French Caricature: Medicine in France

The beginning of the eighteenth century in France saw its health system little changed from the Middle Ages. But by the end of the century, war and upheaval had altered French medicine. Revolutionary leaders condemned medical institutions and organizations, as well as doctors, but instead of the expected eradication of these institutions and professions, the movement ultimately resulted in progressive public health policies and new medical schools that produced better-educated doctors.8

The medical regulations law of 1803 stipulated a two-tier model for education. Health officers received predominantly practical training, but doctors were required to attend four years at a state medical school and pass examinations in anatomy, physiology, pathology, nosology, material medica, chemistry, pharmacy, hygiene, forensic medicine, and clinical medicine.9

Hospital reform resulted in a milieu conducive for clinical research, autopsies, and statistical analysis. By 1830 the 30 hospitals in Paris could accommodate 20,000 patients.10

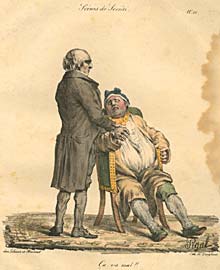

Ça va mal!! Edme Jean Pigal, (Scènes de Société. No. 16.), Lith. de Langlumé, chez Gihaut et Martinet.

This Edme Jean Pigal lithograph with the caption, “It’s bad!!” shows a doctor who exudes superiority and importance with his erect pose and intense gaze. He takes the pulse of his suffering patient who deferentially gazes up as he awaits the prognosis. The patient’s attire, chair, and substantial abdomen indicate he is in the ranks of the prosperous.

In the early nineteenth century, a French physician might see fewer than ten patients daily, sometimes only two or three. This low utilization of professional care was principally due to the high cost of health care compared to earnings. A visit by a health officer, who would have had less formal training than a doctor, might cost an agricultural worker a day’s wage, even without a charge for the practitioner’s travel. A doctor’s house call could be two or three times as high. In Paris, where doctor fees were considerably more than those charged by a rural health officer, an urban artisan could pay a week’s wages just for the doctor’s visit.11

Remedies cost extra, so it is not surprising that a doctor’s clientele consisted mainly of landowners and their servants, merchants, other professionals, and the more successful artisans.12

Medicine has proved to be a field rich in humor for centuries, and the French doctor’s rigorous training did not keep him from being an object of satire. In the middle of the nineteenth century Honoré Daumier created a number of caricatures whose captions, some quoted below, took pointed jabs at the medical profession. Doctors were ridiculed for excessive charges:

…Believe me, drink water, lots of water… rub the bones of your legs… and come to see me often… that won’t impoverish you… my consultations are free… Now, you owe me 20 francs for these two bottles…

ineffectual treatments such as bleeding:

…I’m going to apply thirty leeches to your epigastrium and if tomorrow I don’t find you improved, I’ll apply sixty…

and purging:

How the devil does it happen that all my patients succumb?… Yet I bleed them, I physic them, I drug them… I simply can’t understand!

impractical operations:

…you’ve seen this operation, that everyone said was impossible, performed with complete success…—But, Doctor, the patient’s dead…—What of it! She would have died anyway…

and caring more about the chance to treat an interesting illness than the well-being of the patient:

By Jove, I’m delighted! You have yellow fever… it will be the first time I’ve been lucky enough to treat this disease!13

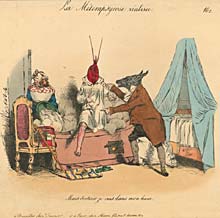

Mais docteur je cuis dans mon bain. (La Métempsycose réalisée. No. 2.), á Bruxelles chez Daemll[?], et á Paris, chez Méant, fils, rue St. Antoine, No. 9.

This print styled after Grandville, shows a patient not just turning as red as a lobster, but actually being transformed into a lobster, ready to be eaten by his persecutors. The central figure protests, “But Doctor, I cook in my bath.” The patient with his pinkish leg attempts to get out of the tub, but the wolf-headed physician has one hand firmly on his shoulder and the other sternly pointing to the water forcing the patient to stay in his bath. The dog-faced servant pours additional water into the tub that has at its base a small window showing a built-in compartment for fire to heat the water. Billowing clouds of steam illustrate the fire’s effectiveness. It appears that the therapy might just be worse than the ailment, not an uncommon occurrence given the state of medical treatment at the time.

En gouterai je? L. Noël, Lithog: de F. Noël, Publié par Giraldon – Bovinet et Compie, Mds d’estampes, Commissionnaires, rue Pavée St. André, No. 5.

The caption, “Will I like it?” is not required to understand this print. A seated man wearing a lounging robe and nightcap contemplates the unpleasant task before him. On his table rests a book, possibly one giving recipes for medical concoctions, and a labeled bottle with the cork removed. As he stirs the liquid in his cup, he peers out of the lithograph as if asking the viewer his question. His puckered-up face indicates that he already knows the answer.