Resistance to Preventative Measures after the Spanish-American War

Immediately after the Spanish-American War Surgeon-General George Sternberg seemed to view the influence of what he termed its “sanitary lessons” as optimistically as he had once viewed that of Circular No. 1. In 1899, he predicted that the forthcoming publication of the Typhoid Board’s Abstract of Report on the Origin and Spread of Typhoid Fever would constitute “a most valuable contribution to the practical work of military sanitation.”

Soldiers’ Continued Recalcitrance to Typhoid Prevention Measures

Engraving of a medical examination. From The Story of the War of 1898 (1898) by William Nephew King, p.39

Many soldiers, however, demonstrated that they were as unimpressed by the Board’s post-war recommendations as by the Surgeon-General’s early-war guidelines. Although the rate for stateside typhoid-admissions per 1,000 soldiers dropped from more than 85 in 1898 to less than 6 in 1900, the latter figure nearly doubled in 1901 and remained high in 1902. Rising through 1901, the 1900 rate for stateside typhoid-deaths per 1,000 soldiers had likewise doubled by 1902. Although the impact of the 1902 statistics was softened somewhat by an awareness that they reflected greater diagnostic accuracy than those of previous years, it was exacerbated by the fact that both admission and mortality rates that year were worse for soldiers stationed stateside than for their countrymen stationed overseas.

Sternberg’s successors in the Surgeon-General’s Office soon encountered site-specific evidence that the Board’s work was often ignored. Shortly before Walter Reed’s death in 1902, he investigated a typhoid outbreak at Fort H. G. Wright, New York. In traveling spatially to Fort Wright, Reed also traveled temporally to late 1898, arriving amidst the predictable devastation wrought by infected soldiers. Reed then reconstructed a familiar history of exposed excrement, human contact, flies, and pathogen-conveyance to no less than three additional military installations.

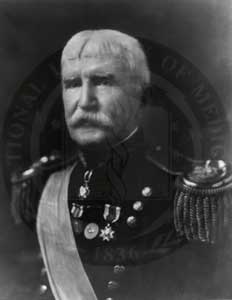

Robert M. O’Reilly. U.S. National Library of Medicine

In the wake of Reed’s work at Fort Wright, Surgeon-General Robert M. O’Reilly initiated the issuance of Adjutant-General’s Circular No. 62, presenting “in language simple enough to be understood by every enlisted man, rules of personal hygiene.” In 1905, however, new attacks by pathogen-carriers prompted O’Reilly to issue a circular letter to the Army’s chief surgeons, asking them to reiterate the importance of the “details of disinfection” to the medical officers under their supervision. Yet for the fiscal year spanning 1906 and 1907, O’Reilly reported typhoid’s presence in all the camps of instruction and a “decided increase” in its army-prevalence overall.

The attempts of the post-Sternberg Surgeon-General’s Office to instill discipline in people were accompanied by a reduced faith in the technical systems endorsed by Sternberg and the Typhoid Board. In 1905, O’Reilly concluded reluctantly that the “objectionable” privy-pits remained not only the sole means of waste-disposal at many stateside camps but also provided the sole practicable means of such disposal for troops engaged in practice marches and maneuvers. By that year he had also determined that the Forbes-Waterhouse Sterilizers were no less “objectionable” as soldiers refused to provide “the degree of care necessary to prevent them from becoming culture beds for bacteria.”

Civilians’ Continued Menace as Typhoid Carriers and Renewed Interest in Water

In his Report of 1908, Surgeon-General Robert O’Reilly noted that the War Department planned to expand dramatically the acreage devoted to “permanent maneuver camps.” The project lent new urgency to the search for prophylaxis that was “as perfect as possible.” Typhoid fever, he wrote, remained “the disease which in time of war most seriously threatens the efficiency of the Army.”

Jefferson Randolph Kean, who shared Walter Reed’s frustration with typhoid fever as well as assisting him in the triumph over yellow fever. From the Hench-Reed Collection, Historical Collections & Services, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, UVa

Contract Surgeon James Carroll and Major Jefferson R. Kean, allies of Walter Reed in the war on yellow fever, had in 1902 investigated a new typhoid outbreak in the Army’s Chickamauga, Georgia camp. The two surgeons traced the fever to the neighboring village of Rossville, where they found “unusually favorable conditions” for the disease. Surgeon-General O’Reilly reacted to the Carroll/Kean report with yet another indictment of dirty, indifferent civilians. As in 1898, the Army was “so exposed to typhoid fever that no matter how perfect the sanitation … an occasional case is unavoidable and in the majority of cases can be traced to a neighboring community.” O’Reilly concluded his warning by announcing the publication of what would become the 1904 edition of the Typhoid Board’s report. “The experience of the last few years,” he opined, “strengthens all the conclusions of the Board.”

Evidently, O’Reilly and Victor Vaughan determined that the Abstract of Report on the Origin and Spread of Typhoid Fever of 1900 lacked sufficient emphasis on water. For the edition of 1904, Report on the Origin and Spread of Typhoid Fever, Vaughan replaced Reed’s “Etiology” essay with appendices that focused solely on waterborne pathogens and offered more extensive and more statistical evidence than Reed’s essay. Publication of the 1904 edition coincided with a surge of typhoid articles in the popular press, coverage that shifted prescriptive emphasis from personal discipline to broad prophylaxis through political reform and improved waterworks and sewers.

Civilian pathogen-carriers in Washington, D. C. lost little time in mocking the renewed attention to water. Typhoid rates that had long hovered at endemic levels assumed epidemic proportions there in 1906. Compounding the embarrassment created by such conditions in the nation’s capital and the Surgeon-General’s headquarters city, the Army’s Corps of Engineers had overseen installation and activation of a state-of-the-art water filtering plant for Washington in 1905. By 1908, investigators concluded that personal contact and inadequate disinfection of typhoid patients’ excrement had largely negated the city’s adequate sewers and new waterworks.

Through a series of articles in 1907-1909, Mary “Typhoid Mary” Mallon provided a specific, nationally recognized face for the phenomenon of contact-infection. She personified no less than three concepts identified by the Typhoid Board: the civilian carrier, the recalcitrant carrier, and the chronic carrier. Ironically, Victor Vaughan may have inadvertently accentuated Mary Mallon’s novelty and consequent impact. In excising Reed’s “Etiology” essay before issuing the 1904 Report, he also excised most of the Board’s discussion of the chronic-carrier state.