Medicinal Springs of Virginia in the 19th Century

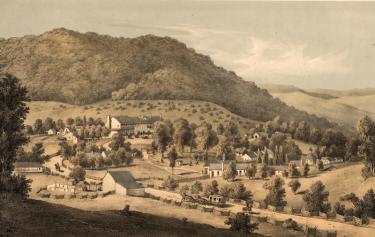

Edward Beyer’s print of Hot Springs from the Merritt T. Cooke Memorial Virginia Print Collection, 1857-1907, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

The title page to Burke’s 1846 edition of The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia which has been scanned in its entirety and is part of the University of Virginia digital text collection. {1}

This exhibit showcases a number of original nineteenth-century letters and documents, housed in Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, that relate to the 11 springs (Warm, Hot, Sweet, Red-Sweet, White Sulphur, Red Sulphur, Salt Sulphur, Blue Sulphur, Daggers’ or Dibrell’s, Rockbridge Alum, and Fauquier White Sulphur) that Dr. William Burke wrote about in the second edition of his book, The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia. Dr. Burke’s book was entered into the Clerk’s Office of the District Court for the Southern District of New York in 1842 and published in 1846, four years after the first edition. This is the first book purchased with the Weaver Family Endowed Rare Book and Medical Materials Fund, created in honor and memory of Edgar Newman Weaver, M.D., Evelyn Richards Weaver, and David Delmar Weaver, M.D., by Margaret Carr Weaver Crosson, Evelyn Dabney Weaver Dwyer, and Edgar Newman “Wink” Weaver, Jr., M.D. The book is housed in Historical Collections, The Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

William Burke, whose book provides the starting point for this exhibit, was the owner of Red Sulphur Springs in what is now Monroe County, West Virginia. He first visited these springs in 1829 as an invalid. He purchased them in 1832 and transformed the property both by replacing the small, windowless cabins with spacious and conveniently arranged buildings and also by removing trees to permit the sun to reach what had previously been a gloomy gorge. According to Henry Huntt who recorded his visit to the Red Sulphur in 1837, the servants were “prompt and obedient,” and the dining table was “abundantly supplied with every variety of viands that can tempt the appetite.” {Huntt, 19} In The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia, Burke writes that he “surrendered possession of the property by a deed or contract recorded in the County Court of Monroe,” moved to Richmond, and in early 1842 divested himself “of every residuary interest in the estate.” {Burke, 169} While no longer an owner by the time his second edition was published in 1846, it is clear that he continued to have ties to these springs, and he gave precedence to the Red Sulphur in his book, devoting more than one third of The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia to this particular spring.

The title of Burke’s 1853 edition, The Virginia Mineral Springs, allowed him to include springs from all of Virginia not just the western part. {2}

Dr. Burke also wrote The Mineral Springs of Virginia. The preface to his first edition, published in 1851, states that he chose to re-write his first book and issue it as a new work. He admits, “In the course of the former publications, I became involved in controversies and personalities, as foreign from my taste and disposition as they were uninteresting to the public. These and other irrelevant matters I have discarded from the present work.” Indeed, his main antagonist in his first book is Dr. J. J. Moorman, a fellow author and resident physician at the White Sulphur Springs. Ten percent of Dr. Burke’s 1846 volume, The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia, is devoted to his disagreement with Dr. Moorman concerning the effectiveness of White Sulphur Springs’ water that no longer contained “sulphuretted hydrogen gas.” Inflammatory statements present in Burke’s first book are removed from his reworked 1851 volume. For example, this caustic 1846 assessment of Dr. Moorman is excised: “His facts are without foundation in truth; his arguments puerile and shallow; his theories untenable; his absurdities ridiculous; his motives palpable and culpable; and his efforts to bolster up a selfish practice, a gross imposition.” {Burke, 172} With a second edition of The Mineral Springs of Virginia, newly titled The Virginia Mineral Springs, in 1853, Burke was able to do what he had hoped to do in the first edition. He visited the eastern group of the Virginia springs and included chapters on Jordan’s White Sulphur, Shannondale, Berkeley, Orrick’s Sulphur, and Capon Springs as well as inserted additional information on springs written about earlier.

Dr. Burke was married and had at least one daughter and one son. Grace Fenton Hunter visited the Red Sulphur Springs for over a month in 1838 and mentioned Dr. B., presumably Dr. Burke, and Mrs. Burke a number of times in her diary. Hunter described Mrs. Burke, with whom she exchanged numerous visits, as a “kind” and “sensible woman, talkative, and more agreeable than the generality of persons.” She also wrote that Mrs. Burke and her daughter played music and sang. In the introduction to his small book, Red Sulphur Springs, Monroe County, Virginia, published in 1860, Dr. Burke stated that the professional experience at the Red Sulphur of his son, Thomas J. Burke, totaled 18 years. William Burke was still visiting the establishment in the late 1850s as Red Sulphur Springs has several testimonial letters that placed the writers and Dr. Burke at these springs in the summer of 1859.

As William Burke makes clear, the Virginia springs were a destination for both the invalid and the vigorous. Some sought healing from an array of diseases. Every malady from indigestion and bronchitis to consumption, paralysis, and “diseases peculiar to females” had its sufferers seeking a cure by “taking the waters.” Dr. Burke expounds on the incongruity of the juxtaposition of those desperately seeking a restoration of health and those at the springs for the sake of entertainment or socializing. “The invalid, pale, emaciated, and wretched, may be seen there at almost every hour, waiting till the giddy dance of the gay and volatile, who came there merely to gratify ‘a truant disposition,’ shall leave the waters free for him to drink and be healed. The feverish flush, the hectic of consumption, the tottering gait of rheumatism, the wasted form of the dyspeptic, may all be observed in contrast with the ruddy glow of manly health, the free elastic step of youthful vigor, the gay smile of unpained hearts, and the loud laugh of mirth that knows not even the check of another’s sufferings.” {Burke, 1846, p. 133}

Reputable physicians attested to the healing aspects of the various mineral waters. Thomas D. Mütter, Chairman of the Department of Surgery at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia called the Salt Sulphur “one of the most valuable of our remedial agents” in a range of diseases. {Mutter, 19} Henry Huntt, a personal physician to Presidents James Monroe, John Q. Adams, and Andrew Jackson, extolled the virtues of Dr. Burke’s Red Sulphur Springs. Drs. James L. Cabell and John S. Davis, both Professors in the medical school at the University of Virginia, gave an endorsement for the mineral water from Rockbridge Alum Springs as useful in myriad diseases. Cabell, also a resident physician at the Hot Springs, authored a treatise on the value of the thermal baths on disorders as varied as deafness and rheumatism. Dr. William Beverly Towles, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Virginia, cared for patients at the Hot Springs as evidenced by his Case Book for 1885.

The letters from Special Collections reflect a range of spring experiences and expectations. Written to family and friends they probably give a more truthful assessment of the waters than the resident physicians and property owners or the testimonials they solicited. Some of the letters are very encouraging. Burl Fretwell writes that he brought a woman, probably his wife, home from the Alum Springs, and a cough of two years duration had finally cleared up. John McLaughlin attests to the benefits of the springs and says his health is better than it had been for many months. James D. Wood, writing from his third spring in three weeks, declares that his general health is “greatly improved.”

Other writers are hopeful but describe mixed results in terms of their health at the springs. Randolph Harrison thought he was recovering at the Alum Springs, but then came down with a fever that “took all the starch out of me.” After spending a month at the Red Sulphur, Grace Fenton Hunter writes in a letter that she has “gained flesh, and also strength,” but her diary entry for the same day states that she “read and worked as usual, but feeling badly did little of either.” R. T. Hubard at the White Sulphur corresponds with his wife indecisively, “I spent one week at the Sweet Springs and returned here yesterday morning. The Sweet Spring water & bath improved my health, I think, a little, tho not much. Indeed I fear that my health will not be greatly improved by my trip.” J. S. Martin writes, “I had perceived no benefit (or very little) from the Water here.” His letter from White Sulphur mentions hope four times, including, “I feel that I shall improve now & hope my next [letter] may be more cheerful.”

Some correspondents realize their health has definitely not improved at the springs. John Minor feels worse at the Hot Springs and considers himself to be “much weaker & more reduced than I ever was before.” Edmund Randolph tries the Warm Springs for his paralysis to no avail. Till enjoys the baths at the Warm Springs but asks a granddaughter of Thomas Jefferson about the pain in her breast, says she herself suffers from it, and declares, “I was not improved by my excursion, I have been sick almost constantly since I came home and my cough is worse than it ever has been. Sometimes I think, at least I am afraid that I am quite in bad health.”

Thomas Jefferson’s visit to the Warm Springs in August 1818 covers a wide range of experiences. He describes the bath as “delicious” and within a week calls the spring with the Hot and Warm “of the first merit.” He also presumes that the “seeds of his rheumatism” are “eradicated.” But the passing of another week brings an alarming occurrence. He tells his daughter, “I do not know what may be the effect of this course of bathing on my constitution; but I am under great threats that it will work it’s effect thro’ a system of boils.” Indeed, he claims that he suffers “prostrated health from the use of the waters” with abscesses, fever, sweats, and extreme debility. In December his summer visit still finds its way into a letter, “my trial of the Warm springs was certainly ill advised. for I went to them in perfect health, and ought to have reflected that remedies of their potency must have effect some way or other. if they find disease they remove it; if none, they make it.”

Many who went to the baths were not seeking improvement in their health but visited to enjoy various amusements that included gaming, drinking, dancing, carriage rides, horseback riding, and ten-pin alleys. This is reflected in the receipts for White Sulphur Springs in 1860 showing substantial sums collected for the bar and the shooting gallery. Some hoped to meet their future spouse while enjoying the waters. R. T. Hubard upon seeing Randolph Harrison at the White Sulphur Springs suspects Harrison is “in pursuit of a wife.”

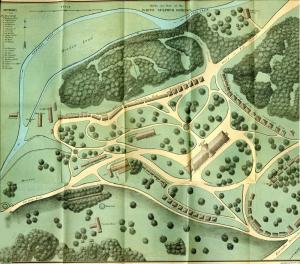

Dr. Moorman’s birds-eye view of White Sulphur shows the romantically named walking paths and lists the names of 20 people who had their own cottage. {4}

This birds-eye view of the White Sulphur, published in 1859, shows the location of the bath house and several springs, but also the winding paths through the grove of trees south of the creek with names such as Lovers Walk, Lovers Leap, Lovers Rest, Way to Paradise, Courtship Maze, Acceptance, Rejection, and Hesitancy. Elizabeth Noel attests to the flaunting display of the guests at the White Sulphur when she writes her daughter, “I was in the parlor one night, it gave me the ache to see so much promenading, & so much finery … The bell[e] of the place is a Mrs. Vivian from the south, she dresses very fine, but dont wear hoops, there is every kind of dress & ever[y] kind of fashion here.

James D. Wood declares in a letter that the Red Sweet Springs is an “exceedingly pleasant place” where his party has “made many pleasant acquaintances” and “had an agreable trip.” Other visitors found the social scene at the springs less than satisfactory. John Minor writes from the Hot Springs about suffering “solitary & alone cooped up in a little room 10 feet square.” In her private diary, Grace Fenton Hunter declares, “Nothing could be more monotonous than the time spent here,” and indicates she is bored at the Red Sulphur with the “same routine of walking to the spring, working a little, talking a little, or rather a great deal, frequently reading a little, and speaking to passing acquaintances.” R. T. Hubard informs his wife from the White Sulphur that in spite of the presence of the President [Martin Van Buren] of the United States and other eminent men, he finds the place “as dull and uninteresting to me as possible.”

Hubard describes the Virginia springs as not only dull, but also offensive and perilous. He calls the White Sulphur “that sink hole of extravagance, gambling & vice for many young & unmarried men.” He hopes his sons will only go the springs for their health and that “Heaven in its mercy” will “guard & defend them from all the evil, the seductive & corrupting influences of those dull, disagreeable and dangerous places.” Thomas Jefferson was disappointed to find “little gay company” at Warm Springs in 1818 and expected to “pass a dull time.” When he decided to yield to the general advice of a three week course, it was not because he was enjoying himself. Rather, he wanted “to prevent the necessity of ever coming here a 2d time,” because “so dull a place, and distressing an ennui I never before knew.”

Proprietors of the springs realized that the difficulty of travel to remote locations hampered their business. In 1818 Thomas Jefferson described being “aggravated by the torment of long & rough roads.” Twenty years later Grace Fenton Hunter wrote that her companion, “is just getting over the fatigue of the journey, which was enough to make a well person sick, much more invalids.” In the first half of the nineteenth century, dirt roads or trails were replaced by plank roads and paved roads. Carriages and stage coaches supplanted the necessity of arriving on foot or horseback. By mid century railroad lines headed west with the result that many springs could be reached by rail and then a short journey by stage.

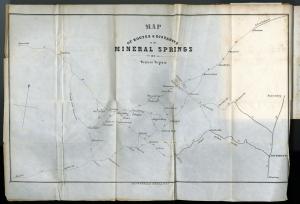

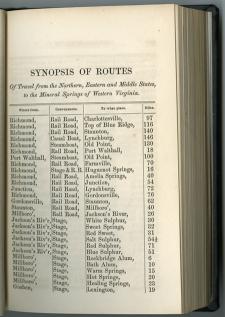

Like other mid-nineteenth-century books about the springs, Dr. Burke’s second edition of The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia includes a map of routes and distances to the various establishments from other parts of Virginia as well as between the various springs themselves. It was important to show how one would get from one spring to another as visitors often went to more than one, seeking a change in venue or eager to try waters credited with different advantages, depending on temperature and chemical analysis. John McLaughlin’s letter written in the summer of 1814, when travel would have been difficult, mentions his time at the White Sulphur, Hot, and Warm Springs, and declares his intention to visit the Sweet Springs. Grace Fenton Hunter spends six weeks at the Red Sulphur after making stops at the White Sulphur, Warm, Hot, and Salt Sulphur Springs.

Dr. J. J. Moorman’s book, The Virginia Springs, gives a synopsis of travel routes within Virginia and slightly beyond. He includes not only distances but also the methods of conveyance: railroad, stage, canal boat, and steamboat. Thomas Jefferson also compiled his own personal mileage chart from Staunton to Warm Springs and rated taverns and inns along the way as very good, middling, or very bad. Several received a very good ranking with the caveat “if sober.”

The Civil War had a devastating effect on the springs. Instead of being locations for a summer retreat in the mountains, they were often sites of destruction. Dr. J. H. Hunter was appointed Inspector of Hospital Property at The Hot, Warm and Healing Springs in December 1861 and was instructed to report on damaged, missing, and stolen property. Occupied by both armies, some of the buildings at Fauquier White Sulphur Springs were damaged or destroyed by shelling. Pell Manning writes about fighting around those Springs and states that the hotel once able to accommodate 3000 people was “one mass of ruins ‘from turret to foundation stone.’” All that was left of the Blue Sulphur Springs after the conflict was the pavilion over the springs.

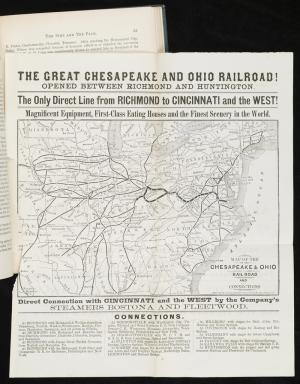

The Great Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad! This 1873 pronouncement shows the White Sulphur Springs’ depot. Its places of interest include six more springs in Burke’s book reachable by stage coach. {7}

Some of the resorts never recovered from the war while others took years to wade through the resultant financial upheaval. The Hot Springs was the subject of a case in the Circuit Court of Albemarle a decade after the 1858 death of the owner, Dr. Thomas Goode. Being “unproductive, deserted, far off from the world and the military centres, in a valley open to military raiders, deserters and stragglers” the property was sold by Goode’s executors for less than its debts. The University of Virginia Library has numerous White Sulphur Springs documents concerning liens, debts, creditors, and failed Confederate bonds. G. W. Lewis wrote about the insolvent condition of White Sulphur in February 1867 and its deleterious effect on the estate of Robert Wormeley Carter. Jeremiah Morton, a Director of the White Sulphur Springs Company, solicited help from the federal court in October 1873 as the property had nine liens on it and had sold all its furniture and stock on hand in 1861 for confederate bonds which proved a total loss. However, the White Sulpher Springs was the beneficiary of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway as it was the only spring that could claim direct rail service with the first train arriving in 1869.

The twenty-first century finds the eleven springs written about by Dr. Burke in vastly different conditions. The White Sulphur Springs and the Hot Springs are the Greenbrier and Homestead resorts respectively. Both are luxury vacation destinations with three championship golf courses and elegant accommodations. The Warm Springs, now called the Jefferson Pools, are part of the Homestead and offer the same rustic bathing that Thomas Jefferson experienced in 1818. The men’s bath house is the oldest spa structure in Virginia and the one Jefferson used. The Rockbridge Alum Springs complex is a Young Life summer camp. The Red Sweet, Salt Sulphur, and Sweet Springs all have structures that have survived in various states of repair. Plans to restore the buildings at Sweet Springs and reopen as a resort have been halted. One guest house can be rented at Salt Sulphur.

Of the Blue Sulphur, only the Grecian temple pavilion remains. The structures associated with the eight springs just mentioned are on the National Register of Historic Places. The Fauquier Springs Country Club is located on the site of the old Fauquier White Sulphur Springs. No buildings are left at Dagger’s Spring. This is also true of Dr. Burke’s beloved Red Sulphur whose buildings were torn down during or after World War I. See the Springs in a Google map with recent photos.

Image Credits:

- {1} William Burke, The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia, New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1846: title page. Historical Collections & Services, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

- {2} William Burke, The Virginia Mineral Springs, Richmond: Ritchies & Dunnavant, 1853: title page. Historical Collections & Services, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

- {3} Thomas D. Mütter, The Salt Sulphur Springs, Monroe County, Virginia, Philadelphia: T.K. & P.G. Collins, 1840: title page. Historical Collections & Services, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

- {4} John J. Moorman, The Virginia Springs, and Springs of the South and West, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1859: facing title page. Historical Collections & Services, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

- {5} William Burke, The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia, New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1846: facing title page. Historical Collections & Services, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

- {6} John J. Moorman, The Virginia Springs, Richmond, Va.: J. W. Randolph, 1857: p. xv. Historical Collections & Services, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

- {7} N. J. Watkins, ed., The Pine and the Palm Greeting, Baltimore : J. D. Ehlers’ & Co.’s Engraving and Printing House, 1873: fold out between pages 52 and 53, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

Sources:

- William Burke, The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia, New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1846.

- William Burke, The Mineral Springs of Virginia, Richmond: Morris & Brother, 1851.

- William Burke, Red Sulphur Springs, Monroe County, Virginia, Wytheville: D. A. St. Clair, Printer, 1860.

- William Burke, The Virginia Mineral Springs, Richmond: Ritchies & Dunnavant, 1853.

- Henry Huntt, A Visit to the Red Sulphur Spring of Virginia, during the Summer of 1837, Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1839.

- Thomas D. Mütter, The Salt Sulphur Springs, Monroe County, Virginia, Philadelphia: T.K. & P.G. Collins, 1840.