A Brief History of the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Commission

From Hookworm to Yellow Fever

The original Rockefeller logo.[1]

In 1913, John D. Rockefeller, a man indoctrinated from his youth “to work, to save, and to give,”[2] established the Rockefeller Foundation, which ultimately became one of the most famous philanthropic institutions in the world. The Rockefeller Foundation and its International Health Commission (later Board in 1916 and then Division in 1927) ambitiously set out “to promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world.”[3] Under the leadership of Wickliffe Rose, the Foundation quickly achieved success in the United States with the hookworm campaign of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission. Rose was soon looking for a new disease to “attack,” one which met the criteria of being “of global importance, little was being done about it and it could be prevented at a reasonable cost.”[4]

Rose’s 1914 report to the Foundation, “Yellow Fever: Feasibility of its Eradication,”[5] marked the beginning of the Yellow Fever program which lasted until 1951 when Dr. Max Theiler won the Nobel Prize for his yellow fever vaccine, and the Foundation’s annual report stated, “in all likelihood yellow fever will cease to be a public health menace.”[6] Rose worked on his feasibility report in collaboration with three medical doctors: William Crawford Gorgas, Henry Rose Carter, and Joseph Hill White.

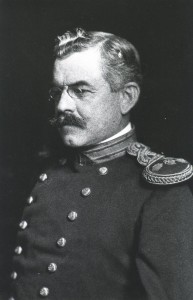

“William Crawford Gorgas, Surgeon General US Army Washington, D.C., July 22, 1917,” Hench-Reed Collection.[7] |

William Crawford Gorgas, M.D.,(1854-1920) attended college at the University of the South in Tennessee and medical school at Bellevue Medical College in New York City. He joined the Army Medical Corps in 1880, survived yellow fever at one of his Texas assignments, and was made a Surgeon General in 1914. He was credited with successfully eradicating yellow fever and controlling malaria in Panama as the chief sanitation officer during the construction of the Panama Canal which opened in 1914. In an early meeting with Rose, Gorgas commented that the eradication of yellow fever, “would command the attention and the gratitude of the world. And the thing can be done.”[8][9] |

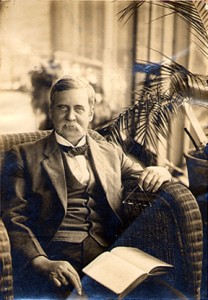

Henry R. Carter, Hench-Reed Collection.[10] |

Henry Rose Carter, M.D.,(1852-1925) was an 1873 graduate in civil engineering from the University of Virginia. He did post-graduate work in math and applied chemistry before he decided to study medicine. He obtained his medical degree from the University of Maryland in 1879 and joined the Marine Hospital Service which became the United States Public Health Service. He rose through the ranks to become Assistant Surgeon General in 1915. He was a prominent epidemiologist and leading yellow fever expert who studied the disease for years. His discovery of the “extrinsic incubation period” of the transmission was crucial to the Reed Commission’s ability to prove that the vector of the yellow fever virus was the Aedes aegypti mosquito.[11] |

“Joseph H. White, [192?].” Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.[12] |

Joseph Hill White, M.D.,(1859-1953) was born in Georgia and earned his medical degree from the Baltimore College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1883. He was an Assistant Surgeon General in the United States Public Health Service, called the Marine Hospital Service when he entered in 1884.[13] He used measures to eradicate mosquitoes to counter a yellow fever outbreak in Virginia in 1899 before the link between the two had been proven. His skillful handling of the 1905 yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans would prove valuable to the Rockefeller Foundation when he was loaned to them in 1914.[14] |

In Wickliffe Rose’s report on the feasibility of eradicating yellow fever, six locations were given as “Known Foci of Yellow Fever” with the first five locations in South America and the final location being “an African focus or group of foci on the West Coast from Sierra Leone south to the Gulf of Guinea.” Costs and length of time for eradicating the disease were also estimated in the report. With a “maximum cost at about $2.00 per capita for one year,” but only $1.50 a year when patient cases were excluded, the city of Guayaquil with a population of 80,000, was predicted to have an annual budget of $120,000. Varying time estimates were mentioned to do the work, but it was concluded that “taking all contingencies into consideration two years would seem to be a safer estimate of the time limit.”[15] Carter was so confident that yellow fever could be wiped out that he wrote to Rose, “I think you have rather exaggerated the difficulty of getting rid of yellow fever when you put two years as the time required. We know just what to do. There is no uncertainty in it.”[16]

![]() Previous: “Much Dreaded Disease” / Next: Yellow Fever in South America

Previous: “Much Dreaded Disease” / Next: Yellow Fever in South America ![]()

- [1] Wikipedia, “Rockefeller Foundation.”

- [2] Raymond B. Fosdick, The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1952), 4.

- [3] John R. Pierce and Jim Writer, Yellow Jack: How Yellow Fever Ravaged America and Walter Reed Discovered Its Deadly Secrets (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), 224.

- [4] L.W. Hackett, “Once Upon a Time: Presidential Address,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 9, no. 2 (March 1960): 109, http://www.ajtmh.org/content/9/2/105.full.pdf+html (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [5] Wickliffe Rose, “Yellow Fever: Feasibility of its Eradication,” October 27, 1914, Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections, CMHSL, University of Virginia, http://search.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/uva-lib:2222501 (accessed May 17, 2017).

- [6] The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1951 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, [1952]), 126, https://assets.rockefellerfoundation.org/app/uploads/20150530122203/Annual-Report-1951.pdf (accessed May 23, 2017).

- [7] “William Crawford Gorgas,” Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections, CMHSL, University of Virginia, http://search.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/uva-lib:2230758 (accessed May 17, 2017).

- [8] Harvard University Library, “William Gorgas, 1854-1920,” Contagion: Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics, http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/contagion/gorgas.html (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [9] Memorandum of interview with William Crawford Gorgas, July 14, 1914, Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections, CMHSL, University of Virginia, http://search.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/uva-lib:2225383 (accessed May 17, 2017).

- [10] Henry Rose Carter, Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections, CMHSL, University of Virginia, http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/yellowfever/henry-rose-carter-1852-1925-2/ (accessed May 17, 2017).

- [11] Henry Rose Carter, Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections, CMHSL, University of Virginia, http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/yellowfever/henry-rose-carter-1852-1925-2/ (accessed May 17, 2017).

- [12] “Joseph H. White,” National Library of Medicine: Images from the History of Medicine, https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101431986-img (accessed May 17, 2017).

- [13] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “U.S. Public Health Service History Commissioned Corps,” November 22, 2011, http://www.usphs.gov/aboutus/history.aspx (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [14] E. Lorene Flanders, “Joseph Hill White (1859-1953),” The New Georgia Encyclopedia, Science & Medicine, December 9, 2003, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-1099 (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [15] Wickliffe Rose, “Yellow Fever: Feasibility of its Eradication,” October 27, 1914, Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections, CMHSL, University of Virginia, 1, 11-12, http://search.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/uva-lib:2222501 (accessed May 17, 2017).

- [16] L.W. Hackett, “Once Upon a Time: Presidential Address,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 9, no. 2 (March 1960): 114, http://www.ajtmh.org/content/9/2/105.full.pdf+html (accessed July 25, 2012).