New Attempts at Prevention after Typhoid Devastates Army Training Camps

A 2nd Corps regiment in 1898, in the midst of one of the several camp-abandonments necessitated by typhoid fever. Courtesy of Noel G. Harrison

During the Spanish-American War soldier carriers of typhoid bacilli emerged abundantly and powerfully equipped, encountered only divided and uninformed opposition, and ‘recruited’ reinforcements at an exponential rate. By disabling thousands of fellow soldiers in the process, carriers prompted the War Department to order the abandonment of most of the major training camps it opened at the outset of war.

Relocation of Army Training Camps

The United States Army consequently undertook a series of mass-retreats and attempted evasions. Two divisions of the 1st Army Corps moved from Chickamauga, Georgia to Lexington, Kentucky and Knoxville, Tennessee. The 2nd Army Corps moved first from Falls Church, Virginia to Dunn Loring, Virginia and Thoroughfare, Virginia, and then to Middletown, Pennsylvania. The 3rd Army Corps moved from Chickamauga, Georgia to Anniston, Alabama. In Florida the 4th Army Corps journeyed from Tampa to Fernandina.

In evaluating this dramatic response the Typhoid Board determined that the carriers proved as adept at transporting bacilli, in and on their bodies and on their possessions, between states as between neighboring regiments. The inhabitants of some camps found peace only after their assailants finished infecting all susceptible men, numbering in the Board’s estimation as much as one-third of a “thoroughly saturated” regiment’s strength. When attacked by pathogen-carriers, retreat alone was futile.

Strict Typhoid Prevention Measures: Latrine Policy, Disinfection, and Camp Relocation

Company B, 7th Regiment Illinois Volunteers, after a medical examination. From Medico-Surgical Aspects of the Spanish American War (1900) by Nicholas Seen, p.21

The Board concluded that only one of the five army corps stricken with epidemic typhoid succeeded in suppressing the disease actively. In the wake of two fruitless relocations and months of casualties, commanders of the 2nd Corps finally managed to impose an effective latrine-policy, described as “tyrannical” by one of the Board’s interviewees. Next, the Corps’ officers ordered disinfection of the clothing, blankets, and tents of the entire organization, numbering some 15,000 soldiers. Immediately thereafter they oversaw a third relocation, from Pennsylvania to Georgia and South Carolina.

Armed with the Board’s preliminary report, Surgeon-General George Sternberg concluded in 1899 that undisciplined and discipline-resistant soldiers carried typhoid from civilian society, where the disease was “endemic,” and transformed the stateside training camps into battlefields. The men stationed there, he wrote, suffered “all the privations and exposures of troops in actual conflict with an enemy … excepting only the danger from gunshot injuries.” Elaborating on this interpretation, the Board’s final report traced the course of the civil war from the mobilization stage through the pathogen-carriers’ lopsided victories first at the tactical level and then at the strategic level. In that final report Victor Vaughan declared that, “the commanding officer who needlessly and ignorantly sacrifices his men to disease is as unworthy of his position as one who makes a like sacrifice in the face of the enemy.”

The 2nd Army Corps’ three-part strategy of draconian defecation-management, mass-disinfection, and flight received the Typhoid Board’s imprimatur as the principal, recommended method for suppressing existing epidemics. In future wars, however, commanders who initiated such a battle would thereby hinder their ability to fight a conventional enemy simultaneously. Not surprisingly, then, Surgeon-General Sternberg was as eager to employ the Board’s members in a preventative capacity as he was to employ them in a suppressive capacity.

Typhoid Board Promotes New Equipment to Manage Urine and Feces and to Sterilize Water

Plans for the Typhoid Board’s Reed Trough and the building that housed it. From Report of the Surgeon-General of the Army (1899), p.212

Amid mounting evidence of soldier recalcitrance, the Typhoid Board condemned the use of surface tub-latrines and sub-surface privy-pits. Sternberg reached similar conclusions around the time the three surgeons completed their camp tour and returned to Washington, D.C. In October 1898, he proposed a new policy to the War Department: when wartime exigencies delayed or precluded the installation of sewers, delegate excrement-management largely to portable or easily assembled technical systems, rather than to people.

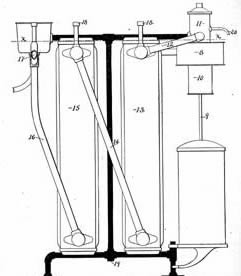

Two months later the Typhoid Board submitted plans for a structure, eventually dubbed the “Reed Trough,” that featured a long urinal; a multi-seat latrine; and a fly-excluding, enclosed metal-trough where disinfecting solutions treated all waste. The Board also drafted specifications for a six-wheeled, pump-and-tank wagon—the “Odorless Excavator”—that allowed its operators little opportunity for spillage while emptying the trough.

The Odorless Excavator, designed by the Typhoid Board to empty the Reed Trough. From Report of the Surgeon-General of the Army (1899), p.211

The Board’s ambivalence towards waterborne transmission of typhoid balanced its members’ certainty about the roles of contaminated people and flies. Although the three surgeons determined that “infected water was not an important factor,” they qualified this conclusion by reporting that some water supplies became “specifically infected” and, at Chickamauga at least, water was a prominent means of transmission if not its “chief” means. Reed devoted no less than six pages of his “Etiology” essay to prose illustrations, drawn partly from Shakespeare’s and Vaughan’s pre-war experiences, of the waterborne pathogen’s resilience and insidiousness. Sternberg agreed that water had proven itself a menace “frequently” before 1898 and directed the Typhoid Board to “consider and report upon the best method of sterilizing water for troops in the field.”

The Forbes-Waterhouse water sterilizer, as modified to meet the Typhoid Board’s specifications. From Report of the Surgeon-General of the Army (1899), p.221

The Board solicited proposals from six manufacturers, tested initial designs, suggested modifications, and then tested the revised designs. In late 1899, at about the time the War Department authorized the Reed Trough and the Odorless Excavator for field trials, the Board’s members recommended one of the six devices—the Forbes-Waterhouse Sterilizer, which likewise received the Department’s approval.

The Surgeon-General and the Typhoid Board’s members declined to extend their experimental approach to vaccination, or at least consideration of it at the published level they granted sterilizers and latrines. In December 1896, Reed had attended a meeting chaired by Dr. William S. Thayer of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Another attendee, Dr. Simon Flexner, suggested testing a promising new anti-typhoid vaccine “in barracks and army corps, where, as is well known, large and destructive epidemics sometimes occur.” Sternberg, however, viewed such prophylaxis as no substitute for sanitation; his reports and those of the Typhoid Board were silent on the subject of anti-typhoid vaccination for humans.