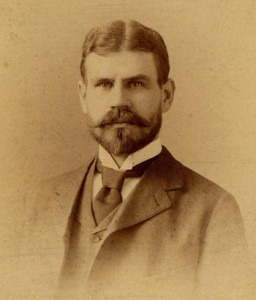

Portrait of Jesse Lazear, 1896. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995, Box-folder 79:25, Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

Jesse William Lazear was a physician who was a member of the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission in 1900. Lazear’s death from yellow fever at the outset of the commission’s work in Cuba would lead to his elevation as a martyr for medical science in the eyes of many during the twentieth century.

“I rather think I am on the track of the real germ,” Jesse W. Lazear wrote his wife from Cuba on September 8, 1900. [1] Seventeen days later, the fulminating case of yellow fever Lazear had contracted just over a week after writing Mabel H. Lazear suddenly ended the young scientist’s life. He was 34 years old. Unlike so many other yellow fever fatalities, however, this one would lead to a direct and highly successful assault on the disease itself. Yellow fever’s ascendancy, endemic in Cuba, was about to be undermined.

Lazear had reported to Camp Columbia, Cuba in February 1900 for duty as an acting assistant surgeon with the U. S. Army Corps stationed on the island. Here he undertook bacteriological study of tropical diseases, particularly malaria and yellow fever, and in May he was named to the Army board charged with “pursuing scientific investigations with reference to the infectious diseases prevalent on the island of Cuba.” [2]

These orders placed him officially in the company of Walter Reed, James Carroll, and Aristides Agramonte — the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission — though Lazear had already met Reed the preceding March on a project to evaluate the efficacy of electrozone, a disinfectant made from seawater collected off the Cuban coast. While Reed was in Cuba that March, Lazear discussed with him the recent discovery of British scientist Sir Ronald Ross concerning the mosquito vector for malaria. At Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where he was first a medical resident and later in charge of the clinical laboratory, Lazear had followed Ross’s accomplishments with great interest, and pursued field work and experimentation on the Anopheles mosquito with fellow Hopkins scientist William S. Thayer. Lazear was thus the only member of the Commission who had experience with mosquito work, and was consequently the most open to the possible verity of Cuban scientist Carlos Juan Finlay’s theory of mosquito transmission for yellow fever.

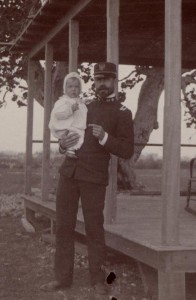

Jesse W. Lazear with Houston Lazear (his son) in Cuba, 1900, Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995, Box-folder 79:40, Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

The record is apparently silent as to when Lazear first visited Finlay. Certainly by late June Lazear was beginning to grow mosquito larvae acquired from Finlay’s laboratory, the first specimens brought to him by Henry Rose Carter, of the United States Public Health Service. [3] Not long after arriving in Cuba Lazear met Carter, whose own observations on yellow fever strongly suggested an intermediate host in the spread of the disease. However, Army Surgeon General George Miller Sternberg, who organized the Yellow Fever Commission, first charged the board members to investigate the relationship of Bacillus icteroides to yellow fever — proposed by the Italian Scientist Giuseppe Sanarelli as the actual cause of the disease. “Dr. Reed had been in the old discussion over Sanarelli’s bacillus and he still works on that subject,” Lazear wrote his wife in July, “I am not all interested in it but want to do work which may lead to the discovery of the real organism.” [4] Soon he would have the opportunity. The relatively quick failure of the Bacillus icteroides inquiry opened the door to what became the ground-breaking mosquito work, and Lazear was well placed to begin.

The project started in earnest on August 1, 1900. In a small pocket notebook Lazear noted the preparatory work of raising and infecting mosquitoes, and subsequently recorded the series of eleven experimental inoculations made from the 11th to the 31st of August, the last two producing cases of full-blown yellow fever. These two positive cases developed from mosquitoes allowed to ripen over a period of 12 days, and this was Lazear’s crucial discovery. The epidemiological pattern was thus entirely consistent with Carter’s observations of a delay between the primary and secondary outbreaks of yellow fever in an epidemic, and, in addition, explained why Finlay’s experiments had been largely unsuccessful — he had not waited long enough before inoculating his subjects.

Although Lazear never directly admitted to experimenting on himself, when Reed reviewed Lazear’s sketchy notations he evidently found entries strongly suggesting Lazear’s case was not accidental, as officially reported. Unfortunately, the little notebook so crucial to the preparation of the Commission’s famous initial paper, The Etiology of Yellow Fever — A Preliminary Note [5], vanished from Reed’s Washington office after his own untimely death in 1902. Still, Lazear’s invaluable contribution to the Commission’s victory was widely recognized and elicited tributes from many quarters: “He was a splendid, brave fellow,” Reed said of his young colleague, ” and I lament his loss more than words can tell; but his death was not in vain- His name will live in the history of those who have benefited humanity.” [6] “His death was a sacrifice to scientific research of the highest character,” stated General Leonard Wood, military Governor of Cuba. [7] “Your husband was a martyr in the noblest of causes,” Dr. L. O. Howard wrote to Mabel Lazear, “and I am proud to have known him. . . . His work contributed towards one of the greatest discoveries of the century, the results of which will be of invaluable benefit to mankind.”[8] And so they were. Though Lazear’s one-year-old son and newborn daughter never knew their father, they grew up in a world liberated — almost in its entirety — from the disease that killed him.

Sources