English Caricature: Cost of Health Care, Pray Remember the Poor Debtors

Today one of the major social concerns in the United States is the rising cost of health care. People complain about the prices charged for a doctor’s appointment and for expensive prescription medicine. It was no different in nineteenth-century England. The cost of a doctor’s visit increased as the medical field became more professionalized. Many medical practitioners sought university degrees; over 8,000 university men became doctors between 1801 and 1850.10 Some of these highly trained physicians practiced at one of the 70 new specialty hospitals that were founded during this time in England.11 An extremely successful medical practice, especially one catering to the upper class, could make a physician wealthy.12

Although misunderstanding the root cause of disease, these highly educated physicians methodically identified, classified, and described various maladies. Some of the more noted English physicians were Thomas Hodgkin, Thomas Addison, and Richard Bright, all of whom described diseases that carry their names today. The emphasis on thoroughly understanding the outward manifestation of illness required practitioners to spend a lot of time with patients to classify their symptoms. The physicians painstakingly recorded their patient’s history in order to formulate a diagnosis. They then initiated therapeutics; often resulting in daily visits to the patient to further refine the treatment. Historian Roy Porter writes, “Thus – for those who could afford such cosseting – everyone’s treatment was bespoke, perfectly tailored to his condition.”13 The costs associated with daily visits and medicines made it difficult for the working class or the impoverished to afford medical care.14

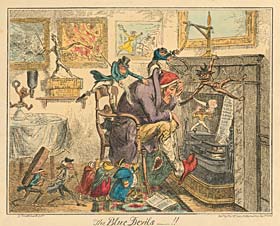

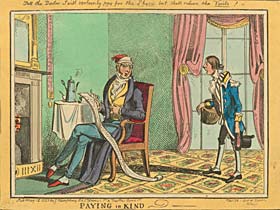

Like people today, nineteenth-century Britons lamented the exorbitant fees doctors billed. These caricatures deal with the high costs associated with health care. In the amusing cartoon, “Paying in Kind,” the doctor’s bill for medicine and house calls is so long that it trails on the ground. In “Faith” the caricature mocks the sheer quantity of medicine prescribed by the patient’s doctor. In the more thoughtful and provocative caricature, entitled “The Blue Devils,” the artist explores a melancholy world ushered in by debt, principally to the physician. Images of death stalk the beleaguered man, and the doctor serves as death’s deputy.

Paying in Kind. Anon, published by G. Humphrey, 27 St. James’s Street & 74 New Bond Street, W.H. Del & Sculpt, May 12, 1828.

In this caricature a well-dressed individual lounges in front of a fireplace. A messenger boy has just delivered a bill from the doctor. When the man unrolls the scroll, the lengthy bill rests on the floor. The man explains to the messenger, “Tell the Doctor I will certainly pay for the Physic but shall return the Visits!”

Nineteenth-century physicians commonly prescribed large quantities of drugs to treat a single illness, making it extremely difficult for the working class to afford medicine. In this caricature, a seemingly dimwitted middle-aged man stands in his robe, nightcap, pajamas, and slippers. He holds a large spoon filled with medicine poured from the bottle in his hand. Clearly this is not his first dose of medicine, as two empty bottles are strewn on the floor, nor will this be his last, as many more bottles await him on and under the table. The caption reads, “Bolus says that the last thirty doses have done me a World of good! I do’nt think so myself, but certainly the Doctor must know best.”

In this intricately detailed print, Cruikshank brings us into the life of a forlorn, solitary figure sitting hunched over a barren hearth. The drawing, entitled “The Blue Devils,” describes the depressed world of the protagonist. Three pictures hanging on the back wall symbolize the man’s life careening out of control. A devilish creature wielding a fiery paintbrush adds his own special touches to the artwork. The first painting depicts a boat sinking in a ferocious storm at sea. In the second, flames burst from a burning building. The final picture, this one not yet framed, shows a sketch of a man similarly dressed and posed as our protagonist. Behind him is an angry woman, presumably his wife, about to strike him over the head with what looks like a metal bed warmer.

All around the poor man there are imps and symbols encouraging him to choose death over life. A little devil on his shoulder holds a noose over his head. Another, hanging from the mantle, offers a knife. Yet another imp in the fireplace blows smoke out of his ears, while a monster with white fangs hungrily looks up from underneath the chair. Cruikshank even draws the andirons to resemble skeletons.

The protagonist falls into such depths of despair due to his inability to surmount the debts that have piled up around him. A sign hanging on the fireplace says, “PRAY REMEMBER the POOR DEBTORS.” A gentleman taps the debtor on the shoulder to give him a bill as a thief picks his pocket. Other debts appear to be doctor’s bills. In the fireplace, the bill has faint traces of the word “Dr.” written on it. On the table stacked with bills, an imp holds an empty medicine bottle and shouts with glee. On a shelf, a devilish creature stands on two books: Miseries of Human Life, Vol. 2,222 and Buchan’s Domestic Medicine. The man’s fate looks grim as a fat, pompous magistrate leads a procession of mourning women and two evil men, one with a coffin strapped to his back.