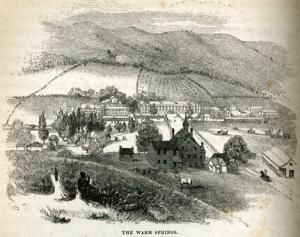

Warm Springs

Bath County, Virginia

All who have described this noble fountain, write with enthusiasm; nor is it indeed to be wondered at, for the world may well be challenged for its equal. Its temperature, buoyancy, refractive power, transparency – all invest it with indescribable luxury to the feelings and to the sight. William Burke

William Burke on the Warm Springs.

The Warm Springs, later called the Jefferson Pools, are only five miles from Hot Springs and located in the aptly named Bath County of Virginia. Legend has it that a young Indian traveling more than 200 years before the printing of Burke’s book happened on the spring when he was weary and dispirited. Coming upon the narrow valley filled with water, he first tasted, and then plunged into, the warm waters. Refreshed and invigorated, he continued his trek the next day successfully reaching his destination. Whether this tale is true is debatable, but it is accepted that the waters were used both for bathing and therapy in the later part of the eighteenth century. In the western area of Virginia, Warm Springs and Sweet Springs were the first two springs to be visited by great multitudes.

The brick hotel associated with the springs had accommodations for about 100 people and offered good fare. Burke found the establishment clean and neat with “servants among the best in Virginia.” The octagonal bath house was forty feet from angle to opposite angle and five to six feet deep with a gravelly bottom. The day was divided into two hour periods with men and women alternately occupying the pool. A white flag flew when women were taking the bath. The 96 degree water was plentiful enough that if the bath was drained, it could be replenished in 15 minutes to an hour. Nearby springs, one also warm and another cold, were used for drinking. Children and the “more aged and infirm” used another smaller bath.

Burke’s Recommendations for Using the Waters at Warm Springs.

Burke included a lengthy article about Warm Springs published in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1838. The article indicated that the analysis of the water by Professor William Rogers from the University of Virginia showed that the gas bubbling up was mainly nitrogen with small amounts of sulphuretted hydrogen (hydrogen sulfide) and carbonic acid. These same gases were found within the water as well as salts including magnesium sulfate or Epsom Salts. These salts and gases worked as gentle diuretics and laxatives. The Messenger paper indicated that the waters were not a panacea in all cases and that the baths were best avoided by those with a high fever or a full stomach, but had been effective in dyspepsia of long standing, chronic rheumatism, and paralytic afflictions especially if the patient bathed in the water and drank the water for a period of time.

Calling the Warm Spring bath “one of the greatest subjects of curiosity in Western Virginia, Burke also cautioned about the “sunny side of the picture” and wrote, “… it is necessary that the traveller should know there is danger in the indulgence. Experience, fatal in some cases, has taught this fact.” He proceeded to explain that the nitrogen in the lovely bubbles rising to the surface of the spring had the potential to cause “great distress in the pulmonary apparatus.” Burke was careful to write that most people could enjoy and benefit from the bath and included the Messenger paper so that readers could judge for themselves the various merits and dangers.

Thomas Jefferson and Warm Springs.

Thomas Jefferson was at Warm Springs in August 1817 and saw the need for a resident physician to attend those seeking healing at the various springs. Anticipating men like Dr. Burke at Red Sulphur Springs, Dr. Moorman at White Sulphur Springs, and Dr. Goode at Hot Springs, he wrote, “it would be money well bestowed could the public employ a well educated and experienced physician to attend at each of the medicinal springs, to observe, record, and publish the cases which recieve benefit, those recieving none, and those rendered worse by the use of their respective waters.” {Jefferson}

“… tried once to-day the delicious bath and shall do it twice a day hereafter … but little gay company here at this time, and I rather expect to pass a dull time.”

With the hope of helping his rheumatism, Thomas Jefferson revisited Warm Springs in 1818. His initial assessment of the effect of the spring water was positive but his visit led to near-disastrous results. On August 4, he wrote his daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, “Every body tells me the time I allot to the Springs is too short. That 2. or 3. weeks bathing will be essential. I shall know better when I get there.” {Betts and Bear, 423} Three days later Jefferson wrote Martha that he had journeyed by horseback to the springs and had “tried once to-day the delicious bath and shall do it twice a day hereafter.” He described the table as well kept and the other guests numbering about 45, “but little gay company here at this time, and I rather expect to pass a dull time.” {Betts and Bear, 424}

“… so dull a place, and distressing an ennui I never before knew. … the spring with the Hot and Warm are those of the first merit. The sweet springs retain esteem, but in limited cases.”

One week later on August 14, 1818, Jefferson wrote his daughter that he continued to bathe for 15 minutes three times a day and presumed that the seeds of his rheumatism were eradicated. He decided to yield to the general advice of a three week course. He wanted “to prevent the necessity of ever coming here a 2d time” because, “so dull a place, and distressing an ennui I never before knew.” While he found little to enliven his time, he did write, “the spring with the Hot and Warm are those of the first merit. The sweet springs retain esteem, but in limited cases.” {Betts and Bear, 425}

“A large swelling on my seat, increasing for several days past in size and hardness disables me from sitting but on the corner of a chair.”

The tone of his letter on August 21st changed substantially. He wrote his daughter, “I do not know what may be the effect of this course of bathing on my constitution; but I am under great threats that it will work it’s effect thro’ a system of boils. A large swelling on my seat, increasing for several days past in size and hardness disables me from sitting but on the corner of a chair. Another swelling begins to manifest itself to-day on the other seat.” {Betts and Bear, 426}

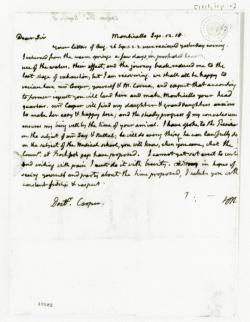

Jefferson’s letter of September 12, 1818 to Dr. Thomas Cooper stated that he had returned from the Warm Springs several days earlier though not in the condition he had hoped but instead “in prostrated health, from the use of the waters. Their effect, and the journey back reduced me to the last stage of exhaustion; but I am recovering.” He explained his brevity in writing as a result of not being able to sit erect due to pain.

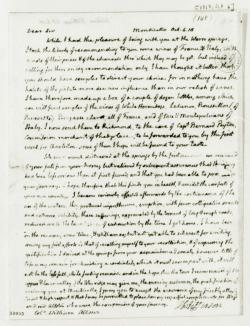

On October 6, 1818, Jefferson wrote to Colonel William Alston who must have provided some “gay company” to Jefferson during his visit to the springs as he was sending Alston wine and hoping for him to visit Monticello. He tells the colonel, “I became seriously affected afterwards by the continuance of the use of the waters. They produced imposthume [abscess], eruption, with fever, colliquative [profuse] sweats and extreme debility. These sufferings, aggravated by the torment of long & rough roads, reduced me to the lowest stage of exhaustion by the time I got home. I have been on the recovery some time, & still am so; but not yet able to sit erect for writing.”

On December 27, 1818, Jefferson wrote John Jackson that he appreciated the kind interest Jackson had concerning Jefferson’s health and claimed, “my trial of the Warm springs was certainly ill advised. for I went to them in perfect health, and ought to have reflected that remedies of their potency must have effect some way or other. if they find disease they remove it; if none, they make it. altho’ I was reduced very low, I may be said to have been rather on the road to danger, than in actual danger.”

Thomas Jefferson was not the only member of his family to visit the springs in western Virginia. On July 31st, 1795 Jefferson wrote his daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, “We have no letter from you since your arrival at the Warm-springs, but are told you are gone on to the sweet springs.” {Betts and Bear, 134} Presumably Martha’s spring visits had happier results than her father’s later visit.

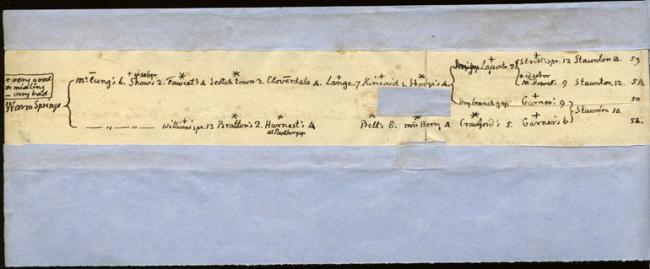

Thomas Jefferson’s table of mileages from Warm Springs, Virginia, to Staunton, Virginia, rates taverns and inns as very good, middling, or very bad. Several are ranked very good with the caveat “if sober.” {4}

Documents from the Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia:

- Diary by John Baylor, 1805: Baylor’s diary includes visits to various springs and notations of mileage, expenses, and lodging.

- Letter from John Baylor, 1805: Baylor describes his physical condition and his visit to the “Sulphur Springs” the day before. Probably referring to White Sulphur Springs, he writes that the springs’ buildings are constructed of logs and the offensive smell of the water is like “a dirty Barrel of a gun.”

- Diary of Alexander Dick, 1806: Dick mentions log huts; the smell of the copious spring; 50 to 60 people with attendant servants, horses, and carriages; one man who slept in the springs at night; and a near drowning.

- Letter from Edmund Randolph to Doctor Joshua E. R. Birch, October 10, 1810: This former governor of Virginia seeks advice for help with his paralysis which his trip to the Warm Springs did not alleviate.

- Letter from Till [Matilda Palmer]? 1833: Till writes Thomas Jefferson’s granddaughter that she was initially alarmed at Warm Springs’ strong sulphur smell, smoke, and rumbling noise, but became accustomed to it and enjoyed the bathing. The excursion did not improve her health which she fears is quite bad.

- Letter from Wm. W. Harvie, 1853: As guardian of the children of the recently deceased Dr. Brockenbrough, Harvie wants to buy the Warm Springs stock not already owned by the Brockenbrough estate.

- Diary of Philip St. George Cocke, 1853: Cocke mentions people he has met at Warm Springs in a diary that also discusses the early history of the Warm Springs Company.

- Letter from the Medical Director of the Army of West Virginia, 1861: Dr. Hunter is instructed to inspect and inventory hospital property at the Healing, Hot and Warm Springs.

- Letter from Robert E. Lee, 1866: Lee writes Professor Venable that he is taking his wife to the Rockbridge Baths and possibly to Warm Springs.

- Commissioners’ sale of the Warm Springs, 1871: This broadside advertises the Warm Springs as the “Paradise of watering places.”

- Charter of the Warm Springs Valley Company, [1890]: The Charter states the purposes of the Company is to include acquiring, improving, and operating the Warm, Hot, and Healing Springs.

Additional Information:

- National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: This form for the Warm Springs is dated April 23, 1969. It includes the history and significance of the springs, a description of the two bath houses, one map, and a bibliography.

- National Register of Historic Places, Warm Springs bath houses: The National Register has a brief summary of places in Bath County, Virginia.

- National Register of Historic Places bath house photo: View a photo of the men’s bath house.

- “Springs Time” by Lisa Provence: This Washington Post article describes the delights of the pools at Warm Springs.

- Jefferson Pools Warm Springs Bath County Virginia: View interior and exterior photos of the baths.

- Jefferson Pools: The current owner’s official Web site gives a history of the Jefferson pools (Warm Springs).

- Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia: In Jefferson’s section titled “Productions mineral, vegetable and animal,” he includes information about medicinal springs, one of which is Warm Springs.

Image Credits:

- {1} Merritt T. Cooke Memorial Virginia Print Collection, 1857-1907, Accession #9408, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

- {2} David HunterStrother, Virginia Illustrated: Containing a Visit to the Virginian Canaan, and the Adventures of Porte Crayon [pseud.] and His Cousins, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1857: p. 135.

- {3} Library of Congress American Memory: The Thomas Jefferson Papers. Search by date of the letter to see a higher resolution image.Accessed July 21, 2009.

- {4} Papers of Thomas Jefferson and other noted Revolutionary War figures, 1770-1822, Tracy W. McGregor Library, Accession #3620, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

Sources:

- Edwin Morris Betts and James Adam Bear, editors, The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson, Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1966.

- William Burke, The Mineral Springs of Western Virginia, New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1846.

- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Thomas Ritchie, Article for the Richmond Enquirer “Central College, A letter from a correspondent of the Editor of the Enquirer,” Warm Springs, August 1817. 68 Letters to and from Jefferson, 1805-1817. Accessed July 19, 2009.