English Caricature: Health and the Precariousness of Life

Health issues preoccupied the minds of those living in nineteenth-century England. According to historian Roy Porter, “Health- consciousness ran high in pre-modern England. People rarely ignored their physical well-being till they felt sick: life was too precarious, and medicine too feeble, to permit that luxury.”1 Britons were all too cognizant of the role disease and illness had in shaping or ending their lives. Diseases like typhoid, typhus, cholera, scarlet fever, and influenza could quickly reach epidemic proportions killing tens of thousands of people in a single season. Additionally, nutrition was poorly understood, the rise of industrialization resulted in occupational hazards, and the increase in population in the burgeoning cities led to sewage and waste problems, all contributing to sickness and medical ailments in the populace.2

It was a satirist’s job to provide humorous, and often biting, commentary on all the subjects of the day. Because health issues were so prevalent and Britons were so obsessed with health, the caricaturist found a wealth of material to use in examining disease, illness, medicine, and unorthodox healing methods in nineteenth-century Britain. The general public could easily identify with the medically-related cartoons the satirists produced; who hadn’t felt sick, experienced the side effects of the popular medicines, or grown frustrated with the inefficacy of medical treatments and the high cost of medicine? With wit and cynical observation, the caricaturists elevated health issues to comical proportions, and the laughter their cartoons generated helped allay the public’s anxiety over their physical well-being.

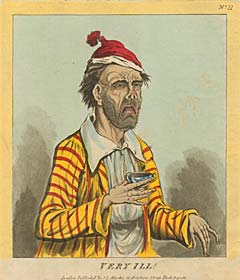

Most Britons could relate to the suffering of the individual in this satire. The artist conveys the ravaging effects of illness by drawing haggard lines and a frown on the character’s face. The man is so sick he remains in his nightclothes, and the stubble on his face indicates that he has been ill for days. His long limp fingers hold a cup of tea that may or may not restore his health.

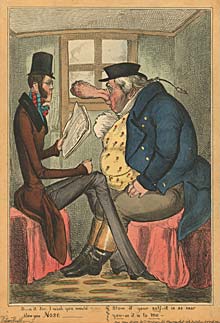

D_n it Sir, I wish you would blow your Nose. William Heath, published by T. McLean, 26 Haymarket, London, May 12, 1830.

A common comedic technique of English caricaturists was to grossly exaggerate facial and physical characteristics, especially the nose and belly. In this 1830 etching, William Heath draws the stomach, and particularly the nose, to comical proportions. The cartoon is a study of two physically opposite characters sitting across from each other in a small, cramped room. The gentleman on the left is long and lean, and possesses a beautifully proportioned face. His antithesis, the person on the right, is short and obese, and sports a huge and grotesque nose. The thin man does his best to read his newspaper, but the other man’s bulbous nose hovering directly over the newspaper, distracts him. The stout fellow evidently has the sniffles causing the thin man to quip, “D_n it Sir—I wish you would blow your Nose.” The rotund character replies with the punch line, “Blow it your self—it is as near you as it is to me.”

A Cure for a Cold: Here’s a go; I must keep my feet in hotwater 20 minutes Take two quarts of gruel wrap my head in flanel and Tallow my nose. Anon, published by G. Tregear, 123 Cheapside, London, 1833.

In this print, the main figure follows popular medical advice to cure himself of a severe cold. The most common medical reference guide found in many Briton’s homes was Domestic Medicine, written by a Scottish physician, William Buchan (1729-1805). Buchan wrote the book in order to, “render the medical art more generally useful, by showing people what is in their own power both with respect to the prevention and cure of diseases.”3 Domestic Medicine, first published in 1769, ran through 142 English editions and was reportedly used in poorer Scottish families until 1927.4

Buchan theorized that colds were the “effect of an obstructed perspiration.”5 The caricature demonstrates the different ways to induce sweating to relieve the symptoms of a cold. First, the man dresses warmly. He wears a huge bulky coat over his nightshirt, ties a scarf around his neck, and wraps his head in flannel. Buchan also suggested, “bathing the feet and legs every night in warm water” to “restore the perspiration.”6 In this print, the man plans on soaking his feet in hot water for 20 minutes. He also stirs a bowlful of gruel. Buchan instructed reducing the quantities of solid food, and instead suggested light bread-pudding, veal or chicken broth, and gruel. He wrote:

His drink may be water-gruel sweetened with a little honey; an infusion of balm, or linseed sharpened with the juice of orange or lemon; a decoction of barley and liquorice with tamarinds, or any other cool, diluting, acid liquor. ABOVE all, his supper should be light; as small posset, or water-gruel sweetened with honey, and a little toasted bread in it. 7

Buchan doesn’t mention rubbing tallow, an animal fat, on the nose. Perhaps tallow was thought to assist the opening of the sinus cavities and provide relief for a stuffy nose.

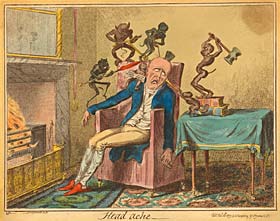

Head Ache. George Cruikshank, published by G. Humphrey, 27 St. James’s St., London, February 12, 1819.

Another common technique of satirists was to blame physical suffering on sinister beings. Goblins, demons, and imps were drawn as energetic creatures that relished inflicting pain on humans. In the 1819 caricature by George Cruikshank entitled “Head ache,” six demons are the root cause of the main character’s misery. The victim’s excruciating headache, perhaps a migraine, has left him weary and lifeless as he sits in a chair in front of a roaring fire. His head hurts so badly that his eyes have rolled back into his head, revealing only the whites of his eyes. With gleeful enthusiasm the devilish characters are working hard at their gruesome task. A demon swings a large mallet to drive a stake into the man’s skull while another drills a terrifying corkscrew device (an enlarged version of a trephine instrument) into his head. In a previously made hole, another demon pours a liquid substance into his brain. Yet another stands on the man’s arm ready to strike with a spear. Cruikshank amusingly captures how noises can further intensify the trials of a headache sufferer by drawing an imp, sitting on the tortured character’s shoulder, obnoxiously singing into one ear while another imp blows a horn directly into the other ear.