Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (1697-1770)

Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles of the Human Body. London: Printed by H. Woodfall, for John and Paul Knapton, 1749. 1777 edition available through Eighteenth Century Collections Online (UVa access only)

- Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles…. This 1749 English edition of the 1747 Latin text was published by John and Paul Knapton in London without Albinus’s permission. Concerned about plagiarism, Albinus issued a warning in another book he published four years later.

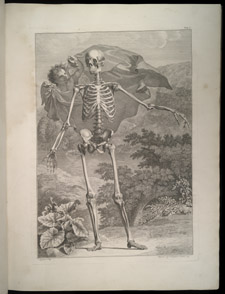

- Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles…. This first table “contains chiefly a front view or figure of the Human Sceleton; whereunto are added some of the Ligaments and Cartilages.”

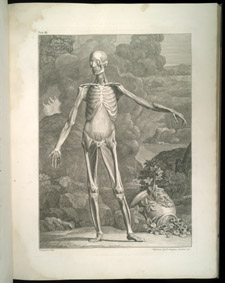

- Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles…. The third anatomical table of the human muscles shows the body with the outer muscles removed.

- Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles…. Additional muscles have been removed in this image of the fourth anatomical table of the human muscles. The rhinoceros grazing in the background adds an exotic note.

A native of Frankfurt, Bernhard Siegfried Albinus became a professor of anatomy at the University of Leiden at the age of 24. His books include some of the most beautiful and precise drawings of the human body ever published. It took Albinus and artist-engraver Jan Wandelaar over eight years to complete the 40 plates of this remarkable anatomical atlas with its aesthetic style, scientific accuracy, and fanciful backgrounds.

The foundation for Albinus’s illustrations is the human skeleton. Many anatomical drawings begin with the outside of the human body and then work their way deeper, but Albinus carefully removed all the muscles and ligaments so that the illustrations begin with the skeleton. He preserved the soft tissue and then added it to the skeleton to make his “muscle-man.”

In the “Account of the Work” at the beginning of his book Albinus gives a detailed explanation of the methods he used to prepare his skeleton and muscle-man. For support he used a tripod as well as numerous cords passed through the spine, arms, and legs that were then attached to his walls and ceiling. After making minor adjustments with pieces of paper and wood, he explains how he checked the accuracy of the skeleton’s pose, “I next looked out for a thin man, of the same size with my skeleton, and making him stand naked in the same position, I compared the skeleton with him.” Albinus endeavored to set a new standard in anatomical illustration by developing a technique of viewing the specimen through nets with grids that made the perspective and proportion of the human body more accurate. Toward the end of his account, Albinus warns, “he will find it no easy task neither [sic], who engages in an affair of the same kind.”

In addition to the plates of skeletons and muscle-men, each placed in a lush, natural scene that helps to animate the figures and “emphasize the harmonious and natural beauty of the body,” there are over 300 superb drawings of separate muscles and muscle groups.

next author: William Smellie (1697-1763).