The West Africa Yellow Fever Commission, 1925-1934

Yellow Fever Research Progresses, but at the Cost of Commission Members Lives

The majority of the Commission members arrived in West Africa in July 1925 with four goals: “to learn the characteristics and epidemiology of yellow fever in West Africa and its relationship to the fever in the Western Hemisphere; to attempt the isolation of the organism that causes the disease; to discover the method of transmission; and to identify those areas in which the disease is continually present.”[1]

Dr. Henry Beeuwkes, a U.S. Army colonel who had achieved fame with his work battling typhoid and cholera outbreaks in Russia, was in charge of the West Africa Yellow Fever Commission.[2] Headquarters and a laboratory in Yaba, near the capital city of Lagos, were immediately established, and other locations were soon set up as well.[3]

“Animal Houses of the Yellow Fever Laboratory, Lagos, Nigeria,” January 20, 1933. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.[6]

A Rockefeller report described the Commission’s “outpost” in West Africa: “Five miles north of Lagos, in Nigeria, on the road to inland towns and cities, is a small settlement. On seven and a half acres are six main buildings – an office, a laboratory, an animal house, two dormitories, and a staff house. They are of the portable, sectional type, brought from America and set high on pillars of concrete. They are well equipped for scientific work and for living purposes. There is running water and electric light. A tennis court has been laid out. Modest landscape-gardening has been begun. Additional structures for kitchens, servants’ quarters, and storage have been built locally. Here live and work expert field directors, clinicians, laboratory men, assistants, and servants.”[4] The headquarters provided a central spot for what would become essentially a “field program with a rotating staff” among the Nigerian population of “approximately 99,000 Africans and 1,000 British.”[5]

“Laboratory building of the Yellow Fever Laboratory, Lagos, Nigeria,” January 20, 1933. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.[7]

The Commission’s goals would not be met until the late 1920s when a series of discoveries occurred in quick succession. In the summer of 1927, Dr. Alexander F. Mahaffy drew blood from a yellow fever victim, a 28 year old man named Asibi, from the Gold Coast, now Ghana. (This marked an historic moment in the fight against yellow fever as Asibi’s blood was eventually used to develop the first successful vaccine, 17D. Asibi survived and was given a pension in 1945.[8])

Dr. Mahaffy then returned to the lab in Accra where he injected Asibi’s blood into two different species of monkeys and two guinea pigs. The Macaus rhesus monkey became ill, and thus began the first successful transmission of yellow fever to animals. Then, the Commission showed that the “agent of yellow fever passed through a Berkefeld filter,” confirming the experiments of James Carroll from 1901. And finally, they produced a “convalescent serum from the severe cases of yellow fever” which “protected susceptible monkeys from the virus.”[9]

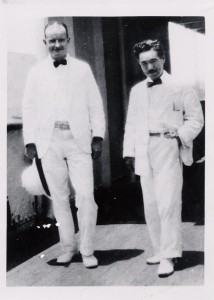

Hideyo Noguchi with C.B. Philip. Hench-Reed Collection.[11]

These advances were not without cost as the Commission experienced its first tragedy in the death of Adrian Stokes, who contracted yellow fever and died on September 19, 1927. Publishing their findings, in the 1928 article, “Experimental Transmission of Yellow Fever Virus to Laboratory Animals,” the authors note, “no spirochetes, leptospira, or other forms of microorganism were found in tissues of infected animals stained by Giemsa and Levaditi methods.”[10]

In 1927, as Hanson was departing West Africa, Hideyo Noguchi arrived to investigate the claim that his discovery of the Leptospira as the causative agent of yellow fever was incorrect. The photo to the left was taken on May 11, 1928, on board a steamship in Lagos Harbor, Nigeria. This is the last photo of Noguchi who had a headache at this time and was taken the next day to a hospital. Tragically, Noguchi had contracted yellow fever which led to his death in Accra on May 21, 1928. Several days later his assistant, William A. Young, who performed Noguchi’s autopsy, also succumbed to the disease.

![]() Previous: Why West Africa? / Next: Fever Fighters

Previous: Why West Africa? / Next: Fever Fighters ![]()

- [1] The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1926 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, [1927]), 224, https://assets.rockefellerfoundation.org/app/uploads/20150530122104/Annual-Report-1926.pdf (accessed May 23, 2017).

- [2] “Relief Checking Disease in Russia” New York Times, April 25, 1922.

- [3] John R. Pierce and Jim Writer, Yellow Jack: How Yellow Fever Ravaged America and Walter Reed Discovered Its Deadly Secrets (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), 227-228.

- [4] The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1926 (New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, [1927]), 40-41, https://assets.rockefellerfoundation.org/app/uploads/20150530122104/Annual-Report-1926.pdf (accessed May 23, 2017).

- [5] Greer Williams, The Plague Killers (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969), 226.

- [6] “Animal houses of the Yellow Fever Laboratory, Lagos, Nigeria,” National Library of Medicine, Profiles in Science: The Wilbur A. Sawyer Papers, http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/retrieve/ResourceMetadata/LWBBGF (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [7] “Laboratory building of the Yellow Fever Laboratory, Lagos, Nigeria,” National Library of Medicine, Profiles in Science: The Wilbur A. Sawyer Papers, http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/retrieve/ResourceMetadata/LWBBGH (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [8] “First Human Yellow Fever ‘Guinea Pig’ Gets Pension,” New York Times, December 22, 1945.

- [9] John R. Pierce and Jim Writer, Yellow Jack: How Yellow Fever Ravaged America and Walter Reed Discovered Its Deadly Secrets (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), 228.

- [10] Adrian Stokes, Johannes H. Bauer, and N. Paul Hudson, “Experimental Transmission of Yellow Fever Virus to Laboratory Animals,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine 8, no. 2 (March, 1928): 163, http://www.ajtmh.org/content/s1-8/2/103.full.pdf+html (accessed July 25, 2012).

- [11] Photograph of B. Philip and Hideyo Noguchi, May 11, 1928, Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections, CMHSL, University of Virginia, http://search.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/uva-lib:2230711 (accessed May 23, 2017).