Yellow Fever Research & Mosquito Control

Mosquito Control by Pesticides, Reduction of Breeding Areas, and Larva-eating Fish

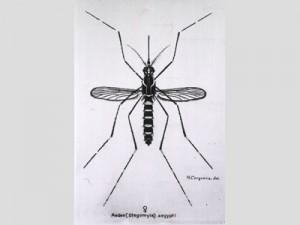

“Aedes (Stegonyia) aegypti” mosquito. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.[1] (Translation: aëdes (place of refuge or rest / house) aegypti (of Egypt / Aegyptus, the mythical king of Egypt whose fifty sons married the fifty daughters of his twin brother Danaus.)[2]

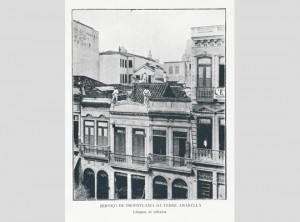

“1918: Anti-Mosquito Methods Control Yellow Fever in Ecuador.” Courtesy of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.[3] |

Pesticides: Mosquito squads were employed to spray chemicals on rooftops and other surfaces as shown in this picture taken in Guayaquil, Ecuador which features one of 25 mosquito squads assigned to the work. |

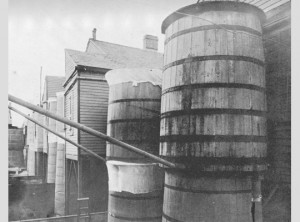

Cheesecloth over water cisterns in New Orleans, 1905 from Yellow Fever Prophylaxis in New Orleans 1905 by Robert Boyce, published in 1906.”[4] |

Eliminate mosquito breeding: Community water tanks, household water containers, and any other object that would potentially hold standing water (a prime environment for the mosquito to lay eggs) were sealed. Various materials were utilized, such as the cheesecloth over the cisterns in this image taken during the 1905 New Orleans outbreak. |

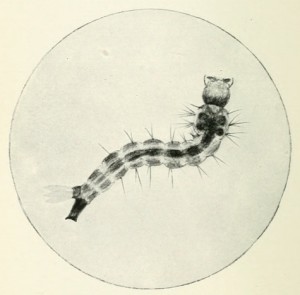

Larva as depicted in the West African Pocket Book, 1920.[5] |

Weekly house inspections: As a field inspector in West Africa, Dr. Hanson used this method to detect and destroy mosquito larvae. Hanson made frequent references to the “household index,” which is the percentage of houses that were found to have Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. The goal was to achieve a percentage under two percent.[6] |

One of the fish species used in Colombia’s fight against yellow fever, 1924.[7] |

Larva-eating fish: Dr. Hanson implemented this method in large water containers with significant success in Peru. Over “three hundred thousand fish” were distributed as larvae consumers in the campaign.[8] Hanson documented his results in the report, A Study of Sanitary Conditions in Peru with Special Reference to the Incidence of Malaria, published in 1921 by Panama Canal Press.[9] |

It’s Up to You: Dengue-Yellow Fever Control.[10] |

Public health campaigns continued to employ the same methods of mosquito control for many decades after the campaigns in South America and West Africa, as demonstrated in this 1945 U.S. Public Health Service film, It’s Up to You: Dengue-Yellow Fever Control. |

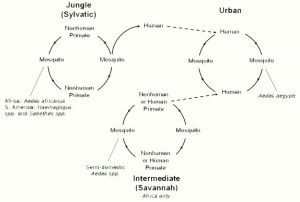

Transmission of the Yellow Fever Virus.[13]

Additional studies showed that mosquitoes other than Aedes aegypti contained the yellow fever virus: Haemagogus, Sabethine, and Aedes lencocelaenus in South America and Aedes africanus and Aedes simpsoni in Africa.[11]

Today researchers describe three transmission cycles for the yellow fever virus: jungle (sylvatic), intermediate (savannah), and urban as depicted in the graph created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The disease is transmitted in the jungle by mosquitoes between nonhuman primates; humans can get the virus when they visit the jungle. The infected person can then take the disease back to an urban area where the virus is generally transmitted from human to human by means of the Aedes aegypti. In Africa, the intermediate cycle involves yellow fever transmission from mosquitoes to humans who live or work in areas near the jungle border. The mosquitoes can be the disease vector from monkeys to humans or from humans to humans.[12]

Although, these discoveries led to the realization that total elimination of yellow fever vectors was not possible, fever fighters today still focus on the control of mosquito populations, as in the Florida Keys where the three basic methods are source reduction or reducing the number of habitat areas for larvae, larval control which targets the immature mosquitoes before they mature into biting adults, and the adult surveillance program which aims to count, collect, and control the adult mosquitoes. The technique of larvae-eating fish espoused by Dr. Hanson is still used.[14]

![]() Previous: Work in North America / Next: An Offer

Previous: Work in North America / Next: An Offer ![]()

- [1] “Aedes (Stegonyia [Stegomyia]) aegypti,” National Library of Medicine: Images from the History of Medicine, http://tinyurl.com/cqfn489 (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [2] The New College Latin and English Dictionary.

- [3] The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, “1918: Anti-Mosquito Methods Control Yellow Fever in Ecuador,” The History of Vaccines, Timelines, 2012, http://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/timelines/all (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [4] Wikimedia Commons, “File: Cisterns with cheesecloth New Orleans 1905,” http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cisterns_with_cheesecloth_New_Orleans_1905.jpg (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [5] The West African Pocket Book: A Guide for Newly Appointed Government Officers, Comp. by direction of the Secretary of State for the Colonies ([London]: Crown Agents for the Colonies, 1920), following 16, http://openlibrary.org/books/OL22896591M/The_West_African_pocket_book (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [6] Ilana Löwy, “Epidemiology, Immunology, and Yellow Fever: The Rockefeller Foundation in Brazil, 1923-1939,” Journal of the History of Biology 30, no. 3 (September 1997): 399, http://www.springerlink.com/content/n3ph82464j627338/ (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [7] C.H. Eigenmann,“Yellow Fever and Fishes in Colombia,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 63, no. 3 (1924): following 238.

- [8] Letter from Henry Hanson to the Director of Health, September 9, 1921, Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections, CMHSL, University of Virginia, http://search.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/uva-lib:2222891 (accessed May 23, 2017).

- [9] Marcos Cueto, “Sanitation from Above: Yellow Fever and Foreign Intervention in Peru, 1919-1922,” The Hispanic American Historical Review 72, no. 1 (February 1992): 7, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2515945 (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [10] U.S. Office of Malaria Control in War Areas, “It’s Up To You: Dengue-Yellow Fever Control (1945),” Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/ItsUpToYouDengue-yellowFeverControl1945 (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [11] Raymond B. Fosdick, The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1952), 65.

- [12] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Yellow Fever, Transmission of the Yellow Fever Virus,” December 13, 2011, http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/transmission/index.html (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [13] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Yellow Fever, Transmission of the Yellow Fever Virus,” December 13, 2011, http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/transmission/index.html (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [14] Edsel M. Fussell, “Mosquito Control in the Florida Keys,” Florida Keys Mosquito Control District, http://keysmosquito.org/about-us-2/about-the-keys-mosquito-control/ (accessed July 25, 2012).