Influence of Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Act

Leaders of the Eugenics Movement in Virginia

“… the greatest social revolution the world has yet known….” Photograph of H.E. Jordan and image of his publication, Eugenics: The Rearing of the Human Thoroughbred. Courtesy of Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

[4.1]

Although Virginia was not the first state to pass an involuntary sterilization law, efforts to obtain passage of such a law had been taking place for a number of years in the state and support for the eugenical movement had taken root in the preceding decades.

The University of Virginia was home to supporters of the science of eugenics. Dr. Harvey E. Jordan who became Dean of the Department of Medicine at the University in 1939 delivered an address in 1912 in which he stated:

It is not too much to say, I believe, that the idea of eugenics, based upon the science of eugenics, will work the greatest social revolution the world has yet known. Closely related to the concept of evolution, which has left its impress on every department of human thought, the idea of eugenics can hardly be compared with it in the pregnancy of its promise, the immensity of its scope, and in the serious import of its reception or neglect for the future trend of nations. It aims at the production and the exclusive prevalency of the highest type of physical, intellectual and moral man within the limits of human protoplasm.

[4.2] Photograph of Joseph S. DeJarnette. Courtesy of The Virginia Challenge (March 1, 1947), A publication of the Citizen’s Temperance Foundation.

Joseph S. DeJarnette, Superintendent of Western State Hospital, in Staunton, Virginia, was at the forefront of several previous efforts to clear legislative hurdles in Virginia. When these failed, DeJarnette vented his malice toward those members of the Virginia Assembly who prevented a sterilization law from going beyond the committee level by stating, “When they voted against it, I really felt they ought to have been sterilized as unfit.” DeJarnette testified at Carrie Buck‘s original court proceeding as one of Aubrey Strode‘s expert witnesses.

Years later he wrote Strode a letter which was written on Western State Hospital letterhead stationery and is now in the Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia:

July 24, 1939

Judge Aubrey E. Strode

Lynchburg, VirginiaDear Judge Strode:

I want to thank you for the splendid address you made at my fiftieth anniversary

celebration. It was kind of you and Mrs. Strode to come.I can hark back many years when first I knew you. I have heard you speak in the Senate and had your cooperation in the great sterilization law of the United States. We can call it the United States law because it was the first law of the kind ever approved by the United States Court of Appeals.

If you had never done anything else you would have done more for your State than anyone [sic] man in it. We have sterilized in Virginia 3300 and we estimate that in 100 years we will have saved the State of Virginia over four hundred million dollars. At the same time we are raising the mentality of our people and saving suffering, murder, accidents, crime — and the greatest crime of all is allowing the feeble minded people to raise children in a feeble-mind environment.

I wish to thank you again for attending and participating in my anniversary celebration, and I hope you will allow me to call you my friend.

Sincerely yours,

J.S. DeJarnette, M.D.

ENLARGE

[4.3]DeJarnette wrote a chilling poem entitled “Mendel’s Law,” of which he was very proud. He presented it publicly on several occasions. Courtesy of Paul A. Lombardo.

DeJarnette also wrote a poem subtitled, “A Plea for a Better Race of Man,” and starts with these two stanzas:

Oh, why are you men so foolish -

You breeders who breed our men

Let the fools, the weaklings and crazy

Keep breeding and breeding again?

The criminal, deformed, and the misfit,

dependent, diseased, and the rest -

As we breed the human family

The worst is as good as the best.

Go to the house of some farmer,

Look through his barns and sheds,

Look at his horses and cattle,

Even his hogs are thorough breds,

Then look at his stamp on his children,

Low browed with the monkey jaw,

Ape handed, and silly, and foolish -

Bred true to Mendel’s law.

Eugenics in the United States and the Influence of Buck v. Bell

ENLARGE

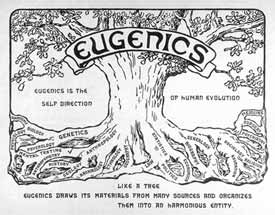

[4.4] Eugenics Tree Logo. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society. From 1907 onward, at least 60,000 Americans were sterilized against their will. California and Virginia led the nation in the number of sterilizations performed per state. The legal basis for these forced sterilizations was the so-called science of eugenics.

Most involuntary sterilizations occurred in the 1930s and 1940s, but some states, such as Virginia, continued the practice until the law was repealed in the 1970s. Most of the victims were poor and uneducated, and none received compensation. The alignment of eugenics and race purification is commonly associated with Nazi Germany, but the fervor of the eugenics movement in the United States is less widely acknowledged despite the vanguard role played by American scientists. These advocates pushed for the perfection of the human “gene pool” by influencing the reproductive process. A table included in the Proceedings of the First National Conference on Race Betterment, 1914, stated: “Under the present estimate it would be necessary to sterilize during this period approximately 15,000,000 persons–beginning with 92,400 per year in 1915 and increasing to 415,000 per year by 1980.”

The impact of the Buck v. Bell decision was felt nationwide. After the 1927 decision affirmed Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Law, there was a swift rise in the number of involuntary sterilizations in the United States. By the early 1930s, thirty American states had adopted eugenics laws. American eugenicists also pushed for anti-immigration measures and stricter laws to prevent racially mixed marriages. When signing the 1924 Immigration Restriction Act, President Calvin Coolidge stated: “America must remain American.”

ENLARGE

[4.5] Efficiency rate chart from the Proceedings of the First National Conference on Race Betterment, 1914.

For a time, the doctrine of eugenics exerted considerable influence on American society. Based largely on political and social prejudices, the pseudo-science was taught at schools and universities. Leading institutions, such as Harvard, Cornell, Columbia, and the University of Virginia offered courses in eugenics.

During the 1940s, however, eugenical theory came under increasing criticism because of its racial prejudices and its lack of scientific foundation. Many American sterilization laws were abandoned during the 1950s. Virginia’s sterilization law was repealed by the General Assembly in 1974.

Virginia’s International Influence on Eugenics: Nazi Germany and Beyond

ENLARGE TO VIEW THIS AND ADDITIONAL LETTERS

[4.6] Invitation sent to Harry H. Laughlin by the University of Heidelberg to attend ceremonies commemorating its 550th anniversary, during which he would be awarded an honorary doctorate for his “services on behalf of racial hygiene.” Courtesy of Special Collections, Pickler Memorial Library, Truman State University.

Using language from Laughlin’s Model Law, Germany’s Nazi government adopted the Law for Protection Against Genetically Defective Offspring in 1933 that provided the legal basis for sterilizations in Germany. In its first full year of operation, the Nazi program dramatically eclipsed activities in the United States, sterilizing about 80,000 persons without their consent. The much grander scope was achieved because the Nazi law applied to the entire population rather than just institutionalized persons. A system of hereditary health courts was designed exclusively to hear and process petitions for sterilization. These courts allowed a broad range of citizens to propose that an individual should be sterilized. Superintendent of the Virginia Colony, Dr. J.H. Bell, theorized about global acceptance of sterilization writing: The fact that a great state like the German Republic, which for many centuries has helped furnish the best that science has bred, has in its wisdom seen fit to enact a national eugenic legislative act providing for the sterilization of hereditarily defective persons seems to point the way for an eventual worldwide adoption of this idea.

ENLARGE

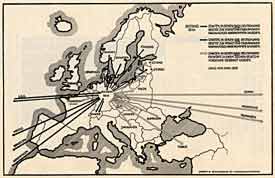

[4.7] Map of countries in the process of adopting sterilization laws in 1936. Courtesy of Paul A. Lombardo.

Often overlooked in discussions of Nazi eugenic practices are the sterilization programs implemented during the 1930s in other European countries as well as in other nations around the globe. In smaller nations such as Sweden, which had an active eugenic sterilization program until the 1960s, the impact of the programs was proportionally larger than in the United States.

The rate of sterilizations in the United States did not seem to satisfy Dr. Joseph S. DeJarnette, director of Western State Hospital in Virginia, when he made this comparison in 1938: Germany in six years has sterilized about 80,000 of her unfit while the United States with approximately twice the population has only sterilized about 27,869 to January 1, 1938 in the past 20 years … The fact that there are 12,000,000 defectives in the US should arouse our best endeavors to push this procedure to the maximum.