Cuban soldiers fighting Spain in the Cuban War of Independence. Strohmeyer & Wyman, “Cubans in their Trenches”, circa 1899. Digital image courtesy of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98518183/.

Cuba Struggles for Freedom from Spanish Control

When the United States and Spain formed the yellow fever commissions of 1878, Cuba was just beginning to recover from a devastating war that killed an estimated 200,000 and wrecked the island’s plantation economy. The conflict, known as the Ten Years’ War (1868-1878), only came to an end when the Spanish government and the Cuban separatists recognized that neither side would achieve a complete victory and that peace would only come through negotiation.[1] The resulting treaty, the Pact of Zanjón (1878), brought temporary peace, but Spanish concessions in the agreement failed to appease the most dedicated freedom fighters. Initially, die-hard separatists failed to generate sufficient support from the Cuban people to continue the fight for independence. However, over the next 17 years, Cuban discontent with Spanish rule grew once more as it became clear to many Cubans that peace would not solve persistent social, political, and economic problems in the colony. When a trade dispute between Spain and the United States caused an economic crisis in Cuba, this growing discontent erupted into small uprisings. [2]

The Cuban War of Independence began in 1895 when exiled separatist leaders returned to the island and organized the uprisings into a revolutionary movement. Small groups of separatist troops successfully harassed Spain’s large colonial army, but they lacked the resources and manpower to force a quick surrender. Both sides, frustrated by defeats, committed atrocities against civilians and soldiers to gain advantages in the conflict. The most infamous atrocities in the conflict resulted from the Spanish practice of “reconcentration” — a systematic campaign to forcibly relocate Cuban civilians into concentration camps. By the end of the Cuban War of Independence, perhaps as many as 170,000 civilians in the camps, or around 10% of the population, died of starvation, disease, and violence. [3] After 3 years of war, severe measures failed to provide either side with a decisive victory. Separatist fighters killed up to 10,000 Spanish soldiers and disease killed another 41,000, but the separatists were still unable to dislodge the Spanish from their strongholds or generate overwhelming support from the Cuban people. [4]

The United States Considers Intervention in Cuba

In the 19th century, Cuba and the United States developed a close, complex relationship. Although Cuba was a colony of the Spanish Empire, many Americans and Cubans believed that the island naturally belonged within the U.S. sphere of influence. Cuba’s culture and society became increasingly intertwined with its northern neighbor, and by the end of the 19th century, the United States would become Cuba’s most important economic partner. [5] At the outbreak of the Cuban War of Independence, because of the close ties between the United States and Cuba, there was a heated debate in the United States about the country’s role in the conflict. At first, it was the policy of the Grover Cleveland and William McKinley administrations to recognize Spanish rule over Cuba and prevent the flow of private U.S. aid to the Cuban separatists. [6] However, some Americans criticized this approach and strongly advocated for a more aggressive role in the war. Among these Americans was an influential group that were popularly known as jingoes. They believed that it was the destiny of the United States to become an imperial power and argued that the nation needed to maintain a strong military and expand overseas to secure its borders and ensure economic prosperity. Jingoes also argued that an empire was “the white man’s burden”—an obligation to dominate non-European peoples and spread U.S. ideas, customs, and values across the globe. [7] For this constituency, intervention in Cuba would keep the island within the U.S. sphere of influence and was an important step toward building a new empire. [8] Reports in U.S. newspapers of Spanish atrocities, particularly the reconcentration program, shocked many Americans and made them more receptive to arguments for intervention. Americans who before had not been attracted to imperialism, came to believe that intervention was now necessary for humanitarian reasons. They also saw parallels between the Cuban struggle for Independence and their nation’s own revolutionary origins. [9]

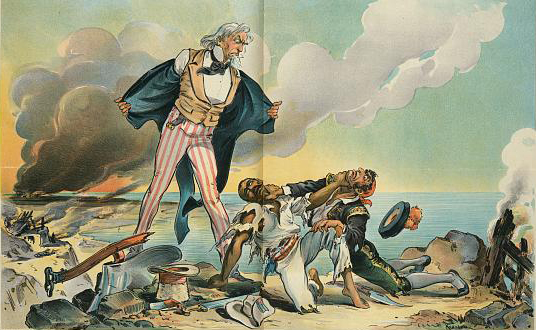

This editorial cartoon titled, “The Peace Maker”, illustrates the attitudes of many Americans toward the Cuban War of Independence and the need for U.S. intervention after the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine. Keppler, U.J. “The peace maker.” Puck, volume 43, no. 1102, April 20, 1898. Digital file courtesy of the Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012647557/.

The United States Declares War on Spain after the U.S.S. Maine Is Sunk in Cuba

The McKinley administration resisted public pressure to intervene until the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine. In January 1898, the United States sent the battleship to Havana to protect U.S. interests in Cuba. Three weeks later, a mysterious explosion aboard the ship sunk it and killed over 260 men. Although investigators at the time failed to determine the cause of the explosion, U.S. newspapers blamed Spain and inflamed the U.S. public. In April 1898, public opinion moved Congress to declare war on Spain and the United States entered the Cuban War of Independence as part of the broader Spanish-American War. [10] Cuban separatists had mixed reactions to the U.S. intervention. Many welcomed it as the best hope for victory over Spain. However, separatists also feared that the United States would use the intervention as an excuse to make Cuba a U.S. protectorate or colony. [11] Cuban separatists became particularly worried about U.S. intentions when it became clear that the United States was generally not interested in coordinating their military operations with the separatists at the outset of the intervention. [12] Participation in the war was short and relatively bloodless for the United States. After only 3 months, U.S. expeditionary forces decisively defeated weakened Spanish troops in Cuba and seized Spanish possessions in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean. Spain quickly sued for peace. Under the resulting peace treaty it ceded Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to the United States and it relinquished its claims over Cuba. However, Cuba would not gain its independence. Under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1898), Cuba became a protectorate of the United States and the U.S. military would remain in Cuba to govern the island until the federal government believed that the Cuban people were “ready” for independence. [13] ”Sources“