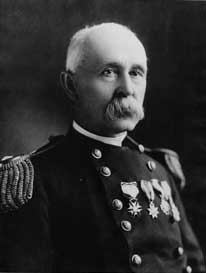

Army Surgeon-General George Sternberg on Typhoid Fever and the Spanish-American War

A map of Cuba. From the title pages of An Illustrated History of Our War with Spain (1898) by Henry B. Russell

At the onset of the Spanish-American War in 1898, America’s military planners were less concerned with typhoid fever than with yellow fever, Spain’s military forces, and most of the other major challenges they anticipated. Much of the typhoid-related optimism originated with Brigadier-General George M. Sternberg, a leading bacteriologist and Surgeon-General of the United States Army. On April 25, the day the Congress of the United States declared war on Spain, he issued a series of etiological explanations and sanitary recommendations in Surgeon-General’s Circular No. 1.

George Miller Sternberg

Waterborne Typhoid

The Circular noted that typhoid fever was contagious and identified specific means for its transmission. In accordance with the findings of pioneering typhoid-investigator William Budd, Sternberg emphasized the danger of polluted water and prescribed boiled or filtered supplies for troops who lacked a source pronounced pure by a medical officer. He urged their commanders, moreover, to avoid waterborne typhoid by selecting only those campsites possessing effective drainage. In subsequent guidelines Sternberg tutored medical officers on the supervision of water filtering, in devices the War Department issued on his recommendation, and water testing.

Latrine Use and Flies as Typhoid Vectors

Although Budd, author of Typhoid Fever: Its Nature, Mode of Spreading, and Prevention, had overlooked flies as typhoid vectors, Sternberg’s Circular noted that countering their propensity to “swarm around fecal matter” was as powerful a justification for “strict” sanitary measures as avoiding polluted water. Those measures included officers’ obligation to favor previously unoccupied sites when locating camps. The Circular recommended that their subordinates dig latrines, also known as “sinks” or “privy-pits,” as the first step in camp-establishment and dig replacement pits when the contents of the originals came within two feet of the ground’s surface. Sternberg added that soldiers who declined to use latrines “should be punished.”

Disinfection of Latrines

No less an optimist than Surgeon-General George Sternberg, the manufacturer of this patriotic cover assumed that sectional amity and reconciliation would represent the principal, domestic by-products of the Spanish-American War mobilization. The cover’s actual user, however, enclosed a letter detailing the stateside ravages of typhoid fever. Courtesy of Noel G. Harrison

Disinfection lay at the heart of Sternberg’s waste-disposal technology: he stipulated that soldiers should cover the contents of latrines thrice-daily with earth, quicklime, or ashes. Army medical personnel should treat the excreta of all fever patients immediately with a solution of carbolic acid, chloride of lime, or with milk of lime made from quicklime.

Typhoid Mortality Rates

Sternberg’s faith in “progress” notwithstanding, in the Spanish-American War’s fourth month the United States Army’s typhoid mortality rate surpassed that of its fourth-month Civil War counterpart. To make matters still more vexing for Sternberg, typhoid statistics were especially bad in the Army’s stateside training camps, situated far from what were understood to be the sites of combat operations.