English Caricature: Quacks & Nostrums

Many nineteenth-century patients grew tired of the inefficacy and cost of medical treatment by orthodox physicians and readily turned to the swarms of “irregular” practitioners of medicine that filled the British countryside. Physicians denounced such “irregulars” as quacks and charlatans, but people, desperate for relief and respite from disease and affliction, easily succumbed to the slick advertisements and grandiose claims of quack medicine. Quack doctors and their nostrums, along with a public that believed in them and their cures, became favorite subjects for the satirist. The artists poked fun of the highfalutin claims of the quacks’ cure-all remedies and the gullible consumers who were duped by them.

Quack doctors cloaked themselves and their cures in an aura of respectability. Many quacks were not the necessarily ill-bred, uneducated, ignorant, or inept imposters the satirist wished to portray. Some possessed formal training (or even had a diploma in medicine) and had a vast array of experience in treating illness. They also appealed to the general public because they “championed novelty” in their products during an age of science and technology. Finally, the quacks successfully promoted themselves through self-advertisement, particularly by publishing tracts and flyers and taking out classified advertisements.15

Perkins Patent Tractors

One of the more popular new-fangled treatments in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was the Perkins Patent Tractors. Their creator, Elisha Perkins (1741-1799), attended Yale University and was a physician in Connecticut. Drawing upon experiments done with “animal electricity” by an Italian scientist Luigi Galvani, Perkins theorized that redirecting the body’s natural electricity could draw out pain and disease. In a furnace at his home, Perkins fashioned brass and iron rods measuring about four inches. The rods had one flat side and one round side with one blunt end and one pointed end. The practitioner held the rods in his hand and rested the point of the rods on the skin. Then he stroked or drew the tractors over the unhealthy area of the body to attract and draw out affliction.

Perkins’s son, Benjamin, a Yale graduate, moved to London, England to promote his father’s amazing invention. He set up shop at No. 28, Leicester Square, the former home of the famed father of scientific surgery, John Hunter. (Perkins mentioned this fact in his advertisements to add further credibility to his magical product.) In a May 1801 advertisement in The Times, Perkins charged “5 guineas” for the tractors, which he claimed worked “600 cures.”16 In November of that year, James Gillray published an amusing print entitled, “Metallic Tractors,” that demonstrated his “enduring contempt for humbugs and publicity seekers.”17 It appears that Perkins found great satisfaction in the caricature, as he wrote a thank-you note to Gillray and requested the print be exhibited in other shops. Any publicity was favorable publicity. By this time, however, the popularity of Perkinism was waning. A tract published in 1800 declared that in a scientific study by Dr. John Haygarth wooden tractors produced as many cures as metallic tractors.18

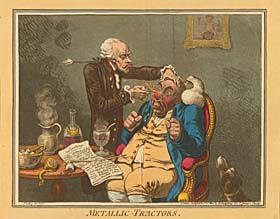

Metallic-Tractors. James Gillray, published by H. Humphrey, 27 St. James’s Street, London, November 11, 1801.

In this particularly amusing cartoon, James Gillray comments on the lengths people will go to cure affliction, even enlisting the aid of well-known quacks. In this case the patient suffers from a severely reddened and bulbous nose. The picture drawn behind the man is of a cherub straddling a barrel while holding a glass in one hand and a bottle in the other. On the table is a bottle of brandy—perhaps a commentary by Gillray that alcohol consumption contributed to the patient’s rhinophyma.

The patient has succumbed to the lure of the advertisements of the famed Benjamin Perkins in the local newspapers. The paper on the table states, “just arrived from America, the Rod of Aesculapius. Perkinson in all his Glory—being a certain Cure for all Disorders, Red Noses, Gouty Toes, Windy Bowels, Broken Legs, Hump Backs. Just discover’d, the Grand Secret of the Philosopher’s Stone with the true way of turning all Metals into Gold. Pro bono publico.”

Gillray’s practitioner is a sinister fellow—the man’s braid juts out like a devil’s tail. He sticks one tractor in his mouth, freeing up both of his hands. One hand holds onto the patient’s head, pushing off the man’s wig to reveal a completely bald head. The other hand directs electricity through the tractor onto the man’s red bulbous nose. Flames spurt out of the patient’s nostrils and nose. The patient grips his hands in tight fists and clenches his teeth, demonstrating that the treatment is painful.

Morison’s Vegetable Pills

One of the most famous, controversial, and successful “quack” doctors in nineteenth-century England was James Morison (1770-1840). He appealed to the general public because of the missionary-like zeal in which he opposed “orthodox” medicine; in particular, he attacked physicians’ excessive fees and toxic medicine. Like other well-known quacks, he organized his own medical school choosing the conservative and respectable name, The British College of Health. So, in contrast to regular doctors, he named his practitioners “hygeists.” In the Hygeian system, Morison wrote, “all maladies arise from impurity of the blood, though they may show themselves under various forms.”19 The only cure to this imperfect and impure circulation of the blood was his very own Morison Vegetable Pills. The purgation by vegetable pills—a laxative made from aloes, jalap, gamboges, colocynth, cream of tartar, myrrh, and rhubarb—was the only effectual mode of eradicating disease. Morison felt that the stomach and the bowels could not be purged too much, and it wasn’t uncommon for “hygeists” to recommend 15 or 20 pills at the onset of illness. Caricaturists responded to Morison’s hyperbole and the public’s gullibility by creating more than 25 prints about Morison Vegetable Pills.20

Medical professionals vigorously attacked James Morison. A physician writing an editorial in the British medical journal, Lancet, wrote Morison was guilty of “fraud and extortion” and his Vegetable Pills were “active poison.”21 The founding editor of The Lancet, Thomas Wakley, spent over a decade trying to discredit Morison’s theories. Physicians worried that unnecessary deaths were caused by the use of his medicines. In 1836 a vendor of Morison Vegetable Pills actually was convicted of manslaughter of a patient diagnosed with rheumatism in the knee. A post-mortem examination left no doubt that the “large and excessive quantities of pills” doled out by the “hygeist” resulted in the fatality.22

Extraordinary Effects of Morrisons Vegetable Pills, Grants Oddities No. 1. Charles Jameson Grant, published by J. Kendrick, 54 Leicester Sq, London.

In this caricature by Charles Jameson Grant, two men discuss the remarkable ability of Morison Vegetable Pills to regenerate legs. The men are dressed in well-worn, patched clothes and sport unshaven faces. (Clearly a comment by the artist that the lower classes were particularly naïve.) The individual on the right uses crutches and has wooden legs strapped to his stumps. The other character, with two fine strong legs, carries wooden legs under his arms. The conversation goes as follows:

Vy Snook is that you! Vell if I arnt completely Struck! Vy Ven did you change your Vooden legs for Cork ‘uns!…?

Cork ones! now do they look like a Pair of Cork ones. No old Boy they are real Flesh and Blood, and ten times a Better Pair than wot I was Born with. it’ll only cost you a Shilling my Tulip and you’ll have as good a Pair of Stumps as myself. Yesterday you must know, I bought a Box of Morrisons Uniwersal Wegetable Pills, for a Swelling in my Thighs. well, so I took’em all afore I went to Bed and when I awakes in the morning to kick of the clothes. I’m bless’d if I did’nt find myself with these ‘ere couple of Jolly good Legs and my Old Wooden ones right at the bottom of the Bed!!!