Early Research and Treatment of Tuberculosis in the 19th Century

Early Research: Jean-Antoine Villemin and Robert Koch

Early Treatment: Edward Livingston Trudeau and the Sanatorium

Cartoon by Fred O. Seibel

The American Lung Association is dedicated to the cure and control of all lung diseases, but its formation in 1904 was in response to only one: tuberculosis. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, tuberculosis (TB) was the leading cause of death in the United States, and one of the most feared diseases in the world.

Formerly called “consumption,” tuberculosis is characterized externally by fatigue, night sweats, and a general “wasting away” of the victim. Typically but not exclusively a disease of the lungs, TB is also marked by a persistent coughing-up of thick white phlegm, sometimes blood.

Cartoon by Fred O. Seibel

There was no reliable treatment for tuberculosis. Some physicians prescribed bleedings and purgings, but most often, doctors simply advised their patients to rest, eat well, and exercise outdoors.[1] Very few recovered. Those who survived their first bout with the disease were haunted by severe recurrences that destroyed any hope for an active life.

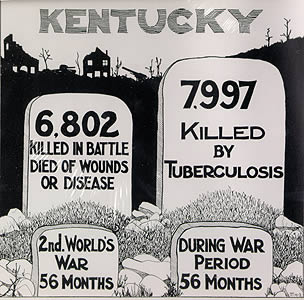

Kentucky TB Association Ad, ca. 1945

It was estimated that, at the turn of the century, 450 Americans died of tuberculosis every day, most between ages 15 and 44.[2] The disease was so common and so terrible that it was often equated with death itself.

Tuberculosis was primarily a disease of the city, where crowded and often filthy living conditions provided an ideal environment for the spread of the disease. The urban poor represented the vast majority of TB victims.

Villemin, Koch & Contagion

Jean-Antoine Villemin (1827-1892)

Science took its first real step toward the control of tuberculosis in 1868, when Frenchman Jean-Antoine Villemin proved that TB was in fact contagious. Before Villemin, many scientists believed that tuberculosis was hereditary. In fact, some stubbornly held on to this belief even after Villemin published his results.[3]

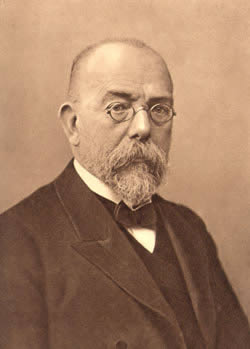

Robert Koch (1843-1910)

In 1882, German microbiologist Robert Koch converted most of the remaining skeptics when he isolated the causative agent of the disease, a rod-shaped bacterium now called Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or simply, the tubercle bacillus.

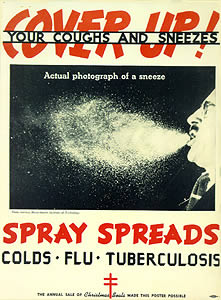

The work of Villemin and Koch did not immediately lead to a cure, but their discoveries helped revolutionize the popular view of the disease. They had demonstrated that the tubercle bacillus was present in the victim’s sputum. A single cough or sneeze might contain hundreds of bacilli. The message seemed clear: stay away from people with tuberculosis.

Cover Up!

This new rule of behavior was sensible, but it made the tubercular invalid an “untouchable,” a complete outcast. Many lost their jobs because of the panic they created among co-workers. Many landlords refused to house them. Hotel proprietors, forced to consider the safety of other guests, turned them away.[4] Rejected by society, tuberculosis victims gathered in secluded tuberculosis hospitals to die.

Trudeau & the Sanatorium

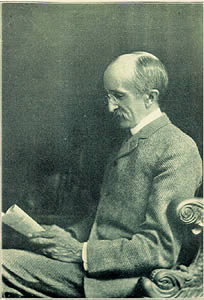

Edward Livingston Trudeau (1848-1915)

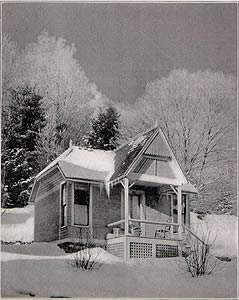

Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau (1848-1915) was the first American to promote isolation as a means not only to spare the healthy, but to heal the sick. Trudeau believed that a period of rest and moderate exercise in the cool, fresh air of the mountains was a cure for tuberculosis. In 1885, he opened the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium (often called “the Little Red Cottage”) at Saranac Lake, New York, the first rest home for tuberculosis patients in the United States.

“The Little Red Cottage” at Saranac Lake, NY. Image from An Autobiography by Edward Livingston Trudeau, 1916.

Dr. Trudeau’s sanatorium plan was based on personal experience. When he was nineteen, Trudeau watched his older brother die of TB, an experience that convinced him to become a physician. In 1872, just a year after leaving medical school, he, too, contracted tuberculosis. Faced with what he believed to be a sure and speedy death, Trudeau left his medical practice in New York City and set off for his favorite resort in the Adirondacks to die.[5] There, instead of wasting away, he steadily regained his strength, due entirely, he believed, to healthy diet and outdoor exercise. Experiments on tubercular rabbits in his lab at the cottage seemed to verify his belief. In February of 1885, Trudeau welcomed the first group of hopeful patients to his sanatorium in the woods.

Child Memorial Infirmary with open-air porches for tuberculosis patients at Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium, Saranac Lake, N.Y. Library of Congress.

Trudeau required his guests to follow a strict regimen of diet and exercise. They were given three meals every day, and a glass of milk every four hours. Trudeau and his staff encouraged their patients to spend as much time as possible outdoors. At first, this meant extended periods of sitting on the sanatorium veranda (the open-air porch was a standard feature of Trudeau-style sanatoriums). Gradually, patients spent more time walking than sitting, until they were able to spend 8 to 10 hours per day exercising outdoors, regardless of weather.[6] Trudeau made his rest home available to the poor by setting a very low rent and providing free medical service. By 1900, what started as a single red cottage was a small village, a 22-building complex that included a library, a chapel, and an infirmary.

Sources

- Edward O. Otis, The Great White Plague (New York: Crowell & Co., 1909), 100-103.

- Sheila M. Rothman, Living in the Shadow of Death: Tuberculosis and the Social Experience of Illness in American History (New York: BasicBooks, 1994), 190; Richard H. Shryock, National Tuberculosis Association, 1904-1954: A Study of the Voluntary Health Movement in the United States (New York: NTA, 1957), 63.

- Shryock, 6.

- Otis, 44-45.

- Mark Caldwell, The Last Crusade: The War on Consumption, 1862-1954 (New York: Atheneum, 1988), 42-43.

- Rothman, 203-204.