Carrie Buck Revisited and Virginia’s Expression of Regret for Eugenics

[5.1] Carrie Buck shortly before her death. Image from The Lynchburg Story, a film distributed by Filmakers Library, produced in association with Discovery Networks/USA, producer, Bruce Eadie, director, Stephen Trombley, 1993.

Carrie Buck after Her Involuntary Sterilization

“They done me wrong.

They done us all wrong.”

The legal test case resulting in Carrie Buck‘s involuntary sterilization was premised on the acceptance of a politically popular social policy that mistakenly labeled her as feebleminded. Her defense attorney worked with the attorney for the Virginia Colony to assure that Virginia’s sterilization law would be upheld in Court.

[5.2] Carrie Buck with her first husband, William Eagle. Both images with husbands from The Lynchburg Story.

[5.2] Carrie Buck with her second husband, Charlie Detamore, whom she married nearly 25 years after the death of her first.

Carrie Buck was paroled from the Virginia Colony shortly after her sterilization was performed. She married twice, but expressed later in life her sorrow that she had been unable to have additional children. She spent most of her adult life helping others. Her competence was obvious in the quality of care she gave to those who depended on her. After Carrie died in a nursing home in 1983 she was buried near the grave of her only child in Charlottesville, Virginia.

ENLARGE

[5.3] Vivian’s first grade report card. Courtesy of Paul A. Lombardo.

Bearing an illegitimate child provided the basis for allegations of promiscuity against Carrie Buck, when, in fact, her pregnancy resulted from a rape, allegedly by the nephew of her foster parents. Carrie’s daughter, Vivian, was raised by her foster parents until she died at the age of eight from an intestinal disease.

Records from Venable Elementary School in Charlottesville demonstrate that Vivian was not “feebleminded.” Her first grade report card showed that Vivian was a solid “B” student, consistently received an “A” in deportment, and had been on the honor roll.

Epilogue: 75 Years after Buck v. Bell, Virginia Expresses Regret for Its Role in Eugenics

Although the eugenics movement was eventually discredited as arising from political and social prejudice rather than scientific fact, few of the the legislative bodies that passed compulsory sterilization laws have ever compensated or apologized to the more than 60,000 victims. The United States Supreme Court affirmed Virginia’s sterilization law on May 2, 1927, in the Buck v. Bell decision, and the constitutionality of that ruling has never been challenged nor has the ruling ever been overturned. Virginia repealed the 1924 sterilization law in 1974, while compulsory sterilization of those with “hereditary forms of mental illness that are recurrent” was a part of the Virginia Code until 1979.

In the late 1990s, pressure was exerted on the Virginia State Assembly to acknowledge the injustice of the sterilization law after historians and reporters drew clear links between the Virginia law and the enthusiasm shown for eugenics by Nazi Germany.

Efforts to obtain an apology from the General Assembly were abandoned quickly as sponsors feared some lawmakers would resist. Even the proposed expression of regret drew opposition. One Senator referred to a “trend in this country to recreate history. Now we go back and stir the pot on history, and take the most unfortunate chapters in our history and try to relive them for no real reason.”

Stopping short of a full apology in 2001, the Virginia General Assembly with House Joint Resolution No. 607 expressed “profound regret” for the “incalculable human damage done in the name of eugenics.”

In January of 2002, House Joint Resolution No. 299 honoring the memory of Carrie Buck was passed by the General Assembly of the state that forcibly sterilized her 75 years previously. This resolution states that “legal and historical scholarship analyzing the Buck decision has condemned it as an embodiment of bigotry against the disabled and an example of using faulty science in support of public policy.”

ENLARGE

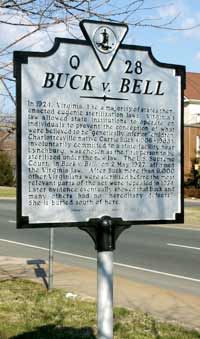

[5.4] Historical marker erected on May 2, 2002 Courtesy of Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

An historical marker was erected on May 2, 2002 in Charlottesville, Virginia where Carrie Buck was born. At this time, Virginia Governor Mark R. Warner offered the “Commonwealth’s sincere apology for Virginia’s participation in eugenics,” noting that “the eugenics movement was a shameful effort in which state government never should have been involved.”

Both events took place at the urging of Paul A. Lombardo, Ph.D., J.D., who was the Director of the Program in Law and Medicine, Center for Biomedical Ethics, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine at the time this website was published. He has studied and written about Carrie Buck’s case for more than 20 years.