War in Italy

Supporting the Fifth Army from Caserta to Pietramala

The 8th Evac Starts Work in Italy

Litter Bearers Re-Enactment

In October 1943 the 8th Evacuation Hospital moved past crashed planes, burned tanks, and destroyed buildings to Caserta, Italy, to finally begin receiving non-operative patients in buildings on the grounds of a huge castle. Hepatitis, malaria, respiratory infections, psychoneurosis, and psychosis were the most common diseases. Trench foot, shrapnel wounds, fractures, and sprains were the most common diagnoses made on the surgical service.

Lieutenant Colonel Harris Holmboe

Enlisted Men in the Utilities Tent

Lieutenant Colonel Harris Holmboe, Assistant Resident in Surgery at the University of Virginia, was largely responsible for re-equipping the Hospital during the time in Caserta and improving its ability to function. He set up a hospital workshop and worked closely with Randal Luscombe to design equipment over the course of the war. Surgical tents were normally supported with center-poles which hampered movement and slowed the surgeons. A method of erecting the tents without the awkward center-pole was devised. Holmboe obtained aluminum from German bomb cases to make sinks, improved the standard water-heating system, was involved in designing an adjustable operating table and, in general, used his ingenuity to make life in the field more efficient and less onerous.

Wounded around Receiving Room Stove

In December 1943 the Hospital continued its northwest movement in Italy to an area near Teano, where it first functioned as a field hospital as part of a combat operation. The Hospital served an area where some of the most intense fighting of the war occurred under difficult conditions. The locale was mountainous, and rain, snow, and sleet resulted in ankle deep mud which hampered the transportation of daily necessities to the troops on the front and the evacuation of the wounded.

Patient Care in Italy

Casualties in Receiving Tent

Surgical Tent

Dental Clinic

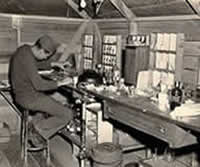

Clinical Lab

Soldiers injured in battle generally made several stops before arriving at the 8th Evacuation Hospital. Medics or aidmen sent the wounded to a battalion aid station at the rear for a quick assessment. From the aid station an ambulance carried the injured to a small hospital for triage. Wounded considered unable to endure another ambulance ride to an evacuation hospital, such as those in shock or with severe wounds, were cared for at this location and transferred later to the evacuation hospital. Those judged able to tolerate another ambulance ride were sent to the evacuation hospital for treatment.

Upon arrival at the 8th Evacuation Hospital, the soldiers were sorted in the receiving section. Surgical patients were sent to the surgical wards if they did not need immediate operations. Those with serious wounds or injuries went to one of the three shock wards which could handle one hundred patients at a time as they waited for surgery. Patients with disease went to the medical wards.

The primary function of the 8th Evacuation Hospital was care of the wounded, but nearly two-thirds of the admissions during the three months near Teano were due to disease. The Hospital had wards devoted to: neuropsychiatric disease; one for orthopedic operations; another for diseases of the eyes, ears, nose and throat; and dental clinics where thousands of outpatients were seen.

The Spring-Summer 1944 Offensive

Ambulances lined up to evacuate patients to base hospitals

Tent Pitching: The unit became experts in pitching tents.

Medicinal Packing: The new system packing is demonstrated.

Reshuffling allied troops prior to a spring offensive resulted in a move for the 8th Evacuation Hospital in late March 1944 from Teano to Carinola. Six weeks of relative quiet and the replacement of Colonel McKoan by Lieutenant Colonel Drash as acting commanding officer were followed by an Allied artillery barrage on May 11th. In a little over an hour the wounded began to arrive at the Hospital, which had prepared for the assault by sending as many patients as possible to base hospitals by ambulances and fully stocking the blood bank.

The progress of the Allied offensive can be seen by the rapidity with which the 8th Evacuation Hospital moved in Italy. On May 21, 1944, the unit moved from Carinola and by August 31st had functioned in Cellole, Le Ferriere, Grosseto, Cecina, and Galluzzo. The unit was extremely efficient in moving. Upon leaving Cellole it packed and took down the 750-bed hospital, transported it 80 miles, and had it ready to accept patients within thirty hours.

The movement of the front meant that a hospital only a few miles from the fighting could soon be sixty miles in the rear as other hospital units leapfrogged to the battle zone. The percentage of admissions due to battle casualties was directly related to how close the unit was to fighting. Those units further to the rear admitted more patients for disease. In Grosseto, for the first time, the Hospital had more admissions for wounds than disease. When the 8th Evacuation Hospital was close to the front, it could have eight operating teams working in surgery, assisted by medical and dental officers.

Colonel Lewis W. Kirkman

Galluzzo, six miles from Florence, was reached by the 8th Evacuation Hospital on August 30, 1944, under the command of Colonel Lewis W. Kirkman, a graduate of the Northwestern University School of Medicine. September was a busy month with an average of one thousand cases a week, fifty operations a day, and sometimes three hundred admissions and discharges in a day. Rainy weather, mountainous surroundings, and insufficent roads added to the heavy load of all medical units.

Preparing for Winter in Pietramala

Mud in Pietramala

Winterized Ward Tent

Winterized Tent: An oil burning stove heats a winterized tent with wooden floor and sidewalls.

Chopping Wood: The Army provided no fuel for personnel living quarters so the unit improvised.

Prefabricated Shock Ward

The Allied advance slowed in the fall because of the difficulty of fighting in the mountains in northern Italy and the torrential rains which made roads nearly impassable. In October 1944, the 8th Evacuation Hospital moved to a muddy field at Pietramala north of Florence and stayed for six months. During that time, five thousand truckloads of rock were deposited to make the muddy field and nearby roads passable.

Early in the stay rain and fog were common, but in November the rain turned to snow and the temperature dropped to below freezing much of the time. The ground was covered with snow nearly continuously from December to March, and the staff became accustomed to wearing long woolen underwear, woolen uniforms, and multiple pairs of socks in an attempt to keep warm.

The decision was made to keep the unit in the mountains over the winter, and the process of winterizing the tents began. Engineers and hospital personnel built wooden floors and sidewalls for ward tents and personnel tents. Roof bracing was added to ensure that the canvas tops would not collapse from accumulated snow.

Prefabricated buildings were used as shock wards, regular wards, and for various auxiliary buildings. Extra bracing and anchoring was added due to the high winds in the mountains. Once the foundation was laid, thirty men could complete a building in under two days. Winterizing a ward tent took twelve men a similar amount of time. The winterizing process was completed in early December.