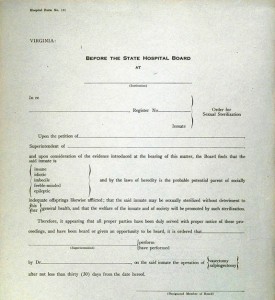

Buck v. Bell: The Test Case for Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Act

[3.1] Photograph of Carrie and Emma Buck at the Lynchburg Colony. Courtesy of M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections, State University of New York at Albany.

Carrie Buck’s Story

As soon as Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Act was passed by the General Assembly in 1924, Virginia Colony officials selected 17 year old Carrie Buck of Charlottesville to test the law’s legality. Carrie Buck’s foster parents had committed her to the Virginia Colony shortly after she gave birth to an illegitimate child. The family’s embarrassment may have been compounded by the fact that Carrie’s pregnancy was the result of being raped by a relative of her foster parents. This point was never raised in the subsequent court proceedings. Carrie’s mother, Emma Buck, had previously been committed to the asylum.

ENLARGE

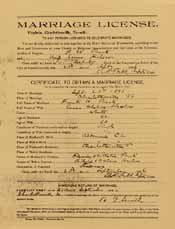

[3.2] Frank Buck and Emma Harlow’s marriage license, 1896. Courtesy of Paul A. Lombardo.

Officials at the Virginia Colony asserted that Carrie and her mother shared the hereditary traits of feeblemindedness and sexual promiscuity. With Emma and Carrie already institutionalized, if it could be demonstrated that Carrie’s daughter, Vivian, was likely to grow up to be an “imbecile” like her mother and grandmother, the case for inheritance of such a quality would be assured. After pushing for passage of a sterilization law in Virginia that would legally sanction procedures already taking place privately at the Virginia Colony, Superintendent Albert Priddy wanted a challenge to the law that would definitively strengthen its validity. The marriage license shows that Carrie’s mother, Emma, was married to Carrie’s father, Frank, ten years before Carrie’s birth although it was claimed that Carrie was an illegitimate child.

ENLARGE

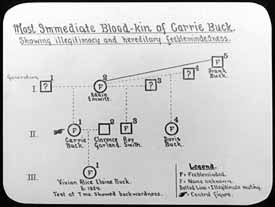

[3.3] Carrie Buck’s pedigree: Most Immediate Blood-kin. Courtesy of Special Collections, Pickler Memorial Library, Truman State University.

This chilling rendering of Carrie Buck’s pedigree chart was found in Harry H. Laughlin‘s notes. It is done in the standard Eugenics Record Office format used to demonstrate the hereditary passage of undesirable traits.

Compulsory Sterilization at the Virginia Colony for the Epileptic and Feebleminded

[3.4] A collage of images of the boys and girls, young men and young women who resided at the Virginia Colony. Collage from “The Lynchburg Story,” a film distributed by Filmakers Library, produced in association with Discovery Networks/USA, producer, Bruce Eadie, director, Stephen Trombley, 1993.

When the Virginia Colony for the Epileptic and Feebleminded, located in Lynchburg, Virginia, opened its doors in 1910, it was the largest asylum in the United States. It was originally intended to be a home for epileptics, the mentally retarded, and the severely disabled. In 1912, Virginia Colony Superintendent Albert Priddy, lobbied the Virginia General Assembly for funds to expand the Colony to provide residential space for those deemed “feebleminded.”

Such a determination was subjective at best, but as asserted by Priddy, was considered an hereditary quality meriting segregation from the rest of society in order to prevent proliferation. The authorizing legislation specifically directed the admission of “women of child-bearing age, from twelve to forty-five years of age” as the first patients.

Soon the Virginia Colony, also known as the Lynchburg Colony and The Colony, became a collecting place for poor, uneducated, white Virginians who were regarded as “unfit” by the state. Once in the Colony, the intelligence of the inmates was assessed. Some attended school at the Colony while others received basic skill training. Some received neither. As the population of the Colony grew, Priddy began to focus on a way to prevent patient reproduction that was more cost effective than long-term segregation from the general population. In 1914, he contributed to a report to the General Assembly entitled Mental Defectives in Virginia, proposing large-scale institutional sterilization for Virginia’s feebleminded.

Prior to passage of Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Act of 1924, sterilization procedures had been taking place at the Virginia Colony, and were justified as “for the relief of physical suffering.” After the law was passed by the General Assembly, immediate targets of sterilization were the allegedly feebleminded women who were committed to the Colony, but hired out in servile positions to work for “normal” families.

In the pseudo-science of the eugenics movement, Albert Priddy found a home for his own sense of moralism and a justification that it was his right and his duty to determine who should and should not be allowed to reproduce. Included in his list were “anti-social morons,” prostitutes, and “non-producing and shiftless persons, living on public and private charity.”

Eugenic Social Theory Becomes Compulsory Sterilization Law

[3.5] Albert Priddy. Courtesy of Special Collections, Library of Virginia.

[3.5] Aubrey Strode. Courtesy of Special Collections, Library of Virginia.

[3.5] Irving Whitehead. Courtesy of Special Collections, Library of Virginia.

The right of the state to perform the sterilization procedure was first challenged and heard in the Circuit Court of Amherst County. This test case was due in large part to the combined efforts of three men. Albert Priddy was superintendent of the Virginia Colony. Aubrey E. Strode was the man who drafted Virginia’s sterilization law. Irving P. Whitehead was the attorney whose weak defense of Carrie Buck almost assured that the law would stand. Whitehead had served on the Board of Directors of the Virginia Colony and Strode had previously acted as legal counsel to the Board. All three men knew one another politically, professionally, and personally for many years prior to the Buck litigation.

Aubrey E. Strode presented more than a dozen witnesses including four “expert” witnesses in the field of eugenics to prove Carrie’s “feeblemindedness.” Carrie’s court-appointed attorney, Irving P. Whitehead, called no witnesses to challenge the charges made about Carrie’s mental health or to question the science behind the eugenical theory espoused by the so-called expert witnesses despite evidence and opportunities to do so. The Amherst County Circuit Court affirmed the validity of the sterilization law as expected, and the case was primed to go before the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals before proceeding to the Supreme Court of the United States.

[3.6] Mrs. Alice Dobbs, the foster mother of Carrie Buck’s daughter Vivian, holds Vivian while flashing a coin past the baby’s face, in a test to assess her intelligence. The infant, perhaps distracted by the camera, didn’t follow the coin with her eyes and thus was declared an imbecile. A.H. Estabrook, the person who initiated this test of the infant’s intelligence and the photographer, took this picture the day before the Buck v. Bell trial in Virginia. Courtesy of M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections, State University of New York at Albany.

Harry H. Laughlin did not appear at Carrie Buck’s initial trial, but instead sent a written deposition containing sworn testimony. Although he had never met any members of the Buck family, he confidently reasserted Priddy’s statements that the family were members of “the shiftless, ignorant, and worthless class of anti-social whites of the South.” He focused on Emma Buck’s syphilis as evidence of her moral degeneracy and stated that Carrie was an illegitimate baby. One of Carrie’s teachers was brought in to testify that she sent flirtatious notes to schoolboys, a fact which was used to support the idea that she had inherited sexual precociousness from her promiscuous mother. Carrie’s baby, Vivian, was examined by a nurse who stated that “there is a look about it that is not quite normal.” Arthur Estabrook, a trained field worker from the ERO, testified as an expert witness about assessments he made of Emma, Carrie, and Vivian, determining that at the age of six months, Vivian was “below the average,” and likely as well to be feebleminded.

Buck v. Bell: U.S. Supreme Court Upholds Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Law

[3.7] Photograph of J.H. Bell. Courtesy of Journal of Heredity, 1934.

[3.8] Photograph of the Halsey Jennings Building at the Lynchburg Colony, site of Carrie Buck’s sterilization. Courtesy of Paul A. Lombardo.

Albert Priddy died before appeals were heard in the case. Dr. John H. Bell became superintendent of the Virginia Colony and his name replaced Priddy’s as party to the suit in the appeals process.

In November of 1925, the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals affirmed the ruling of the Amherst County Circuit Court. A petition for certiorari was filed, briefs were submitted and on May 2, 1927, the United States Supreme Court upheld Virginia’s eugenical sterilization law by a vote of 8 to 1 [Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927)].

In his opinion, Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. relied on an earlier case, [Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1904)], which upheld a Massachusetts law requiring school children to be vaccinated against smallpox in support of the Court’s decision. The assertions of the expert witnesses at Carrie Buck’s original trial laid the groundwork for Chief Justice Holmes’ resounding statement, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

On October 19, 1927, Carrie Buck was the first person in Virginia sterilized under the new law.