“There cannot be a single dissection until a proper theatre is prepared giving an advantageous view of the operation to those within, and effectually excluding observation from without.” Thomas Jefferson, January 11, 1825. [1]

- Robley Dunglison. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

Robley Dunglison and the Anatomical Theatre

Just weeks before Robley Dunglison and his wife arrived in the United States, Thomas Jefferson had written to Joseph C. Cabell, a member of both the University of Virginia Board of Visitors and the Virginia General Assembly, that an anatomical theatre would be “indispensable to the school of Anatomy.” [2] He added, “there cannot be a single dissection until a proper theatre is prepared giving an advantageous view of the operation to those within, and effectually excluding observation from without.” He predicted that its cost would be about the same as one of the hotels which he reckoned at $5,000 or more than $120,000 in 2017 dollars. [3]

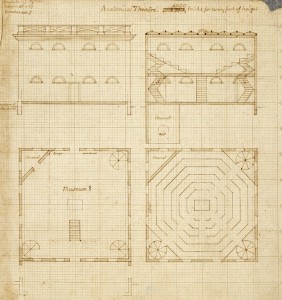

Several days before the first classes at the University in March 1825, the Board of Visitors held a special meeting to address various matters, including the fate of the proposed anatomical theatre which would be used to teach all medical classes, not just anatomy. The Board resolved that once the promised $50,000 from the state government was received, part of the money would be used to build a theatre “as nearly as may be on the plan now exhibited to the board.” [4] Undoubtedly, the plan was Jefferson’s, but with possible input from professional architect Benjamin Latrobe who designed the first anatomical theatre in the United States at the University of Pennsylvania and was instrumental in the design and construction of the Capitol building in Washington D.C. [5] Dunglison wrote in his personal recollections that Jefferson agreed that a building dedicated to anatomical purposes was needed, and that Jefferson would “choose the position and the architectural arrangement externally, whilst all the interior arrangements should be left to me.” [6]

Plan of the Anatomical Theatre by Thomas Jefferson, elevation, two plans and section, ca. 1825. Thomas Jefferson Architectural Drawings for the University of Virginia, circa 1816-1819, Accession #171, Special Collections University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Jefferson’s drawings for the Theatre show a square building measuring 44 feet on each side, with a first floor museum for medical specimens; a second floor octagonal amphitheatre with rising seating; and a charnel, a chamber for bones and dead bodies, in the basement. Access to the charnal is from both the museum and the outside. Circular stairway are placed in three of the four corners from the first floor to the top row of benches on the second floor, and one straight set of stairs rises from the first floor to the center of the second floor. The windows are all lunette shaped, and a skylight goes the length of the roof. The height of the building from the top of the skylights to the bottom of the charnal is also 44 feet.

Procuring Anatomical Preparations

Jefferson might have been willing to leave the interior arrangements to Dr. Dunglison, but he took responsibility for the procurement of specimens himself. March 8, 1825, the day after the first classes were held at the University of Virginia, found Jefferson writing to a gentleman who had earlier paid him a visit at Monticello, Dr. Robert Greenhow of New York, “you mentioned that we could have from Italy the finest anatomical preparations, castings &c and for the cheapest prices of any part of the world. Our University begins its operations this day, and our school of Anatomy and Medicine is as yet unprovided with it’s [sic] proper subjects and apparatus, not possessing even a skeleton to begin with.” [7]

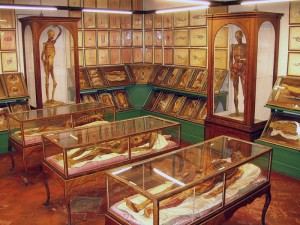

Two weeks later, Jefferson received Dr. Greenhow’s reply that the largest collection of wax anatomical models was to be found in Florence, Italy. Greenhow recommended that Jefferson start with the acquisition of wax models of the ear and the eye for about $80 each. He suggested that skeletons, one male and one female with the bones connected by wire, and one natural skeleton with the bones connected by ligaments, could be obtained from France for under $100. [8] Two skeletons with wire were paid for in May 1825 and their arrival awaited, but the plan to have a third with natural ligaments was abandoned once Greenhow discovered that, “the ligaments of the joints crack when an attempt is made to move them and insects make great havoc.” [9]

Wax Anatomical Models, Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze, Zoologia “La Specola,” Florence, Italy, September 2006. The Museum of Zoology and Natural History, best known as “La Specola” in Florence, Italy, has ten rooms dedicated to anatomic waxes, an art which reached its pinnacle during the 18th century and was used to teach anatomy without cadavers. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/.

Dr. Greenhow also said he could supply Jefferson with anatomical preparations, wet or dry, for very moderate prices from New York. [10] In May 1825, Dr. Dunglison gave Jefferson a list of the preparations he wanted and Jefferson passed on that list to Greenhow. [11] When it turned out that Greenhow could obtain none before winter, and some would not be easily obtained at all because of their rarity, Jefferson and Dunglison decided to order a collection from Europe. [12] It is no wonder Jefferson was eager to obtain items to facilitate the teaching of anatomy; of the 123 students listed as attendees of the first session of classes, 26 registered for the School of Medicine. [13]

By October 1825, $3,000 had been deposited in London to obtain “articles necessary for the Anatomical school” with the expectation that shipments would arrive in the autumn of 1825 and spring of 1826. [14] Apparently, the articles did not come as anticipated which may have been just as well. There was no place to store or display them since construction on the Anatomical Theatre was proceeding slowly. In a letter to Jefferson dated May 21, 1826, Dunglison was clearly frustrated when he wrote, “Cloguet’s [15] & Antomarchi’s [16] plates, in the absence of preparations & Anatomical Theatre would be of the highest value to me.” [17]

- Thomas Jefferson to Joseph Carrington Cabell, 11 January 1825. Founders Online, National Archives. This is an Early Access document retrieved from The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series.

- Thomas Jefferson to Joseph Carrington Cabell, 11 January 1825.

- Thomas Jefferson to Joseph Carrington Cabell, 11 January 1825.

- University of Virginia, Board of Visitors. Minutes, March 4, 1825, 83-84. Retrieved from http://guides.lib.virginia.edu/bovminutes.

- Puzio, Dominic. “The Anatomical Theatre (1825-1939).” JUEL, June 8, 2015. Retrieved from http://juel.iath.virginia.edu/node/242.

- Radbill, Samuel X. (Ed.) The Autobiographical Ana of Robley Dunglison, M.D. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1963, 23.

- Dorsey, John M. (Ed.) The Jefferson-Dunglison Letters. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1960, 17; Thomas Jefferson Papers, 1606 to 1827. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/collections/thomas-jefferson-papers/.

- Dorsey, 18-21.

- Bernard Peyton to Arthur S. Brockenbrough, May 13, 1825. Papers of the Proctor of the University of Virginia, RG-5/3/1.111, Box 5: Folder 482. Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.; Dorsey, 23.

- Dorsey, 21.

- Dorsey, 14-16.

- Dorsey, 28-29.

- University of Virginia. Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia, First Session, March 7, 1825 – December 15, 1825. Charlottesville: Chronicle Steam Book Printing House, 1880, 8.

- University of Virginia, Board of Visitors. Minutes, October 3, 1825, 103-104.

- Jules Cloquet was a professor of clinical surgery and surgical pathology in Paris. He was the author of a large anatomical atlas with five volumes, issued between 1821 and 1831.

- Francois Carlo Antommarchi was a physician and surgeon who served as Napoleon’s doctor on Saint Helena. Prior to that, he was a prosector to the renowned anatomist Paolo Mascagni. From 1823 to 1826, following Mascagni’s death, Antommarchi published Mascagni’s plates under his own name.

- Dorsey, 65-66.

Previous: Thomas Jefferson and the Creation of the University of Virginia

Next: Building the Anatomical Theatre