Origins of Eugenics: From Sir Francis Galton to Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924

Sir Francis Galton. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society. [2.1]

ENLARGE

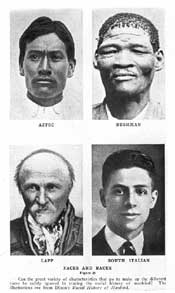

[2.2] Faces and Races, illustration from a eugenical text, Racial History of Mankind. Courtesy of Special Collections, Pickler Memorial Library, Truman State University.

[2.3] Harry H. Laughlin and Charles Davenport at the Eugenics Record Office. Courtesy of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

Positive and Negative Eugenics

Sir Francis Galton first coined the term “eugenics” in 1883. Put simply, eugenics means “well-born.” Initially Galton focused on positive eugenics, encouraging healthy, capable people of above-average intelligence to bear more children, with the idea of building an “improved” human race. Some followers of Galton combined his emphasis on ancestral traits with Gregor Mendel’s research on patterns of inheritance, in an attempt to explain the generational transmission of genetic traits in human beings.

Negative eugenics, as developed in the United States and Germany, played on fears of “race degeneration.” At a time when the working-class poor were reproducing at a greater rate than successful middle- and upper-class members of society, these ideas garnered considerable interest. One of the most famous proponents in the United States was President Theodore Roosevelt, who warned that the failure of couples of Anglo-Saxon heritage to produce large families would lead to “race suicide.”

Eugenics Record Office

The center of the eugenics movement in the United States was the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) at Cold Spring Harbor, New York. Biologist Charles Davenport established the ERO, and was joined in his work by Director Harry H. Laughlin. Both men were members of the American Breeders Association. Their view of eugenics, as applied to human populations, drew from the agricultural model of breeding the strongest and most capable members of a species while making certain that the weakest members do not reproduce.

Pedigree Charts, American Eugenics Society, and Fitter Families

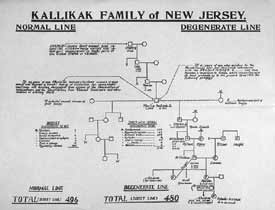

Eugenicists attempted to demonstrate the power of heredity by constructing pedigree charts of “defective” families. These charts were used to scientifically quantify the assertion that human frailties such as profligacy and indolence were genetic components that could be passed from one generation to the next. Two studies were published, “The Jukes”: A Study in Crime, Pauperism, Disease and Heredity by Richard L. Dugdale and The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness by Henry H. Goddard, that charted the propensity towards criminality, disease, and immoral behavior of the extended families of the Jukes and the Kallikaks. Eugenicists pointed to these texts to demonstrate that feeblemindedness was an inherited attribute and to reveal how the care of such “degenerates” represented an enormous cost to society.

The ERO promoted eugenics research by compiling records or “pedigrees” of thousands of families. Charles Davenport created “The Family History Book,” which assisted field workers as they interviewed families and assembled pedigrees specifying inheritable family attributes which might range from allergies to civic leadership. Even a “propensity” for carpentry or dress-making was considered a genetically inherited trait. Davenport and Laughlin also issued another manual titled “How to Make a Eugenical Family Study” to instruct field workers in the creation of pedigree charts of study subjects from poor, rural areas or from institutionalized settings. Field workers used symbols to depict defective conditions such as epilepsy and sexual immorality.

The American Eugenics Society presented eugenics exhibits at state fairs throughout the country, and provided information encouraging “high-grade” people to reproduce at a greater rate for the benefit of society. The Society even sponsored Fitter Family contests.

ENLARGE

[2.4] Kallikak family of New Jersey – Normal and Degenerate Lines

(enlarge to view additional eugenical pedigree charts). Courtesy of Paul Lombardo.

ENLARGE

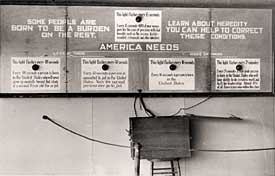

[2.5] Eugenics Display: Some people are born to be a burden on the rest. Learn about heredity: you can help to correct these conditions. American needs less of these, more of these. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

[2.6] Winners of Fittest Family Contest. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

Harry H. Laughlin and Acts of 1924: U.S. Immigration Act, Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act, and Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Act

[2.7] Harry H. Laughlin photograph. Courtesy of American Philosophical Society.

ENLARGE

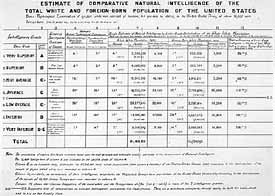

[2.8] Comparative Intelligence Chart. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

ENLARGE

[2.9] Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924

(enlarge to view additional Virginia legislative acts). Courtesy of Special Collections, Pickler Memorial Library, Truman State University.

In 1914, Harry H. Laughlin attended the first Race Betterment Conference, sponsored by J. H. Kellogg. The same year, in his Model Sterilization Law, Laughlin declared that the “socially inadequate” of society should be sterilized. This Model Law was accompanied by pedigree charts, which were used to demonstrate the hereditary nature of traits such as alcoholism, illegitimacy, and feeblemindedness. Laughlin asserted that passage of these undesirable traits to future generations would be eradicated if the unfortunate people who possessed them could be prevented from reproducing. In 1922 Laughlin’s Model Law was included in the book Eugenical Sterilization in the United States. This book compiled legal materials and statistics regarding sterilization, and was a valuable reference for sterilization activists in states throughout the country.

Proponents of eugenics worked tirelessly to assert the legitimacy of this new discipline. For Americans who feared the potential degradation of their race and culture, eugenics offered a convenient and scientifically plausible response to those fears. Sterilization of the “unfit” seemed a cost-effective means of strengthening and improving American society.

By 1924 Laughlin’s influence extended in several directions. He testified before Congress in support of the Immigration Restriction Act to limit immigration from eastern and southern Europe. Laughlin influenced passage of this law by presenting skewed data to support his assertion that the percentage of these immigrant populations in prisons and mental institutions was far greater than their percentage in the general population would warrant.

Laughlin also provided guidance in support of Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act, which made it illegal for whites in Virginia to marry outside their race. The act narrowly defined who could claim to be a member of the white race stating that “the term ‘white person’ shall apply only to such person as has no trace whatever of any blood other than Caucasian.” Virginia lawmakers were careful to leave an escape clause for colleagues who claimed descent from Pocahontas—those with 1/16 or less of “the blood of the American Indian” would also count as white.

The language of Laughlin’s Model Sterilization Act was used in Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Act to legalize compulsory sterilizations in the state. This legislation to rid Virginia of “defective persons” was drafted by Aubrey E. Strode, a former member of the Virginia General Assembly, at the request of longtime associate, Albert Priddy, who directed the Virginia Colony for the Epileptic and Feebleminded in Lynchburg, Virginia.