American Lung Association Anti-Spitting Campaign and Modern Health Crusade

Fighting Tuberculosis by Health Education

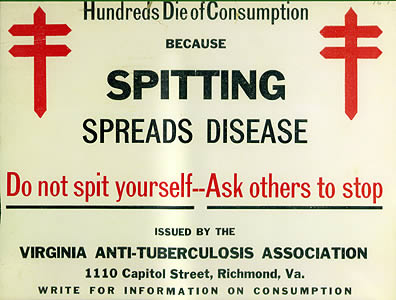

The building and maintenance of sanatoriums was only one part of the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis (NASPT) mission. As a result of Jean Antoine Villemin and Robert Koch discovering tubercle bacilli in sputum, the NASPT and its state affiliates campaigned aggressively against public spitting. In his book, The Great White Plague, Dr. Edward Otis, President of the Boston Tuberculosis Association, printed a list of nineteen rules for children that highlights the anti-spitting campaign:

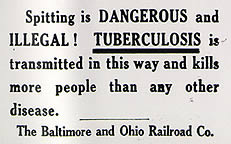

B&O Railroad anti-spitting card, 1917

1. Do not spit.

2. Do not let others spit.

3. If you have a cough, and must spit, use a paper napkin or a piece of newspaper, and put it in the stove.

… 19. And last as well as first, DO NOT SPIT.[1]

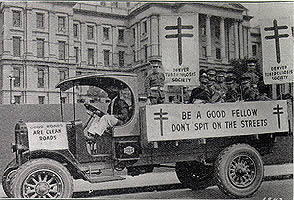

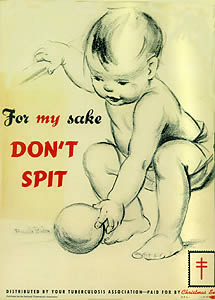

The amazing fact that tubercle bacilli could survive in spit for an entire day convinced many ladies to stop wearing their long, trailing dresses into town for fear they might pick up sputum and drag tuberculosis into their homes.[2] Many communities outlawed spitting in the streets and on the floors of shops, theaters, and taverns and required managers of public gathering spots to have spittoons available for their guests. Newspapers, street signs and bulletin boards carried warnings against “the filthy habit:”

Denver Anti-Spitting Campaign, ca. 1920

BEWARE OF THE CARELESS SPITTER

DON’T SPIT, SAVE LIVES

WHO LOVES A SPITTER?

MEN! IT’s UP TO US! SPITTING SPREADS DISEASE–AND WOMEN DON’T SPIT!

PROTECT THE CHILDREN, DON’T SPIT

NTA anti-spitting notice, 1943

Though everyone was expected to follow the new spitting rules, people with tuberculosis were more carefully monitored than anyone else. Spittoons used by “lungers” were immediately disinfected with carbolic acid or boiling water; their handkerchiefs and napkins were placed in designated containers and burned.[3]

The Modern Health Crusade

Crusaders in Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1915

In 1915, the NASPT launched the Modern Health Crusade, originally to involve children in the Christmas Seal Campaign. Any child who sold ten or more Seals was given a “Crusader certificate of enrollment” on which was printed a list of health rules such as “keep windows open” and “get a long night’s sleep.” The Crusade quickly grew into a new health education system for elementary schools.

Crusaders in Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1915

Crusade directors sought to arouse children’s interest in health by introducing elements of play, chivalry, and competition into the study and practice of hygiene. The program was based on eleven tasks:

Christmas, 1956.

Crusader Christmas Seal play, 1956.

1. I washed my hands before each meal today.

2. I washed not only my face, but my ears and neck, and I cleaned my finger-nails today.

3. I kept fingers, pencils, and everything likely to be unclean or injurious out of my mouth and nose today.

4. I brushed my teeth thoroughly after breakfast and after the evening meal today. I took ten or more slow, deep breaths of fresh air today. I was careful to protect others if I spit, coughed, or sneezed.

5. I played outdoors or with open windows more than thirty minutes today.

6. I was in bed ten hours or more last night and kept my windows open.

7. I drank four glasses of water, including a drink before each meal, and drank no tea, coffee, or other injurious drinks today.

8. I tried to eat only wholesome food and to eat slowly.

9. I went to toilet at my regular time.

10. I tried hard today to sit up and stand up straight; to keep neat, cheerful, and clean-minded; and to be helpful to others.

11. I took a full bath on each of the days of the week that are checked.

Children who complied with these standards were “promoted” from squire to knight, then to knight banneret, and finally to knight of the round table. By 1919 there were three million “crusaders” in the United States. Two years later, the National Education Association recommended the adoption of a Crusade-like health education system in every elementary school in the country.

Crusaders’ Song by Emily Nichols Hatch, ca.1920s

Hail! all ye gentle knights and squires and pages!

Crusaders’ band, for health we stand.

While all around life’s battle fiercely rages

We’ll do our part — clean hands and heart.

Our soldiers bravely there in France were fighting

Like knights of old, chivalrous, bold.

Like them we must some wrong each day be righting

With smiles of cheer, and know no fear.With souls and bodies growing strong and stronger

Brave Knights we’ll be, our land to free.

From curse of dread disease which shall no longer

O’er it prevail, we shall not fail.

The holy war which we must still be waging

Is for good health, tis more than wealth.

The health of mind and body both engaging

Our efforts true in all we do.Chorus

We’ll battle, we’ll conquer; disease and dirt we’ll slay!

We’ll scout them and rout them and drive them off each day!

With hands and bodies clean and hearts all brave and bold.

Prepared our country’s flag and honor to uphold.

Sources

[1] Edward O. Otis, The Great White Plague (New York: Crowell & Co., 1909), 245-47.

[2] Lawrence F. Flick, Consumption, a Curable and Preventable Disease, (Philadelphia: Flick, 1904), 172, 257.

[3] Flick, 254-56, 266-71.

[4] S. Adolphus Knopf, A History of the National Tuberculosis Association: The Anti-Tuberculosis Movement in the United States (New York: NTA, 1922), 43-44.

[5] Richard H. Shryock, National Tuberculosis Association, 1904-1954: A Study of the Voluntary Health Movement in the United States (New York: NTA, 1957), 170-73.