Resolved: “That the sum of $100 be annually appropriated from the Funds of the University, for the purpose of procuring subjects for the Anatomical class, and for adding to the Anatomical Museum.” July 10, 1832. [1]

The seemingly innocuous word, “subjects,” in the University of Virginia Board of Visitors minutes from 1832 is actually referring to cadavers used for dissection in anatomy classes. In July 1827, when predicting the completion of the space in the Anatomical Theatre to be used for dissections, James Madison had stated, “there is no room for apprehending a want of subjects.” [2] Madison’s assumption was far too optimistic. It would be nearly 60 years before the state legislature passed a law that provided a systematic way for medical schools to obtain bodies for dissection. Until then, most cadavers were obtained by body snatching from graves or requesting in advance the bodies of criminals condemned to death. The responsibility for these acquisitions, if not the actual task, fell to anatomy demonstrators and professors and sometimes their students.

Documents from 1834 and 1835 give some sense of the difficulties of obtaining bodies. Minutes from the Journals of the Chairman of the Faculty relate that Dr. Augustus Warner, who taught anatomy and surgery at the University of Virginia for several years in the mid-1830s, was not pleased with subjects sent from Baltimore. On several occasions, having located bodies nearby, he and some of his students asked to use the University’s cart and horse for transportation purposes. This resulted in a heated exchange between two administrators, the Chairman of the Faculty and the Proctor, about the propriety and the practicality of such a use. Permission was eventually granted, but only after the Chairman directed a janitor to “break open the door [to the stable], taking care, whilst so doing to commit the least possible injury to the property.” [3] Warner’s frustration with the difficulty of obtaining subjects in Charlottesville was an impetus for him to relocate in Richmond where he and five colleagues, in conjunction with Hampden-Sydney College opened a medical school which eventually became the Medical College of Virginia. [4]

At least one excursion in 1834 ended violently when a student “was shot in the back by an old fellow while endeavoring to take a dead negro for our anatomical dissections.” The student, A.F.E. Robertson, recovered and graduated from the school of medicine in 1835 while the “old fellow,” Mr. Oldham, was not prosecuted. One of Robertson’s fellow students, Charles Ellis reported in his diary that some lawyers thought it was most unusual for Oldham to not be brought to trial. Ellis believed it resulted from ill will between students and the county people who “imagine us cannibals, or something worse, who can take up the bodies of dead persons, and cut them to pieces.” [5]

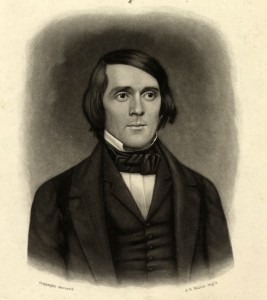

John Staige Davis, Professor of Anatomy, Materia Medica, Therapeutics, and Botany by Adam B. Walter, circa 1859. Prints10069, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Much of what is known about the process of obtaining cadavers for teaching anatomy at the University after the 1830s is due to Dr. John Staige Davis. Dr. Davis earned his medical degree from the University of Virginia in 1841 when he was only 16 years old. He would have paid the “trifling cost of $5″ for the purpose of procuring subjects for the study of practical anatomy. [6] After graduation he received his clinical training in Philadelphia and then set up a medical practice in Jefferson County, Virginia. He returned to the University to become demonstrator of anatomy for the 1847-1848 session, which happened to be the same time frame that the Virginia General Assembly made disinterment of a dead body a felony. [7] He was determined to have his students learn by individual dissection, rather than just by watching a demonstrator, but that required quite a lot of cadavers — more than 25 a session by 1860. [8]

Dr. Davis sought the help of intermediary agents in Richmond, Norfolk, and Alexandria, Virginia, who made arrangements with men called body snatchers or resurrectionists to take cadavers from “the cemeteries of the sizable slave, free black, and poor white populations of Virginia’s leading urban centers,” pack them in bran or sawdust in large whiskey or oil barrels, and then transport the barrels by train from the Richmond-Petersburg area. [9] Davis made copies of his correspondence with his agents, who often had an association with the University of Virginia or the Medical College of Virginia, originally the Medical Department of Hampden-Sydney College, in Richmond. He also saved letters that were written to him, in spite of at least one correspondent pleading with him to do otherwise. Dr. Lewis W. Minor wrote, “After taking such notes from my letters as you may think desirable, I pray you to destroy them for truly they have not even a respectable appearance.” [10] These letters are now housed in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia. They give a fascinating glimpse into the role of an anatomy professor in the middle of the 19th century and the difficulties and complexities of obtaining bodies for dissection. Some of these troubles are illustrated below by Davis’s correspondence, prefaced by questions that might have been asked by an anatomist responsible for teaching medical students in the years prior to a legal and standardized way of procuring cadavers.

The Difficulties of Body Snatching

How do you find someone you can trust, but who is willing to commit a felony to disinter bodies?

—“The difficulty is that in applying to persons, and especially to those whose disposition I do not know, they would get into the secret whether they accepted the place or not,” and, “There are men here in any quantity who would engage in such a trade, but they are such characters as cannot be relied upon.” H.L. Thomas [11]How do you get the bodies out of Richmond when the medical school there is competing for them, too?

—“He [the resurrectionist] says the faculty here have sworn that no subject shall be carried from Richmond this winter.” H.L. Thomas [12]How do you deal with the vagaries of weather, too hot or too cold?

—“He [the resurrectionist] says the weather having been so warm here that the subjects are all in incipient putrefaction when buried, … I have reconnoitered the grounds myself, and the only colored burial I have noticed, the coffin was already sprung, from the decomposition.” H.L. Thomas [13] —“Had it not been for the extremely cold winter the agent here would have furnished as many subjects as you might have wanted.” T.C. Brown [14]What if there is a shortage of deaths?

—“Richmond is so distressingly healthy at this time.” H.L. Thomas [15]Or what if there are too many deaths?

—“The late comers [Davis is referring to bodies] have subjected us to extreme inconvenience – the Dissecting Room being previously crowded – indeed, several of the subjects are still unpacked … stop, until further notice.” John Staige Davis [16]What happens if a barrel goes astray and is opened as apparently happened in November 1850?

—“The papers this morning state that the barrel (whisky) was addressed to – ‘McIntire Charlottesville’ – Of course all barrels boxes &c large enough to contain your favorite article of trade, and addressed as above, will in future be closely scrutinized.” Lewis W. Minor [17] —An article in The Alumni Bulletin recalls “Miss Betty” who made the “mistake of opening a barrel that was intended for the anatomical hall, instead of the barrel of sweet potatoes she expected from Isle of Wight county.” Charles Christian Wertenbaker [18]How to get acceptable bodies, not ones that are “fat” or “dropsical” without casting suspicion by questioning about the deceased’s body type?

—“The suggestion made with regard to the ‘physique’ of the bodies you need is good; if it could only be followed. On reflection however, you will find that to make the antecedent enquiries refered [sic] to, would, at any time, be far from easy, or safe.” A.E. Peticolas [19]What if your resurrectionist is arrested or is no longer interested?

—The anatomy professor at the Medical College of Virginia, who was Dr. Davis’ contact in Richmond, wrote, “to continue my lectures I was forced to play resurrectionist myself; by no means a pleasant profession, when the snow is 8 inches deep and the thermometer near zero.” A.E. Peticolas [20]

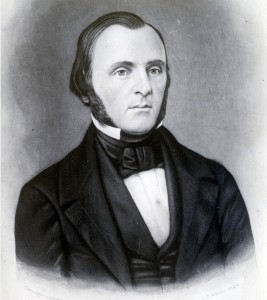

James Lawrence Cabell, Professor of Anatomy, Comparative Anatomy, Physiology, and Surgery by Adam B. Walter, circa 1859. Prints16145, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

The Davis correspondence includes a letter from Dr. James L. Cabell who followed Dr. Warner as the anatomy and surgery professor at the University in 1837. Cabell remained the sole instructor in anatomy until Dr. Davis arrived in 1847 to be the anatomy demonstrator. Two sessions later in 1849, Davis was both lecturer and demonstrator in anatomy while Cabell taught comparative anatomy, undoubtedly relieved to give up the business of procuring cadavers. In 1851, while encouraging Davis to enter into a body sharing agreement with the Richmond medical school, he writes, “You, even you, can have but a faint conception of the extreme difficulty I had for a series of years prior to Carter’s appointment as Demonstrator, in processing a very moderate supply for a class of only forty or fifty students at the enormous price of thirty dollars a barrel.” [21] Dr. Cabell is referring to Carter P. Johnson who was the demonstrator of anatomy from 1844 to May 1848 and professor of anatomy from May 1848 to September 1854 at the Medical Department of Hampden-Sydney College in Richmond. Johnson was instrumental in devising a plan to share subjects between the two schools in Charlottesville and Richmond with the greater share staying in Richmond. [22]

Requests for Bodies of Executed Criminals

Several letters in the Davis collection relating to anatomical dissection do not concern the removal of bodies from graves, but to another means of procurement — using the bodies of executed criminals. In 1779, Thomas Jefferson had proposed a bill to the Virginia General Assembly concerning crimes and punishments where he advocated that those convicted of petty treason or the murder of certain family members be hung and their bodies delivered to anatomists for dissection. [23] Not only did Jefferson’s bill fail, but another act that same year prohibited the dissection of executed murderers. [24] However, this did not prevent students or Professor Davis from pursuing this potential source.

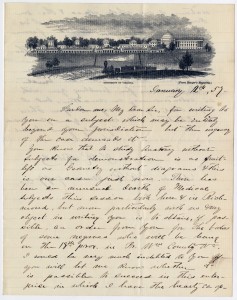

T.R. Roberts who claimed to be a student at the University of Virginia wrote to Governor Henry A. Wise. Roberts was anticipating the hanging of enslaved persons for killing their owner, George Green, on Christmas Eve, 1856: [25]

January 12th, 57-

Pardon me, My Dear Sir, for writing to

you on a subject which may be entirely

beyond your jurisdiction but the urgency

of the case demands it.

You know that to study Anatomy without

Subjects for demonstration is as fruit-

less as Geometry without diagrams & this

is our case just now. There has

been an unusual dearth of Medical

Subjects this session both here & in Rich-

mond, but more particularly with us & my

object in writing you is to obtain, if pos-

sible, an order from you for the bodies

of some negroes who will be hung

on the 18th prox. in Pr. Wm County Va.

I would be very much indebted to you if

you will let me know whether it

is possible to succeed in this enter-

prise in which I have the hearty co-op-

eration of our whole class & tho’ our

Professors are not aware of it, I’ve

no doubt they too would favour

our request.

If we obtain your permission the

bodies will be brought either by a

committee of Medical Students or

some one whom we can trust.

Pardon me for troubling you with

so extraordinary a matter, but I

hope that your regard for this

institution will ensure your permission

Very truly your obedient

Servant-

T.R. Roberts.

Address T.R.R. University of Va [26]

T.R. Roberts to Henry A. Wise, January 12, 1857, page 1. Governor Henry A. Wise Executive Papers, 1856-1859, Box 6: Folder 2. Accession #36710, January 14, 1857, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

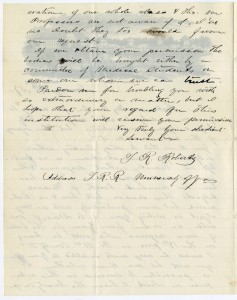

T.R. Roberts to Henry A. Wise, January 12, 1857, page 2. Governor Henry A. Wise Executive Papers, 1856-1859, Box 6: Folder 2. Accession #36710, January 14, 1857, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Whether Mr. Roberts was successful or not in his attempt to obtain the bodies of the enslaved prisoners after their hanging is unknown, but nearly three years later, Professor Davis himself asked for the bodies of “Convicts awaiting execution.” These convicts were in Charles Town which is in Jefferson County, where Davis had a medical practice during the 1840s. Not referring to common criminals, Davis was requesting the bodies of the men scheduled for hanging as a result of their participation in the raid by abolitionist John Brown at the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, seven miles east of Charles Town. No answer regarding this request is in the Davis letters, but it is clear that multiple bodies ended up at Winchester Medical College, 20 miles from the site of execution. Davis probably felt this was a loss for the University of Virginia, but it may have worked to the University’s benefit as the Winchester medical school was burned in 1862 by Union troops, purportedly because the body of John Brown’s son was used for dissection and his skeleton placed in the College’s anatomical museum. [27]

University. Dec: 8th 1859

C.C. Wertenbaker Esq

Dear Sir,

Dr. Cabell has

handed me a letter just received from you, in relation, to

the Convicts awaiting execution, & to the chance of procuring one

or more of their bodies for dissection in my department -

Apart from the expense of sending two or three members

of my class to Charlestown, such a step would expose me to

the animadversion of their parents – If however, you can

contrive to get them, the box in which they are packed

might come on the cars when you return, & I will

very thankfully reimburse the charges you incur-

Respectfully yours,

J.S. Davis. [28]

The Virginia Anatomical Act

It was not until 1884 that the Virginia Anatomical Act, having the dual purpose of promoting medical science and protecting graves and cemeteries from desecration, was passed to regulate the disposal of unclaimed bodies to be buried at public expense. This opened the way for many bodies to be used legally for the purpose of anatomical study. [29] Dr. Davis must have been relieved with the passing of this Act as a year earlier, more than 40 years after he started teaching anatomy, he was still trying to obtain cadavers for teaching. In response to another physician who was asking for a set of bones, he made his own request, “We were never so much in need of subjects as now. Is any body to be hung in Henry, whose corpse I might procure -” [30]

Dissecting Club, 1906-1907. First and second year students studied anatomy in 1907, a year which saw 74 students in those two classes combined. Theodore Hough in the front row, center, was the Professor of Physiology. Prints21241, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

The 1896-1897 Catalogue states that practical anatomy, taught in the Dissecting Hall, used “dissecting material, obtained under the permissive law of the State … abundantly supplied without cost to the student.” It also mentions dissecting clubs of eight men each with no more than five clubs admitted to the Hall at one time. [31] The image to the left is titled “Dissecting Club” and was taken by Holsinger’s Studio, the leading photography studio in Charlottesville. Perhaps it is a formal portrait of two clubs combined. Other photos from 1893 to 1909 are in the University of Virginia Visual History Collection and capture University of Virginia students (and faculty) in macabre poses with their cadavers.

Sources- University of Virginia, Board of Visitors. Minutes, July 10, 1832, 75, Retrieved from http://guides.lib.virginia.edu/bovminutes.

- University of Virginia, Board of Visitors. Reports of the Board of Visitors to the Literary Fund 1814-1837, 1827: 24. RG-1/1/6. 151, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- Journals of the Chairman of the Faculty 1827-1864, November 15, 1834 and January 14, 1835, Box 2: Volume 5. RG-19/1/2.041, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- Koste, Jodi L. “Artifacts and Commingled Skeletal Remains from a Well on the Medical College of Virginia Campus: Anatomical and Surgical Training in Nineteenth-Century Richmond.” VCU Scholars Compass (June 18 2012): 5. Retrieved from VCU Scholars Compass.

- Archibald Cary to Septimia Randolph, December 15, 1834. Randolph-Meikleham Family Papers, 1792-1882, Box 1: Folder 59. Accession #4726-a, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.; Head, Ronald B. (Ed.). “The Student Diary of Charles Ellis, Jr., March 10-June 25, 1835,” The Magazine of Albemarle County History 35 and 36 (1977-1978): 59.

- University of Virginia. Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia, Session of 1842-43. Richmond: Shepherd and Colin, 1843, 22.

- Breeden, James O. “Body Snatchers and Anatomy Professors: Medical Education in Nineteenth-Century Virginia.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 83:3 (July 1975): 326, 327; University of Virginia. Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia, Session of 1847-48. Richmond: H.K. Ellyson, Printer, 1848, [3]; Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia: Passed at the Session Commencing December 6, 1847, and ending April 5, 1848. Richmond: Samuel Shepherd, Printer to Commonwealth, 1848, 112.

- Breeden, 327.

- Breeden, 328.

- Lewis W. Minor to John Staige Davis, November 30, 1850. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1850-1855. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- H.L. Thomas to John Staige Davis, September 5, 1849 and September 12, 1849. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1846-1849. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- H.L. Thomas to John Staige Davis, September 12, 1849. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1846-1849. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- H.L. Thomas to John Staige Davis, November 3, 1849. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1846-1849. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- T.C. Brown to John Staige Davis, March 5, 1857. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1856-1859. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- H.L. Thomas to John Staige Davis, November 3, 1849. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1846-1849. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- John Staige Davis to A.E. Peticolas, February 8, 1859. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 3: Letterpress book. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- Lewis W. Minor to John Staige Davis, November 15, 1850. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1850-1855. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- Wertenbaker, Charles Christian. “Early Days of the University.” The Alumni Bulletin 4:1 (May 1897): 24.

- A.E. Peticolas to John Staige Davis, January 26, 1852. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1850-1855. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- A.E. Peticolas to John Staige Davis, January 26, 1852. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1850-1855. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.; A.E. Peticolas to John Staige Davis, January 21, 1856. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1856-1859. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- James L. Cabell to John Staige Davis, July 23, 1851. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 1: Folder 1850-1855. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- Koste, Jodi L. “Artifacts and Commingled Skeletal Remains from a Well on the Medical College of Virginia Campus: Anatomical and Surgical Training in Nineteenth-Century Richmond.” VCU Scholars Compass (June 18 2012): 9. Retrieved from VCU Scholars Compass.

- The relevant paragraph in Jefferson’s Bill for Portportioning Crimes and Punishments in Cases Heretofore Capital is, “If any person commit Petty treason, or a husband murder his wife, a parent his child, or a child his parent, he shall suffer death by hanging, and his body be delivered to Anatomists to be dissected.” Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 2, 1777 – 18 June 1779. Edited by Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950, 494.

- Hartwell, Edward Mussey. “The Hindrances to Anatomical Study in the United States, Including a Special Record of the Struggles of Our Early Anatomical Teachers.” Annals of Anatomy and Surgery 3 (January-June 1881): 218. Retrieved from HathiTrust Digital Library.

- See “The Killing of George Green by his Slaves December 1856” and following documents at http://www.pwcvirginia.com/RonsRamblings.htm. Prince William County Virginia, African American and Slave Records by Ronald Ray Turner.

- T.R. Roberts to Henry A. Wise, January 12, 1857. Governor Henry A. Wise Executive Papers, 1856-1859, Box 6: Folder 2. Accession #36710, January 14, 1857, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

- Cook, Abner H. “The Winchester Medical College, Winchester, Virginia, 1827-1862.” The Medical Pickwick 4:1 (January 1918): 3-7. Retrieved from HathiTrust Digital Library; Duncan, Richard R. Beleaguered Winchester: A Virginia Community at War, 1861-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007, 58.

- John Staige Davis to C.C. Wertenbaker, December 8, 1859. Papers of John Staige Davis, 1840-1888, Box 3: Letterpress book. MSS 1912, 2842, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- Virginia. Acts and Joint Resolutions Passed by the General Assembly of the State of Virginia during the Session of 1883-84. Richmond: R.U. Derr, 1884, 61-62, 816. Retrieved from HathiTrust Digital Library.

- John Staige Davis to S.G. Pedigo, January, 9, 1883. MSS 2029, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

- University of Virginia. Catalogue, 1896-1897, Announcements 1897-1898. (n.p.), 108.

Previous: Building the Anatomical Theatre

Next: The Pre-Civil War Anatomical Theatre