and the last two mosquitoes of the group, “deprived of further opportunity to feed on human blood,” expired on day 69 and day 71, clear evidence that even a sparsely populated region may retain the potential for new infections more than two months after the first appearance of the disease. [28]

Altogether, the mosquito inoculations and the blood injections produced fourteen cases of yellow fever. All made a full recovery. [29]

Walter Reed and Informed Consent

Personnel of the Camp Columbia Hospital, September 1900. Much of the personnel shown here assisted in the Yellow Fever Commission experiments. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995. Historical Collections. Box-folder 76:93. Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

The question of human experimentation was indeed a serious one — unavoidable, in actuality, as Reed had stated the previous summer to Surgeon General Sternberg. [30] When the Commission first considered a trial of Finlay’s mosquito theory, Reed, Carroll, and Lazear agreed to experiment on themselves. Agramonte, a native Cuban, had acquired immunity as a child. Doubtless Finlay’s experience of many unsuccessful inoculations communicated that positive results would not be forthcoming rapidly, so before the first series of inoculations began under Lazear’s direction at Columbia Barracks, Reed returned to Washington to spend time on other work. [31] Carroll and Lazear both sickened while Reed was in Washington, and Lazear, young and strong, had no reason to anticipate that his case would be fatal. Reed was shocked at Lazear’s death, and because of his own age — 49, a decade and a half older than Lazear and a dozen years older than Carroll — he resolved not to inoculate himself when he returned to Cuba on October 4, 1900. [32]

That initial series of mosquito inoculations was probably accomplished without formal documentation of informed consent. Indeed, the experiments may also have been carried forward without the full knowledge of the commanding officer of Camp Columbia, and Reed consequently shielded the identity of Private William J. Dean, the second positive experimental case, behind the pseudonym “XY” in the “Preliminary Note.” [33] For the experiments at Camp Lazear, Reed tried to address concerns in the Cuban press about U.S. experimentation on their citizens and recent immigrants from Spain by obtaining prior support from appropriate authorities in the military and the administration.[34] With the advice of the Commission and others, he also drafted what is now one of the oldest series of extant informed consent documents. The surviving examples are in Spanish with English translations, and were signed by volunteers Antonio Benigno and Vicente Presedo, and a third with the mark of Nicanor Fernandez, who was illiterate. [35]

The documents take the form of a contract between individual volunteers and the Commission, represented by Reed. At least 25 years old, each volunteer explicitly consented to participate, and balanced the certainty of contracting yellow fever in the general population against the risks of developing an experimental case, followed by expert and timely medical care. The volunteers agreed to remain at Camp Lazear for the duration of the experiments, and as a reward for participation would receive $100 “in American gold,” with an additional hundred-dollar supplement for contracting yellow fever. These payments could be assigned to a survivor, in the case of the participant’s death, and the volunteers agreed to forfeit any remuneration in cases of desertion. [36]

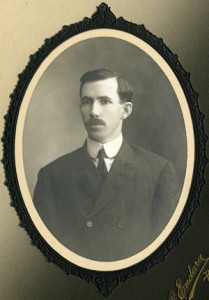

John J. Moran, circa 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995. Box-folder 80:38. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

For the American participants no consent documents appear to survive, though in contemporary letters Reed assured his correspondents that the Commission obtained written consent from all the volunteers. [37] The record of expenses for Camp Lazear — maintained by Reed’s friend and colleague in the Medical Corps, Jefferson Randolph Kean — indicates that the same schedule of payments for participation and sickness applied to the Americans as well. Volunteers who participated in the fomites tests, the later series of blood injections, and the single trial of an alternative species of mosquito also earned $100 each plus the $100 supplement if yellow fever developed. [38] Two Americans declined compensation, Dr. Robert P. Cooke, of the fomites tests, and John J. Moran, who had recently received an honorable discharge from the service, and was the only American civilian to participate. [39] His was the fourth case of yellow fever to develop from mosquito inoculation. Moran eventually settled in Cuba, where he managed the Havana offices of the Sun Oil Company, and late in life became a close friend of Philip S. Hench. Together the two men rediscovered the site of Camp Lazear in 1940 — Building Number One still intact — and successfully lobbied the Cuban government to memorialize there the work of Finlay and the American Commission in the conquest of yellow fever. [40]

The Yellow Fever Commission Disbands

Reed informally commemorated his own experiences at Camp Lazear by commissioning a group photograph, evidently taken there shortly before he left Cuba in February 1901. A more important event occurred on the sixth of that month when Reed presented the results of the Camp Lazear yellow fever experiments to a great ovation at the Pan-American Medical Congress in Havana. Three days later he set sail for the United States, and, once landed, drafted the Congress paper as “The Etiology of Yellow Fever — An Additional Note,” published immediately in the Journal of the American Medical Association. [41]

Though his correspondence intimates a great appreciation for Cuba, Reed never returned to the warm, sunny shores of the island freed of a dreadful plague. Carroll stayed behind at Camp Lazear through February to complete the last experimental series officially bearing the imprimatur of the Yellow Fever Commission, and returned to Washington soon after March first. [42] The Medical Corps retained the lease on Camp Lazear against the possibility of continuing experiments another season, and Carroll, in fact, returned to Havana in August 1901 for a final experimental series, though he did not make use of Camp Lazear. [43] This work involved at least three volunteers at Las Animas Hospital, Havana, who submitted to blood injections. Carroll’s assignment aimed at a greater understanding of the yellow fever agent, and he proved that blood drawn from active cases of yellow fever remained virulent even after passing through fine bacteria filters. In addition, by heating contaminated blood which had previously caused cases of yellow fever, Carroll rendered it non-infective — thereby establishing that this non-filterable entity, though sub-microscopic, was demonstrably present in the bloodstream. Carroll wrapped up the series in October and returned home. [44] In Cuba, J. Randolph Kean made the last rental payments to Signore Rojas on October 9, 1901, and Camp Lazear, for more than a generation, slipped out of the realm of memory. [45]

”Sources“